The Labor Movement and Maureen Brady’s Folly

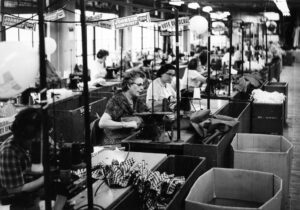

Maureen Brady’s 1982 novel, Folly, is an expansive love story that begins when a diverse group of women decide to walk off their garment factory jobs. Set in the fictional, working-class town of Victory, North Carolina, in the armpit of the 1970s, Folly gets right what the 1979 film Norma Rae gets wrong about the portrayal of female labor movements: that the heroes of collective struggle are manifold.

The novel’s walkout is impromptu; word spreads around the busy jeans factory that a woman, leaving her sick child alone to work the night shift, has been arrested for negligence when the child dies. With no sick leave, the women at the factory fear they will be replaced should they not show up for their shifts. This, paired with the escalating quota expectations and poor treatment by the boss, whom they refer to as Fartblossom, leads to a tense confrontation between him and the book’s namesake, Folly. When Fartblossom doesn’t show concern for the women’s demands, others begin to speak up until “the concentration which centered on Folly, fluttering in the breast of each woman there, pulsed almost audibly […] Every woman could feel the others’ feelings.” In a wordless moment, they all decide to walk out together.

Across the country, labor organizers in the 1970s, looking back at the successes of the 1930s, were desperate to maintain the tenuous grasp they had over production, and the rights that grasp afforded rank and file workers. An increasingly female and diverse labor force also found conflicts and alliances through labor activism. In 1974, a largely female, Hispanic workforce went on strike for two brutal years at the Farah pants factory in El Paso, Texas, and Norma Rae’s inspiration, Crystal Lee Sutton, was embroiled in one of the bitterest organizing attempts in the United States’s already bloody labor history. The same year, labor activist Karen Silkwood, while trying to expose health and safety violations at the Oklahoma nuclear facility where she worked, was killed in a mysterious car accident. As the working class fought to maintain and improve upon their hard won labor rights, economic liberalization and imperialism, stagflation, and the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act and other union-busting legislation made it more difficult for female workers with their own unique struggles to gain access to union protections.

In this hostile environment, the story of a unified front of female workers unfolds in Folly. Though the novel is named for the main character, multiple narrative voices weave together to create an impression of a movement and time—Martha, Folly’s neighbor; Mary Lou, Folly’s teenage daughter who supports her family during the strike by bagging groceries at the local market; Mabel, a Black factory worker and labor organizer; and Lenore, Mary Lou’s friend and coworker who helps with the strike by transporting women to and from the pickett line. Collectively, these characters give voice to the struggle the women are facing, their hopes and dreams, and their ability to liberate themselves from the economic precarity that isolates them from one another, even as they work side by side.

Brady’s choice to use different points of view within her slim novel also allows her to realistically portray the challenges of organizing, and the deeply embedded racism the Black women in the southern factory face. Upon entering an organizing meeting, Mabel reflects that “she wished this meeting was a resting place for her, as it seemed to be for the white women.” The Black women are much more vulnerable to retaliation than the others, and regardless of what happens with the strike, they face the realities of a decade of violent, white supremacist escalation. Even when Mabel’s leadership and organizing skills are acknowledged by Martha and Folly, she is not afforded the chance to be a representative for contract negotiations because they know she will not be welcomed at the table. Despite this, Mabel is able to recruit enough Black women to win the vote for unionization, and Folly, recognizing her own internal racism, is eager to inspire others to change:

There were women, even among the organizers, whom she didn’t think really saw the Black women for how they were. Often, she felt like giving up tolerance for them, grabbing them by the shoulders and shaking them, shaking them down to their roots; then other times, she knew they were her, one hair over, and knew they could learn.

Brady’s choice of multiple narrative points of view is one of the many ways in which Folly pays homage to the Realism penned by writers of social change during the United States’s earliest labor struggles: Brady’s sentences hold the rhythm of her speakers; she employs a polished vernacular; the book is earnest, compelling, and accessible, but most of all optimistic—a palate cleanser for the contemporary reader tired of overly-contrived, overly-clever Great American Novels with Nothing to Say. The strike allows the women in the town to experience a deep, lasting love for one another, most notably between Martha and Folly, whose romantic relationship is portrayed with moving candor. But bonds are also made between Lenore and a Black woman who works at the town diner, between Mary Lou and lesbian Lenore that help her understand her mother’s own coming out, and between Mabel and Folly as they work together to organize the Black and white women in the struggle against oppression.

Like many earlier Realist novels, Folly’s message is expressly political—pro-labor, feminist, anti-racist, queer positive. But Brady also doesn’t shy away from the inherent conflicts of leftist organizing within the heterogeneity of an entire class. The use of multiple narrative points of view at once highlights these conflicts and how they arise from individuals, and yet harnesses them together with the force of movement to show that collective action can produce change. Unlike Norma Rae, which champions an individual within a movement, Folly argues aesthetically and narratively, that together, the many have power over the few.