The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: The Poetics of William Carlos Williams’s “Paterson”

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a continuation of a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

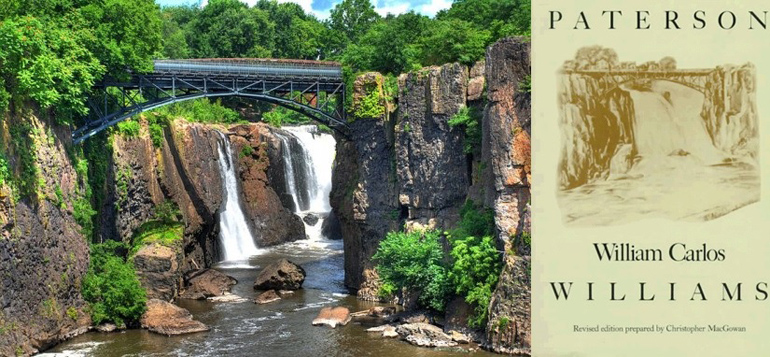

If New Jersey is oftentimes known for being perpetually overshadowed by its neighbor New York, then William Carlos Williams’s epic five volume poem entitled “Paterson” certainly helped put it on the map. First published in parts between 1946 and 1958, Williams personifies the city not only through referring to it as “him,” but also by giving it a continued consciousness; he divides “Paterson” into distinct volumes that are complete yet bleed into each other, much like seasons in a life. The Puerto Rican American poet treats his native New Jersey with equal parts detail and abandon, making his choice to use the poetic form all the more appropriate.

Williams, a member of the modernist movement, was known for such complementary contradictions. In fact, perhaps it was the rapid growth of cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that inspired such devoted focus on one city in particular. Though Paterson is smaller, and more precise, than the Tri-State region it exists within, Williams’s interview with the city ultimately reveals much about America at large. But beyond the physical terrain it illuminates, Williams’s odyssey of a single place also sheds light on the thoughts that live within it. Experimental in form, “Paterson” gives language to a place, a place understood to be an amalgamation of its people. Ever loyal to his quest for poetry to reflect the true speech of American citizens, Williams’s epic off roads intentionally: swerving between classicism and colloquialisms for the sake of a specific sound.

Starting from the book’s preface, Williams makes it clear that he intends for Paterson to be the lens through which we understand the world: “To make a start, / out of particulars / and make them general, rolling / up the sum, by defective means . . . ” True to his interest in the authenticity of place and personhood, Williams acknowledges the imperfections of Paterson’s details without any apology, allowing the city’s “defective means” to be part of his quest for the “rigor of beauty” he’s searching for just a few lines prior. And when the poem officially begins on page one, his quest underway in earnest, Williams places us within that beauty; a move most convincing in the world of an epic poem, its boundaries loosened by time and location. “Paterson lies in the valley under the Passaic Falls / its spent waters forming the outline of his back. He / lies on his right side, head near the thunder / of the waters filling his dreams! Eternally asleep, / his dreams walk about the city where he persists / incognito. Butterflies settle on his stone ear.” From the poem’s first line, Williams gives his chosen setting depth. The immediate contrast between the height of the Falls and the valley where Paterson rests creates a visual dynamism not unlike the spikes and falls of a heart monitor—making the city human upon introduction. Its heartbeat now felt, Paterson becomes a man, his body and dreams made real by environment.

But what is it to exist in an environment but not be seen? Paterson’s dreams are mobile, traveling even; but it is the body, Williams argues, that is sometimes held hostage by setting and circumstance.

Throughout the epic, these types of questions repeat themselves in different voices, asking this city—this person—what they see. “If ever I see you again / as I have sought you / daily without success / I’ll speak to you, alas / too late! ask, / What are you doing on the / streets of Paterson? a / thousand questions: / Are you married? Have you any / children? And, most important, your NAME!” By book five of the poem, Williams’s journey continues, its interests insatiable, hoping to meet another Paterson. The knowledge that this city is at once precious in its particulars but metropolitan in its scope is what keeps the poem—and Paterson—rigorous in its beauty.