The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: Edith Wharton’s Design of New York City from the Inside Out

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a continuation of a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

Regionalism in literature, as we’ve seen throughout this series, generally refers to a book’s external environment; that is, the author’s focus is centered on the accuracy of their chosen place’s sights, sounds, smells, and people. But in Edith Wharton’s fiction, it is the interior of New York City homes that provide context for old New York—her repeated region—at large.

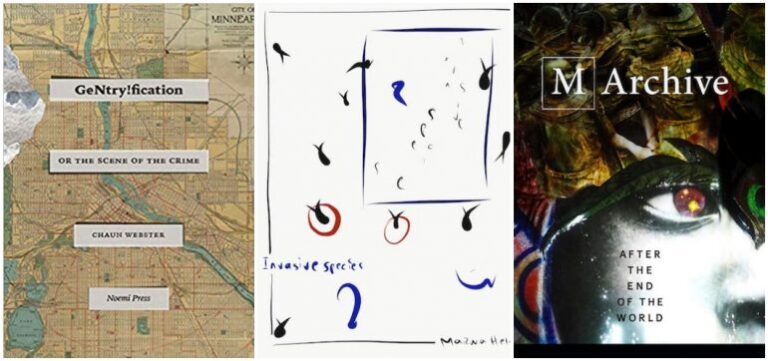

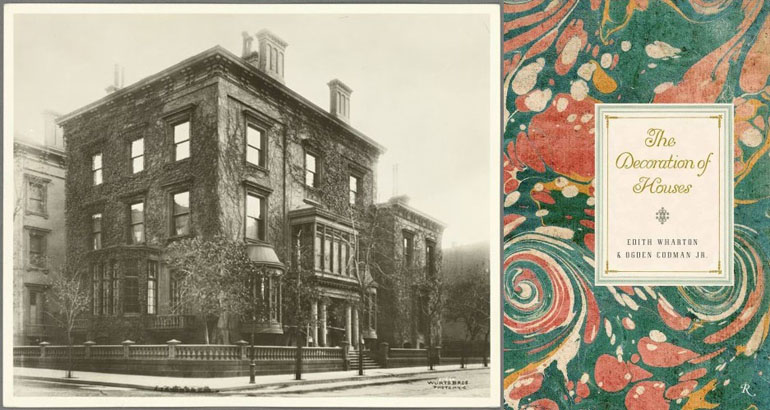

Before The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence, there was The Decoration of Houses, an 1897 manual of interior design co-written with architect Ogden Codman. Though a work of nonfiction, this guide to “appropriateness” in the living spaces of New York high society inspired much of Wharton’s eventual fiction—both her settings and the people that inhabited them. A member of New York’s upper class herself, Wharton’s structural understanding of the city of her birth was both immediate and yet learned. While she inherited status and the carefully curated settings it exposed her to, the role of women in early twentieth century New York was an inheritance she consistently rejected, and thus, her thematic obsession with class, domesticity, womanhood, and aesthetics was born.

Divided into chapters focusing on various elements of the home, The Decoration of Houses illustrates that Wharton’s design of New York in her literature worked from the inside out, proving that a woman could appreciate both the interior beauty of a space, while living life freely beyond the walls of domesticity and with disregard to (glass) ceilings.

In her section on walls in The Decoration of Houses, Edith Wharton emphasizes their role as a source of entrapment undeserving of much attention. In the New York home, walls are practical first, and decorative second. Wharton claims that “the effect produced by a room depends chiefly upon the distribution of its openings” in order to ensure “the comfort of its inmates.” By focusing on the way openings in a wall are distributed, Wharton acknowledges the inherent claustrophobia their presence can create. The relief from the solid, fixedness of the wall (read: doors) is what ultimately allows the room to breathe. Further, Wharton conjures up images of the wall as a means of entrapment by referring to those dwelling within the home as “inmates.” Most commonly associated with prison, this descriptor of women and children, who in Wharton’s era spent the most time within these walls, become captive in the domestic sphere which necessitates openings in the walls even further.

In “Entrance and Vestibule,” Wharton lays the blueprint for how class structures operate in New York City. By exploring the entrances to homes, Wharton sets up the clear distinction between exterior and interior life, or public and private “appropriateness,” as it were. She also touches on who and what is and is not allowed inside of these homes (and the level of wealth that affords them). In her subsequent fiction, Wharton is very critical of these limits and distinctions, but in Decoration of Houses she seems to promote them. However, as someone who values things that are “well-suited,” Wharton is strict and amoral with regard to the pretension of exclusion in a nonfiction design manual, whereas in her literature she is able to abandon the restrictions of her society, both in terms of her wealth and her womanhood.

“It should be borne in mind of entrances in general that, while the main purpose of a door is to admit, its secondary purpose is to exclude. The outer door, which separates the hall or vestibule from the street, should clearly proclaim itself an effectual barrier.” The primary and secondary purpose of entrances parallel with the ways Wharton critiques privilege. She uses the example of a front door to make a tangible example of the way New York high society accepted some and denied others. And “the outer door” Wharton speaks of here is reimagined in her fiction as superficial demonstrations of politeness and wealth, creating a barrier between what the world sees and what truly exists on the inside.

Wharton’s treatise on interior design directly reflects the architecture of her mind. As a woman who preferred books to men and traveling to domestic limits, she understood the importance of rejecting the one-sidedness of traditional gender roles, opting instead for well-roundedness, much like in the structure of her preferred homes. She mused: “If proportion is the good breeding of architecture, symmetry, or the answering of one part to another, may be defined as the sanity of decoration.” The symmetry Wharton promotes in design becomes the same symmetry of personality we see in her characters, namely Lily Bart of The House of Mirth. Beautiful but alone, born wealthy to dying impoverished, Wharton creates a “sanity” in Lily’s interior through her use of symmetry, or what I’d like to call a Whartonian balance of experience—something all of her books are designed around.