The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: Truman Capote’s Shifting Proximity to New Orleans

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a continuation of a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

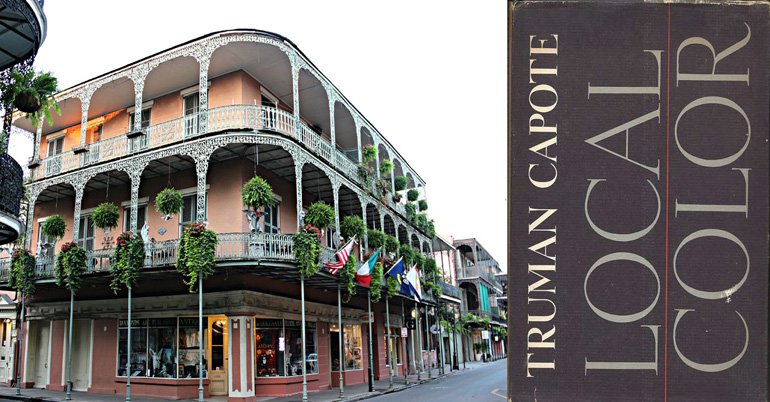

In 1924, Lillie Mae Faulk went into labor while living in the Hotel Monteleone in New Orleans’s French Quarter. Though her son, Truman Capote, would later be sent to live with relatives in Alabama and spend his teenage years in New York, the writer often returned to New Orleans, his hometown. In his 1950 book of essays entitled Local Color, Capote writes detailed observations of the cities he visits, the first among them his Louisiana home.

Describing it as a “secret place,” Capote writes on New Orleans as if it is impossible to know, despite having grown up there. His observations feel, at times, like those of a tourist who is visiting New Orleans not the first, but perhaps the third time; Capote’s familiarity with the city is only usurped by his wonder:

New Orleans streets have long, lonesome perspectives; in empty hours their atmosphere is like Chirico, and things innocent, ordinarily (a face behind the slanted light of shutters, nuns moving in the distance, a fat dark arm lolling lopsidedly out some window, a lonely black boy squatting in an alley, blowing soap bubbles and watching sadly as they rise to burst), acquire qualities of violence.

Here, Capote first illustrates the tension he feels surrounding his ever-changing proximity to New Orleans. He declares his familiarity with the city only to admit to some uncertainty regarding what it is he sees. Capote’s perspective on New Orleans is warped by his departures—images once true to him become less so as the innocent turn sinister, and the streets become as two-dimensional as paintings, fixed and forever. Capote’s observations of the city change in scale and shape, thanks to both his frequent uprooting and, perhaps, the city’s historically Southern Gothic mystery.

Capote seems to be equal parts enamored and bored with the “essential simplicity” of his hometown. “N.O., like every Southern town, is a city of soft-drink signs; the streets of forlorn neighborhoods are paved with Coca-Cola caps, and after rain, they glint in the dust like lost dimes.” Having lived in more than one town in the South, Capote has created a template for understanding his environment, no matter which Southern town he’s in. However, the magic of soda caps shining like new silver on streets that buckle with age is an observation that many might see, but few notice. It is his spellbound attention to New Orleans that places the young Truman squarely inside the world of Louisiana, no matter how much he tries to reduce it to a Southern town among many others.

The ways in which Capote illustrates the people of New Orleans makes his later invention of the “non-fiction novel” genre unsurprising. In this early work, we already see him toggling between truth and fiction, closeness to and distance from his subject. His intimacy with people like Miss Y., a somewhat anonymous female figure who has known Capote since he was a child, is made clear by his analysis of her personality: “She is like the piano in her parlor—elegant, but a little out of tune.” He is aware of the musicality of her movements, and finds her utility classic, but she is just distant enough from him for their relationship to be off key. This separation is made more obvious by his assessment that “Miss Y. does not believe in the world beyond N.O.; at times her insularity results, as it did today, in rather chilling remarks.” Because of his time spent in Monroeville, Alabama (where he would befriend another literary giant, Harper Lee) and in New York, Capote’s sense of various local colors was vibrant. Unlike Miss Y. who never left the jewel-toned streets of the French Quarter, Capote is able to frame New Orleans with a different level of exposure, but one that removes him from the folds of home and those who knew him.

Simultaneously a local and a returning tourist, Capote moves through New Orleans with the help of environmental landmarks, noting the “signs everywhere, chalked, printed, painted” with bashful gratitude, their presence a visual cue for everything he might have forgotten. When reflecting on his childhood in the Big Easy, Capote remembers a man, Mr. Buddy, who lived in his building. “His balcony, smaller than mine, was screened with sweet-smelling wisteria; as there was no furniture to speak of, we would sit on the floor in the green shade, drinking a brand of gin close kin to rubbing alcohol, and he would finger his guitar, its steady plaintive whine emphasizing the deep roll of his voice.” Perhaps the fiction in Capote’s nonfiction comes from his reliance on the senses rather than the reporting of words. The writer does not give Mr. Buddy much of a voice, but he does give the older man’s environs a scent, a situation, a sound. For Capote, the wisteria in bloom says just as much about New Orleans as their conversation does. And when Mr. Buddy is given sound beyond his guitar, Capote notes, “He could carry on this way until moonrise, his voice growing froggy, his words locking together to make a chant.” This chant, memorable in its repetition, is one that seemingly never lets Capote stray too far.

But Capote, in true journalistic fashion, yearns for the new truths that come from exploration. As his curiosity grows, the chant of New Orleans weakens. “There are new people in the apartment below, the third tenants in the last year; a transient place, this Quarter, hello and good-bye.”