The Moral Universe in Ninety-Nine Stories of God

When I wear my mirrored sunglasses, I notice that my kids love to see their own reflections in them, but they hate not seeing my eyes. My eyes, it seems, are fundamental to their knowledge of me, my moods, my reactions to whatever shenanigans they’ve gotten themselves into. I watch them grapple with indeterminacy, amuse themselves while waiting for my eyes to reappear, and start to panic when they don’t.

I wonder what would happen if I wore my sunglasses all the time, night and day, inside and out. I imagine my kids would adapt, that they’d find other ways to gauge me, to understand me—which is to say, figure out who they are in relation to me, what they can get away with, and what actions they might take to achieve their desired outcome, like affection, a bowl of ice cream, access to the TV, staying up late, a trip to the park.

Fiction writer and essayist Joy Williams wears sunglasses all the time. According to an interview with The Paris Review, her proclivity’s origin story goes something like this: she was about to give a reading when she discovered she only had her prescription sunglasses with her, so she put them on and never stopped wearing them.

A passage in the story titled “NOCHE,” the second in her collection Ninety-Nine Stories of God, reads:

Another something that could be the basis of the dog’s behavior was the fact that her mistress always wore sunglasses, day and night. Like everybody else, the dog never got to see her eyes. When the woman had people over, she placed a big bowl of sunglasses outside the front door and everyone put on a pair before entering. It was easier than locking the dog in the bedroom.

In other words, the dog has become used to inscrutability. It has grown accustomed to noche, to night.

It occurs to me that Joy Williams in her sunglasses might be a walking metaphor. It occurs to me that in Williams’ world, God is also wearing a pair of mirrored sunglasses, and after we tire of making funny faces at ourselves in His lenses, we start to panic. We wonder what He may be thinking, because without God’s eyes, how can we know whether or not He exists? Without His eyes, how do we know if we’ve won His approval, His fury or, even worse, His ambivalence?

Past generations found ways around or perhaps directly into this conundrum, ways of speculating—like telling stories or reading nature’s signs. To paraphrase writer Philipp Blom’s thesis in his historical study Nature’s Mutiny, climate change during the sixteenth and seventeenth century’s Little Ice Age challenged the survival tactics and belief systems people had been clinging to for hundreds of years prior, and so the Enlightenment was born.

Now here we are, facing climate change again in the twenty-first century. Will humans adapt? Can we imagine a world in which we aren’t the center? Can we imagine an economic system that isn’t based on exploitation? In fact, can we reimagine nature? If philosophical debates happen, they are happening in art. They’re happening in story. In story, we can toy with various scenarios, possible outcomes. We can even use nonfiction as conduit for speculation and invention. In art, we can play the role of God and absent ourselves or reveal ourselves as we see fit. “We need to change the metaphor,” Blom says, and what I believe he means is changing our understanding from nature as clockwork—a mechanism turning around the human at its crux—to something different, perhaps something hard for us to conceive, our minds bent as they are in a certain direction.

Joy Williams has a bent mind. Delightfully bent. In her created universe, God is ambivalent if He’s even there at all; what matters most is that humans stumble into cruelty, whether intentional or not, whether enormous or petty, against a backdrop rich in other species. In Williams’ universe, dogs are watching us. Pigs, cows, and horses are watching us. They bear witness as well as the brunt of our exploitation, as does the land, as do the trees, the air, the water. That we can’t acknowledge their pain is indicative of our lack of imagination. But Joy Williams has just such an imagination.

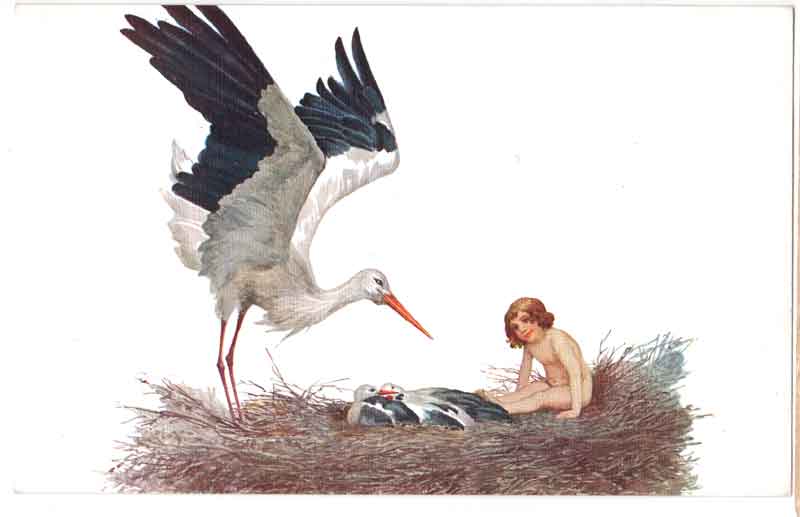

Story number fifteen in Ninety-nine Stories of God is called “STORY.” A grandmother reads a Hans Christen Andersen fairytale to her grandson called “The Storks.” “STORY” strikes me as fundamental to Williams’ project, and that is to estrange the reader, to cause the reader to see the world again, and differently.

Andersen, who wrote fairytales in the nineteenth century, was in effect emulating an old artform, imbuing it with his own contemporary concerns and obsessions, one of which was Christian morality. In his story “The Storks,” human children mock a family of birds and threaten to kill and eat them. In revenge, the storks deliver a dead baby to the bad child and living babies to kind children who chose not to taunt and scare the storks—an act predicated on the idea that storks fetch human babies from a lake where they wait, dreaming, to be born. The dead baby, the story tells us, “dreamed himself to death.”

Williams doesn’t let this tidbit of information go by without mentioning it. After all, it’s an odd aside, suggesting the unborn baby, so in love with the perfection of his dreams, wouldn’t relinquish them to the living world.

How does one explain stillborn babies? How does one threaten children into good behavior? What’s our responsibility to the natural world? The fairytale asks its readers to let go of scientific truths in lieu of metaphorical ones and so, in many ways, the fairytale is the perfect genre for our moment. If the scientific method—shaped during the Enlightenment—fails to convince us, then we look to “STORY,” a story so strange and so cruel, so lacking in remorse, it could only be a fairytale. The grandmother in Williams’ retelling of Andersen’s “Storks,” reads the passage about the dead baby and both she and her grandson are shocked:

The boy and his grandmother looked at one another in horror. As fate would have it, the mother was with child by the father, but several months later the infant arrived stillborn. Of course, it was not the little boy’s fault. He had never sung a cruel and hurtful song about young storks.

His grandmother, his best and most faithful friend and advocate, lost her mind shortly thereafter, whereas he grew up to be a formidable jurist, quite ruthless and exact in his opinions, none of which in his long career was ever overturned.

In this last paragraph, which serves as the story’s epilogue, the narrator tells us that the grandmother “lost her mind” as a result of what can only be described as a dreadful coincidence, while the son grew up to become a judge, an expert in the law, and “ruthless”—a contrast meant to underscore humanity’s disparate responses to chaos. “STORY” itself is a response to chaos, an attempt to shape and give meaning to that which has no meaning. And yet, the fairytale offers no logical answers, existing as it does in pretense. Can’t we, Williams implies, say the same of God?

In story twelve, titled “NO,” a mother has lost a child to infection. As a way to honor her memory, she hangs the girl’s favorite rabbit-fur muff in a tree, thinking the birds will use it to build a nest, though, the narrator tells us, “she went through the albums and boxes of photographs, but she could find no picture of Iris with the muff.” Already the premise for the mother’s offering seems precarious, built on grief, faulty memory, nostalgia. But nature, in Williams’ story world, has no use for these things, and a human’s death is no more significant than a rabbit’s.

This is a cruel story. It’s hard to position ourselves in it. It’s hard to get our bearings, to draw up a hierarchical pyramid that doesn’t have humans at the top, never mind God.

And who is God in Williams’ Ninety-Nine Stories of God? In story six, “SEE THAT YOU REMEMBER,” and story seven, “NOT HIS BEST,” He’s a trickster muse, permeating Leo Tolstoy’s and Franz Kafka’s dreams. In “NOT HIS BEST,” Kafka dreams that he is “not a human being,” and that he throws himself out window onto trains tracks where, he says, “‘trains came, one after another they ran over my body, outstretched on the tracks, deepening and widening the two cuts in my neck and legs.’”

In Williams’ rendering, Kafka, through his God-given dreams, has insight into the non-human experience, about which “he frequently fretted,” the narrator tells us. He is destroyed by industrialization, its human-centric time, its human-made violence. “I didn’t give him that one,” God says at the end of the story, meaning the dream, the image, the metaphor. He can’t or won’t take credit for it.

In “FATHERS AND SONS,” wolves discuss their persecution by humans with God:

Thank you for inviting us to participate in your plan anyway, the wolves said politely.

The Lord did not want to appear addled, but what was the plan His sons were referring to exactly?

Of course, in Williams’ fables and parables, in her fairytales and anecdotes, there is no plan; though empty gestures toward meaning arrive, they lead nowhere except perhaps back to themselves.

The ninety-ninth story of Ninety-Nine Stories, titled “THE DARKLING THRUSH,” imagines God at a psychic’s house. The psychic tries and tries to “see the Lord, but nothing was coming through.” After some reflection, the psychic thinks,

Maybe she didn’t have to see Him. Maybe she was putting the cart before the horse in this case. Maybe she should just go directly to the question most everyone has and visualize from there.

What’s going to happen after I’m dead?

The story is named for a Thomas Hardy poem in which a narrator walking through a winter landscape he compares to “the Century’s corpse,” finds comfort in “an aged thrush” that “had chosen thus to fling his soul / Upon the growing gloom.” The sight and sound are so incongruous to the narrator, he believes the birdsong is “some blessed Hope, whereof he knew / And I was unaware,” and so Williams’ story, by placing the title in place of a coda, leads us back to the poem and to the poem’s existential concerns. Is salvation possible and, if so, does its sole possibility lay in the natural world? But what if we can no longer saturate nature with self-satisfying meaning? Nature resists meaning, and the bird can’t know hope in the sense that humans know it; it can only know itself. The psychic in Williams’ story can’t know God because, like the one-hundredth name for Allah, He is ineffable. She can only see her own reflection in the darkness where one might expect to find His eyes.

This piece was originally published on June 17, 2019.