The Labor of Being Black

Among the indelible moments at the trial of Derek Chauvin, the ex-police officer who lynched George Floyd, was the testimony of witness Donald Williams II, one of the people called to describe the trauma of watching someone be hurt without being able to help them. When a defense attorney asked if Williams, a Black man, got “angrier and angrier,” Williams turned the language on the lawyer with the reply, “I grew professional and professional.” The word “professional” is a beautifully unexpected word choice––one that negates the defense’s narrative while pointing to the very quality the police did not embody that day, or many others. And it points to Williams’s own labor, the job of hiding one’s feelings in the face of grossly unethical realities. Professions, after all, are what we undertake in order to survive.

Such racial performance and linguistic inventiveness are also on display in Douglas Kearney’s Sho, out last week, and Yusef Komunyakaa’s Everyday Mojo Songs of the Earth: New and Selected Poems, 2001-2021, out this summer and available for preorder now. A generation apart, both poets examine the labor of being Black both in and out of the United States. Kearney, who lives in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, wrote the acknowledgments to Sho the week of Floyd’s death.

Sho twists and turns across poetic forms, all written in a language Kearney cobbles together from dialects traditionally considered both high and low. These include a sonnet studded with idiom (“now too far naw too low might catch the blues”) and a sestina-like form called the torchon (“Jig / ger gogglers then bow // housefully”). Even free verse feels solid and shaped because of Kearney’s sonic repetitions across the line (“Seems some want some body bodied into street sweet meat”). Such repetitions are the building blocks of a language that lives outside the rules of institutional English, allowing us a glimpse into a freer future. In the opening poem, “Buck,” Kearney presents a monologue that, like Williams’s testimony, repurposes language in the face of violent authority:

Come and go get it!

We may not fight but you’d like us to, too. Tool cocked back to make a no-way way

you kick yourself in us. Umber-husked, our dirty look a dirty talk, begging for the

something strong in your dom palm what smokes after doing it.You order us scream the shut up.

In just one line––from “Umber-husked” to “dirty talk”––the register slides up and down. Such linguistic performativity represents the way the Black and other marginalized people must reshape themselves regularly for others. Phrases are combined into Frankenstein-like objects (come and go and go get it and come and get it collapse into “Come and go get it!”), and words are repeated in the echolalia of a child learning to talk (“to, too. Tool”). In this voice that recombines and repeats seemingly nonsensical sounds, we are invited to imagine a speaker who is an unhinged citizen of a logical nation, or a logical citizen of an unhinged nation.

Even the status of the speaker as a citizen, however, is questioned. The poem “The Post-” asks: “The pronoun for ‘citizens’: us or them?” This is a valid question in a country where citizenship supposedly accords privileges, yet privileges are withheld from many citizens through voter ID rules, and, for example, Georgia’s recent outlawing of water at polling lines. Citizenship’s foundation is exclusion. Applicants for U.S. nationality must demonstrate “good moral character,” an oddly vague term for a country that tallies taxes to the penny. Kearney sums up the United States and its foundational morality of white supremacy in “First, She cuts the Stems”: “Systems are the end of a rope / and the rope.” A few lines down, a woman cuts peaches from a tree in a visual echo to the Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit,” which is based on a poem written by a Jewish teacher in protest of lynchings.

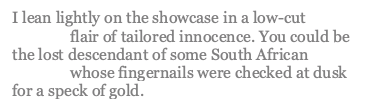

Faced with such bleakness, people take refuge in the body––both those of others and their own (Williams, in his testimony, says, “I stayed in my body”). The poem “Manesology” details how a speaker is asked to comment on “The Problem” in the aftermath of Charlottesville’s deadly white supremacist Unite the Right rally in 2017. The words “The Problem” are repeated five times, succinctly evoking the way white people often fear naming racism (particularly their own) and how they view the populations they have terrorized or marginalized––as problems. In the second half, “The Problem” morphs into “that problem,” then “someone’s problem,” and finally “their problem.” This de-escalation and distancing is done as the speaker takes joy in a partner’s body:

![poem reads: though what we then chose to was kiss awhile. […] after working that problem down to a faint rattle of chains, a vague keen in the walls, we fucked like a burning church.](https://pshares.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Screen-Shot-2021-04-13-at-12.53.10-PM.png)

Even in sex, the speaker and his partner cannot fully escape. The simile of a church conflagration references the destruction of Black churches that began after Brown v. Board and that continues today—most recently when the son of a Louisiana sheriff’s deputy set fire to three hundred-year-old churches in a ten-day span in 2019.

The intertwining of sex and violence is also part of Komunyakaa’s Everyday Mojo Songs of the Earth, a collection of poems from the past two decades. The book’s heart is the sonnet sequence “Love in the Time of War,” first published in its entirety in Warhorses (2008), which employs personas of men fighting in war and the women who sleep with them. The volta of each sonnet is when sex gives way to war, or the reverse:

Bull’s-eye. Maggie’s drawers. Little Boy. Fat Man. Circle

in the eye. Bayonet. Skull & Bone. Them. Body count. Thou& I. Us. Honey. Darling. Sweetheart, was I talking war in my sleep

again? Come closer. Yes, place your head against my chest.

Like Kearney, Komunyakaa uses pronouns to economically tell a story. The foreigners slated for death shift from the third-person “Them” to the second-person “Thou” to settle––after a stanza break––in the first-person “Us,” a word that enfolds speaker and sexual partner. The collapsing of enemy and lover is part of Komunyakaa’s territory as a reporter veteran of the Vietnam War, when American soldiers decimated Vietnamese villages by day and patronized Vietnamese brothels by night. Komunkayaa slips from the voice of soldier to that of the sex worker later in the sequence:

The slightest lull beckons GIs

to our doors. Oh, yes, the horses

I’ve broken in each lonesome body.I’m the wave ridden beyond chance.

He falls asleep. I whisper in his ear,

& he tells me every signal & secret code.

With its horses and “lonesome” men, some lines could have been plucked from an American country song. Yet even there, small words play double duty, with the “Oh, yes” sounding like a lyric as well as the script the sex worker will recite to a GI. In the final line, she becomes a spy stealing secrets from sleep, underlining her desire to become powerful in a powerless role. It also points to the way Americans imagined Vietnamese during the war, simultaneously pliable partners and deadly enemies. Such extremes are a temptation to lust or violence—the word used to describe six spa workers of Asian descent murdered in Atlanta a half century after Komunyakaa returned from reporting in Vietnam.

Komunyakaa turns his persona skills to white women in “Dear Mister Decoy,” included in 2011’s The Chameleon Couch. A blonde, red-lipsticked shoplifter fingers silver and diamonds while walking in the wake of a Black man, certain that security will be too focused on him to notice her crimes:

Both characters are type-cast: she as the innocent lady of leisure, he as the man suspected of theft because he is professional. In the massive shop of America, even a man wandering the display is working, without his knowledge, for someone else.