The Market Wonders’ Exploration of Poetry and Financial Markets

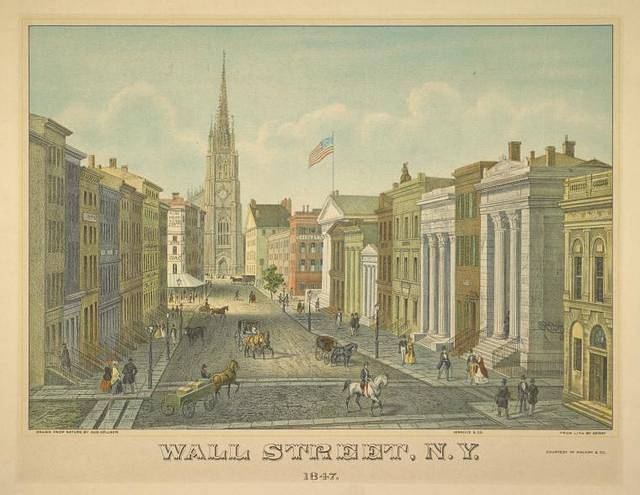

“The poem and the stock market welcome speculation,” writes Susan Briante in her 2016 book of poetry, The Market Wonders. “The poem is a high-risk investment, a long-term commitment. Like a big dirty city, it should make you feel / a little uncomfortable.” Poems, like financial markets, are often trusted to an anointed, authoritative few for interpretation. They cause discomfort because they can often be sites of volatile change, their movements cryptic or foreign. Those who speculate about the stock market might like to believe that it is governed by natural, self-regulating laws of supply and demand; that if we just grant the market enough autonomy, it will take care of itself; that unlimited growth potential is both desirable and possible. The machinations of its algorithms and financial instruments are complex and esoteric, but some believe that the market holds special insights for those who decipher it properly. The Market Wonders meditates on the supposed prophetic powers of the stock market, performing a divination of numbers much like the I Ching, and punning Tao with Dow (Jones Industrial Average). The speaker of the poem attempts to draw connections between the mercurial rise and fall of the Dow, the banal routines of our everyday lives, and the ways we have all learned to read our self-worth in the value calculations of an inescapable and oppressive market. In doing so, Briante calls attention to an obvious yet perhaps overlooked aspect of the world of finance capital: it is not materially real. Our financial system is no longer dominated by an exchange of material goods but is instead dominated by an exchange of abstract financial products. This high degree of abstraction obscures the ways we are forced to submit to the market’s algorithms, since market values have naturalized themselves as the only form of accounting that matters.

Much of The Market Wonders records time in terms of the position of the Dow Jones Industrial Average at the end of a day’s trading. Phrases such as “October 14—The Dow Closes Up 10015” and “December 16—The Dow Closes Down 10441” appear in the top right corner of the page like diary entries. In many parts of the book, a portion of the poem is located above a separate running commentary in a footnote below, giving the footnote the appearance of a scrolling stock ticker. There is an obsession with numbers, counting, and calculations throughout The Market Wonders. The footnote section of the book depicts “a prophecy a litany of calculations” in the Bible’s Book of Revelation: “40 and 2 months 2 witnesses 200 and 3-score days / 2 olive trees 2 candlesticks in a singe of data John like a physicist scavenges for God.” Accounting, the act of taking numerical tally of all things, foregrounds the world’s destruction. For Briante, numbers provide a connection between the physical world and the spiritual one. Numbers record quantities of concrete objects in the physical world but also embody sacred representations in different cultural and religious texts. Briante writes, “9 + 5 + 0 + 9 = 23 2 + 3 = 5 / 5 = freedom, adaptability, unpredictable travel, abuse / of the senses…1 + 0 + 4 + 4 + 1 = 10 / 1 + 0 = 1 / 1 = Creativity, independence, originality, ego, the unity of all things, symbolized by a circle.” These tabulations parody the numerology of the I Ching, an ancient Chinese text of cosmology and philosophical commentaries. Numbers in this sense are abstracted into ideas and used symbolically for decision-making purposes. By contrast, the numbers of financial markets are often read with a kind of matter-of-fact reportage, since we assume them to be completely divorced from any kind of mystical-spiritual ambiguity. They derive their authority by claiming to point to something real, exact, and measurable in the world. Briante invites parallels between these different functions by emphasizing the calculations of both worldly and metaphysical values throughout The Market Wonders. Yet Briante also satirizes the idea that a numerology of the stock market may offer a synthesis between this world and the next. She writes, “The theoretical physicist says, ‘I’ve always wanted to find the rules that governed everything.’ / The theoretical physicist says, ‘Deep laws emerge.’” What are the deep laws of the market?

Briante pokes fun at a logic that assumes the “deep laws” that govern financial markets correlate in meaningful ways to the minutia and specificity of everyday life: “The Dow rises above 10,000. / My dog scratches his ear. A lamp buzzes on its timer. Rains / clear and the cold / arrives. The unborn / keep their distance. / I make a dinner of brown rice, butternut squash and kale: / some [thing/event] or my 3000 / nerves bristling in the air.” This is not to say, however, that The Market Wonders argues that the market bears no consequence whatsoever on our day-to-day existence. In a section of the book titled “Meditation,” a law of averages has direct and perverse implications for the most trivial aspects of our lives: “Imagine a chart of median family incomes / as big as the parking lot— / use it to determine where to abandon your car.” On their surface these lines read like an absurd joke, but there are some implications that one can draw from a chart of median family incomes—most people have an intuitive sense of the neighborhoods in which they feel safe leaving their car parked overnight, for example. Briante later writes,

When we lived in the two-bedroom house on a busy street on the fringes of a ‘good’ neighborhood in Dallas, once every couple of months I would hear gunshots, often on Saturday nights usually late enough that I was in bed.

We purchased the house through the Obama tax credit program for first-time homebuyers, a response to the economic crisis of 2008 and the housing market crash. Because we could not afford to put 20 percent down, we had two mortgages, the second of which included a balloon payment.

We purchased the two-bedroom house on a busy street on the fringes of a ‘good’ neighborhood in Dallas because we were trying to have a baby and the neighborhood had the best public elementary school as well as two Montessori charter schools.

In a very real sense, the exchange of abstract financial products, the deep, immaterial laws that make up the arbitrary structures of our current financial system—a tax credit program, a down payment percentage, a mortgage, etc.—can influence a person’s daily circumstances. Housing market values determine the boundaries of “good” and “bad” neighborhoods. They can also determine the life outcomes for children growing up in those different neighborhoods. Briante writes, “The market scans my child, calculates pecuniary value.” It may be the case that we have much less agency than we are comfortable believing when it comes to the determination of our self-worth. Where one lives, what schools one’s children might attend, or what relationship one may have with police—these are all factors pre-determined at least in part by an abstract system of financial valuation.

At the heart of The Market Wonders is an investigation into the repercussions of an unwavering faith in fictitious capital. Fictitious capital is a representation or simulation of wealth that can itself beget more wealth. While historical materialist perspectives after Karl Marx assume a real, material object for their critique, the “material” basis of finance capital, contrary to classical studies of labor and commodities, is and always has been immaterial, abstracted, and ultimately fictitious. In her book Realizing Capital: Financial and Psychic Economies in Victorian Form (2014), the scholar Anna Kornbluh argues that an analysis of the structural dimensions of the financial crises caused by fictitious capital in Victorian England were subsumed by a fascination with its psychological dimensions.

It is difficult to ground finance logically, so many finance journalists of the time shifted the ground for understanding the economy to the psychological dimensions of investors. The financial economy therefore depended for its development on disavowing the inherent fictiveness of all credit and the creation of what Kornbluh calls a “psychic economy” as its object of critique. Financial systems of credit and debt therefore rely on establishing a certain degree of faith that a creditor’s money will be repaid (with interest). Investment in a 401k plan relies on a kind of faith that the money put into it will grow over time and be available for withdrawal at the time of retirement (and not destroyed in a 2008 housing market crash). Purchasing stock in a company is little more than gambling. Financial products become a kind of poetry, a making-things-up with words, writes Kornbluh in her essay “The Matter of Fictitious Capital” (2015). This is why she thus calls historical materialism “materialism without matter.” It is an act of faith that the financial system will continue to function since there are few material underpinnings.

A system built on fictitious capital will always be precarious and need ways to reproduce the trust necessary for its operation. A psychic economy helps to reproduce this trust by shifting explanations of economic crises onto individuals: poor people are poor not because of the precarious nature of a system of fictitious capital, but because of their own moral failing or lack of intelligence in navigating the financial system. As long as people believe their circumstances are temporary and can be overcome through an individual effort of playing the game of the market better, they have little incentive to change this game. To succeed in a market dominated by fictitious capital requires submission to an oppressive regime of (ac)counting and valuation that seeks to obscure and naturalize the violence of transforming a person into a number—their net worth.

Contemporary culture has become saturated by the language of financialization. Financial jargon can sometimes even take the form of a mantra or incantation. Briante writes, “I default, I default, I default.” The line contains an element of Catholic penitence in its tone. Financialization has become the new spiritualism. Hobbies revolve around making money. We all speak in the metaphor of investment now, investing in our future selves. The scholar Max Haiven, in his book Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life (2014), writes that “metaphors function to hide social violence—they often work to disguise or normalize unstated or unacknowledged ideological assumptions.” Briante writes, “Mother is Marxist, exposing as false and pernicious the mystification of capitalist instantiations of value, promiscuous relations of value and their violence.” The Market Wonders illustrates that the metaphor of market value is not only hollow but violent, since we have no choice but to be interpellated by it. The market scans us, calculates pecuniary value; in return we must surrender everything else.