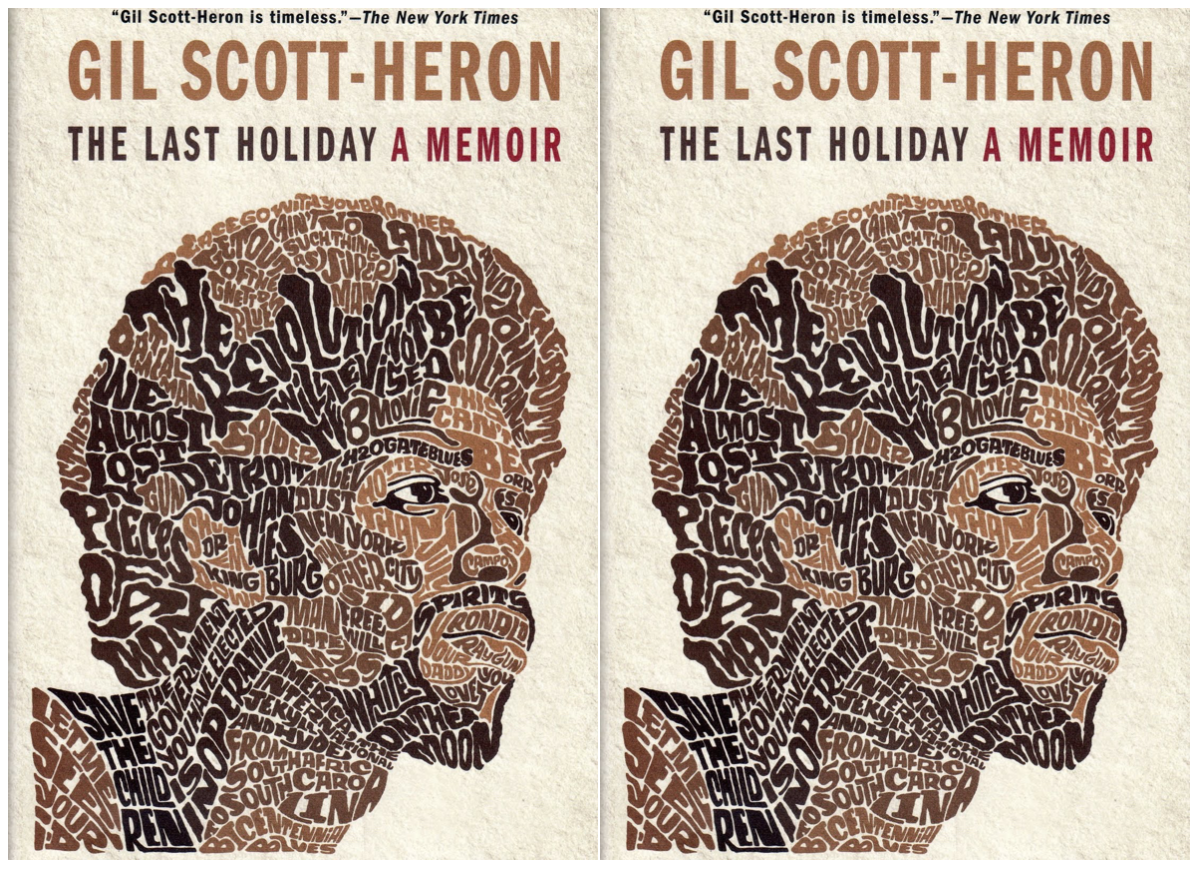

The Last Holiday

The Last Holiday

Gil Scott-Heron

Grove Press, January 2012

384 pages

$25.00

“The first change that takes place is in your mind. You have to change your mind before you change the way you’re livin’ and the way you move.” —1991

We remember him as the bluesologist, the godfather of rap. But for a long time, Gil Scott-Heron thought of himself as a writer: he had two published novels and an MFA from Johns Hopkins before he recorded his first album of spoken-word poetry.

His recent memoir, The Last Holiday was a 20-year work in progress when Gil Scott-Heron died last May, at the age of 62. It was originally written in the third person, but his editors thought this was problematic, and had him reframe into the first person. As a result, The Last Holiday became much more about Scott-Heron’s early life than his original focus: the story of Stevie Wonder’s Hotter Than July tour and campaign to make a national holiday for Martin Luther King Jr.

Still, Last Holiday is a memoir in which Scott-Heron is the observer, not the star. The tone is as if he is reminiscing with friends: always honest, never self-important. His descriptions of other celebrities are casual, yet poignant; Gil Scott-Heron can make us see the wonder in all kinds of people, from his roadie Keg Leg to his grandmother in Tennessee to Michael Jackson himself. Not the blinding light of being a star—the simple glow that lights us up from within. (The spirits, if you will.) In both prose and poetry he lovingly conveys Stevie Wonder’s amazing personal presence, and his tireless commitment to the MLK holiday, and the night of December 8, 1981, when Stevie told him John Lennon had been shot.

The politics of right and wrong make everything complicated

To a generation who’s never had a leader assassinated

But suddenly it feels like ’68 and as far back as it seems

One man says “Imagine,” the other says “I have a dream.”

Interspersed throughout are short poems like this that describe various events: the coming of the Highway through Gil Scott-Heron’s neighborhood in Jackson, his arrival at Lincoln College, and the campaign for Dr. King. In fact, the poetry is in such an iconic voice that at times it makes the prose seem redundant. Imagine if he could have written the entire memoir in verse…

Still, this is a powerful memoir, and perhaps surprisingly, given Scott-Heron’s troubled life, an optimistic one; it focuses not on drugs and demons, nor his failed relationships and failing health, nor on the monumental struggle for social justice. These things are all there, to be sure, but the danger is lurking under the surface, not yet ready to come out. Mostly, the bluesologist calls us to see the spirits in what we have: word and rhythm, family and community. And, as of 1986, a holiday for Reverend King.