The Landscape of Memory

As a writer of nonfiction, memory is the stuff I trade in, and people are often surprised I don’t journal, although I’ve periodically attempted to over the years. Instead, I rely on my “scary good memory,” as my friends call it. Tell me once, and I’ll remember your birthday and the name of all your pets. I’ll also remember your food quirks and the outfit you were wearing the last time we were together four months ago. I’ve learned to trust my memory on multiple-choice and trivia questions because whatever answer pops into my head first is almost always right.

I love this memory of mine, but sometimes I feel awkward or even a little ashamed about remembering so many details of people’s lives that I was only exposed to once. While I may at times relish remembering so much, it can feel suffocating, a wheel of slides spinning too fast, bombarding me with a density of color and light.

It’s my inclination to seek a metaphor for memory: a slide carousel, a library card catalogue, a recipe box. “Maybe some people’s minds are like libraries,” Amy Leach writes in her essay “The Safari” from Things That Are, “with memories like books, and even if the exits were left open the memories would still be sitting on their shelves in alphabetical submission.” She goes on: “Maybe some people’s memories are like furniture, useful…. You happen to have one of those minds inhabited by memories like wild animals, with wandering ways of their own: diffident giraffes, changeable mice, milling birds, clamoring turtles.” The natural world, for Leach, is a whimsical metaphor for memory and our relationship to it.

Expanding on this metaphor, Leach demonstrates that, initially, memories are captured in a zoo before they are irreversibly released: “Once the past is over,” she writes, “you begin to administrate it, locking the days in cages and assembling them by genus and writing explanatory plaques for each.” Memories morph into creatures kept “behind deep moats and electric-shock cables and glass barriers,” an “insane jungle-past” turned “nice zoo park.” She describes, “Thus is the pandemonium of the past civilized, accredited, receiving a retrospective order and sidewalks. Thus is it made secure and navigable, and fun to visit: and thus is it easy to exit.” Although her essays utilize the second person to draw the reader into this wild, lively construction of memory, Leach, too, is initially drawn to the relic, to containment and organization, a sort of sanitizing of memory that makes it both accessible and safe, an album to flip through, then put down.

This approach to memory, however, doesn’t last: “Then you wonder if these exhibits, so perfectly controlled, are sincere,” Leach muses. “The memories seem diminished into listless props for their own interpretative panels. Hadn’t some of them, eyes afire, once chased you down and pounced on you, growling in your ears like berserkers? How are they now so quashed and torpid?” The desire to liberate the memory-animals overwhelms, and so, one releases them unlabeled back into the wild. The experiential safety of contained memories is lost, and now, risk is involved when interacting with them. “Hence what seemed a weird but benign memory, from a distance, while you sat behind your binoculars and formulated plausible theories about it, may all of a sudden charge and leave you, the rememberer, in shreds,” Leach notes of a rhinoceros/memory.

Having both examined the corralling of memory and the releasing of it, Leach considers that “perhaps it was smartest, after all, to collar your memories and isolate them, sedating the irascible ones, banishing the grotesque, systematizing the rest…. Maybe it was best to let only the shadows of your impounded memories touch you.” Eventually, though, “it had begun to be so mind-numbing, to see your memories in their state of moldering stupefaction.” Leach posits that controlling memory is a dangerous thing and that, while it may be appealing to do so, the results are grim, bland—worse, maybe, than the impact of the original memories. We must examine them even if it is at our own risk. Leach enacts the imagination inherent in experiencing memory, whether dangerously or joyously.

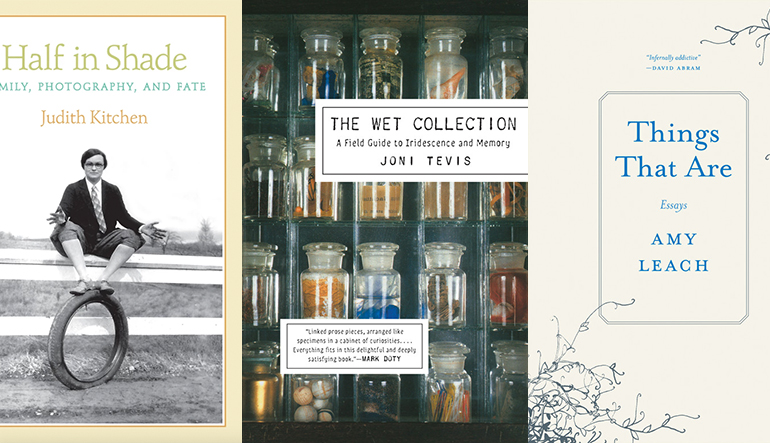

“Imagination fills the aperture, finds the griefs that caused the lines at the corners of eyes,” Judith Kitchen observes in Half in Shade. “And memory reconstructs those griefs, faded now to bearable, but alive and squirming beneath the glossy surface, demanding their day in the brash, unflinching glare of the sun—the hidden ultraviolet damage of it—until grief cannot be glossed over, but finds us out again, and again.” As in Leach’s depiction, memory, for Kitchen, is animate, something that can be “alive and squirming” and “demanding”—something we cannot control.

Kitchen’s memoir is an examination of her family heritage using family photographs and artifacts, and essential to this memoir is the imagining Kitchen does to (re)create memory/the past. Kitchen’s “challenge as a writer was not to describe, but to interact. Not to confirm, but to animate and resurrect. The past became [her] subject, and memory [her] lens. But memory was often insufficient.” To animate, Kitchen must “rely on probability, supposition, intuition, the half known, the partially knowable,” sometimes even fantasy. Memory and imagination, control and creation, must work together to fabricate worlds that are no longer. Kitchen hungers “for the shaping power of language to resurrect experience,” for written records and photographs and memories to be morphed back into a vibrant, animate whole.

In the hands of Joni Tevis, memory morphs from something physical and alive to something more ethereal and intangible while still relying on the connection between memory and imagination. “The iridescence of memory happens when one image (physical) illuminates another (imagined): not quite a reflection, but a refraction,” Tevis writes in The Wet Collection: A Field Guide to Iridescence and Memory. She is often drawn back to the natural world, the landscape of her past. “Some days I think I’ve forgotten, then memory broadsides me,” she remembers, “I’m back in a strip-mall Chinese restaurant, Reno, knowing we have one last night together, and the bottom drops out. How would I relearn solitude?” Tevis’s memory becomes Leach’s rhino, charging suddenly and leaving her in shreds.

In her essay “Warp and Weft,” from The World Is on Fire: Scrap, Treasure, and Songs of Apocalypse, Tevis examines the history of a defunct textile mill down the road from where she grew up in South Carolina. It’s a forbidden place to visit, yet she feels compelled to trespass on its grounds. Tevis, who grew up in the “Textile Capital of the World,” describes a handloom she wove potholders on as a child; despite its presence in the community, however, she missed the mill’s closing when she was in high school. Returning by happenstance as an adult, she wonders what effect being stripped of its identity has on a place: “What does it mean to lose who you are?” she asks. “When people say they miss the mills,” she goes on, “part of what they mean is they miss community. Easter-egg hunts, fishing contests, nicknames.” Like Kitchen, Tevis must dig to reimagine, and like Kitchen’s family, some want to forget the past they left behind or that was stripped from them. “I scoured archives, read oral histories, left messages for folks who didn’t call back. It seemed like people wanted to forget what had been.”

In their essay “They Didn’t Come Here Cowboys,” collected in Waveform: Twenty-First-Century Essays by Women, Alex Marzano-Lesnevich focuses on a “widowed image,” Charles Baxter’s expression for those “memory-images one has that seem to lose their authorship and their tie to the moment they were a part of.” For Marzano-Lesnevich, it is the sickening “clank” they hear when a woman barrel racer collides with the arena’s aluminum support pole at the Angola Prison Rodeo in Louisiana. “In the writer’s mind, the image becomes something else,” Marzano-Lesnevich states. “It swims free and lodges in the murky, grassy seafloor of the subconscious, takes on the detritus of unnameable meaning.” Like Tevis, Kitchen, and Leach, Marzano-Lesnevich reaches for metaphor, personifying memory, and like these writers, Marzano-Lesnevich observes that memory cannot be memory alone—that, instead, memory, and the widowed image in particular, is “something beyond simply articulable fact, yet something that cannot be fulfilled with only imagination. It is where the two meet, fact and imagination, and how memory joins a triad, the glue of this fractured narrative. The spillover, the sticky irresolvability, the falling short of comprehension.”

Our memories are our treasures, but they’re what plague us too. One feels the desire to control memory or else to solidify it. Our widowed images may charge us. We pull together memory with facts and imagination. Virginia Woolf observes that her memory supplies what she’s forgotten. Patricia Hampl notes “the inevitable tango of memory and imagination.” Vladimir Nabokov uses an invocation of the muse in the title of his memoir, Speak, Memory, to call memory forth to convey his past. Memories may surprise and delight, or they may haunt and devastate. Memories may surface unbidden, unremembered for years. In memory, the past, imagination, facts, artifacts, and those moments that blindside us all swirl together.

For most of us, memory supplies meaning and connection to our past selves, our place of origin, a greater world. Memory gives us meaning. “What would we be without memory?” asks W. G. Sebald in The Rings of Saturn. “Our existence would be a mere neverending chain of meaningless moments, and there would not be the faintest trace of a past.”