The Ploughshares Round-Down: Stop Fearing the Business of Writing

Last week, Guernica published an interview with art critic Ben Davis, which begins with Davis questioning the premise that “the central tension of the art empire is that between creativity and money.” Davis says there can obviously be tension between what sells and what an artist wants to express, but he argues that money also funds innovative creative work. “If things were as simple as the equation ‘success = corruption,'” he states, “then you wouldn’t need [art] criticism.”

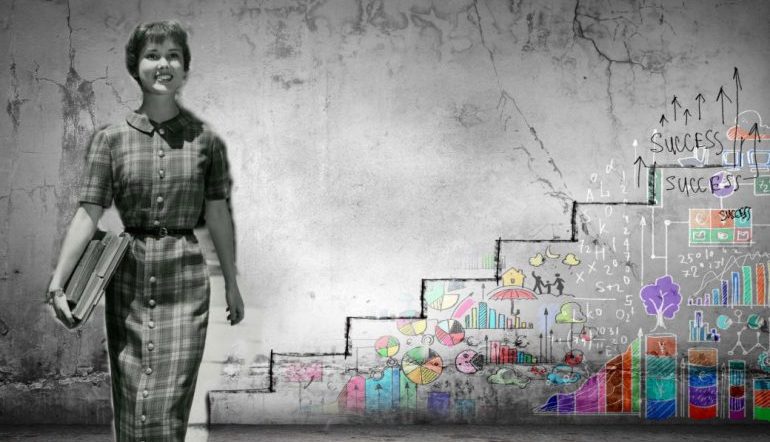

The same misguided equation has long haunted the writing world. It’s with trepidation and/or resignation that writers dip their toes into Literary Business, and it’s often with suspicion that readers observe the marketing tactics of writers we love. Why? Mainly because we’ve been told for ages that financial success implies selling out, and that any desire to make money from literature (or even to amass readers!) is indicative of having devalued Lit for the sake of consumerist advancement. We assume that “business”–a fast-paced, bottom-line-focused enterprise–is fundamentally opposed to the slow-paced, journey-is-the-destination mentality required of deep reading and serious literary engagement.

Fortunately, none of this is necessarily true.

It can be, and let me be the first to say that if you want to get wrapped up in advances, paychecks, and celebrity-seeking, the path’s there for the taking. But if materialistic obsessions don’t appeal to you, that doesn’t mean business can’t appeal to you. Knowing what to do with your work once it’s written (my definition of “business savvy”) doesn’t equal becoming a materialistic, consumer-pandering sellout. Seriously. And it won’t corrupt your art. Here’s how to begin your Business Rethink:

1. Know Your Fear.

On top of our Corruption Fear, creatives (writers, artists, musicians) are often uninformed about–and intimidated by–business. Most of us haven’t studied marketing or obtained an MBA. So our fear of being corrupted can be a clever guise for our real fear: failure. We’re daunted by the biz smarts we don’t yet have, and we feel stupid for not having them. It feels better to tell ourselves we’re opposed to marketing on principle.

Fortunately, a lot of great teachers have begun addressing writerly Biz-Aversion by teaching business in MFA programs and even high school creative writing courses. And there are increasing resources online to teach you how the publishing process works, how to pitch/submit/be rejected, how to “build platforms” (or NOT), and how to market your work– all of which can help allay the fears that keep you paralyzed (and unread). Meanwhile, we can also address the fundamental, creeping fear that business somehow eats part of our artistic souls:

2. Define “Readership” for Yourself.

The task of “accumulating a readership” will always sound cold and gross if “readership” is just a thing you want so you can feel bad*ss. If you think of “readers out there” as blank, nameless faces whose sole significance in your life is that they might find your book and/or tell a friend about it, then yes–reaching out to them will feel soulless. It is.

The solution? Humanize your potential readers. They’re people with their own stories, thoughts, desperations, needs, whims, and failures that can (and perhaps should!) interact in some way with your words. They aren’t just sources of money, Likes, Shares, or Amazon reviews.

This can sometimes frighten writers who are introverted, who fear that “humanizing your readership” means “learn to gregariously love crowds.” Ew, I wouldn’t be on board with that. So here’s the good news: No Gregarious Crowd-Loving Necessary. Your choice is NOT between A.) exuberantly making friends with EVERYONE EVER and B.) turning “readers” into some impersonal monolith to which you’ll eventually chuck a manuscript, in vague hopes that they’ll respond with cash. That binary is rubbish. Just give your readers definition and personhood. Reach out to them as people who stand to be deeply affected by your writing and your self. That’s good business.

3. Consider the Alternative.

I came to the writing world from a career as a performing songwriter. As writers of books, articles, poems, etc, we usually invest in our manuscripts, only to send them off into what feels like the ether. But performers have the (sometimes frightening) advantage of having our listeners right in front of us. So I’ve been able to witness my songs meeting listeners for the first time: seen them as they’re received, observed them hitting home or completely missing. At its best, this creates an intimate cycle of writer/listener feedback. It’s easily one of the greatest gifts of performing.

That experience has permanently shaped how I view business. As a performer, when I look out at rooms full of listeners, I know they wouldn’t be there without the time we spent on press releases, radio interviews, marketing strategies, and social media posts. Without business, those amazing people in front of me–so many of whom talk to us after shows, share their own stories, buy our records, and connect with us (and each other) online–simply wouldn’t have shown up. How could they have? How would they have known we existed? that the show was happening? Business has never been anything more or less than how we connect with such fantastic people all over the country. It’s how we create shared experiences at shows that become great memories for us and for our listeners. It’s how we connect our art with people who want and appreciate–and sometimes claim to need–it.

Because of all this, I can’t not love business. The alternative is to never have met those people, to never hear their stories or learn their names. The alternative is to play songs for myself and my floorboards, which isn’t what I signed up for. I write to communicate with other human beings, and some level of business/marketing is what’s made that possible.

4. Your Move.

And so I bring this back to you, Writer Out There, who has worried that seeking readers or learning marketing tactics would corrupt your work. And to you, Reader Out There, who has equated marketing with greed or devalued art. A writer can put words on a page all day; words only communicate if someone else sees them. And the desire for communication is, on some level, the precise reason most of us write and read. We want to experience the interchange of experience and information, the play of language between speaker and reader, the new connections that move, educate, bewilder, and sustain us. Business is how we make all that happen.

I’m not saying corruption doesn’t exist. I know that money can buy readers, and that industry gatekeepers are influenced at least as often by a bottom line as by literary merit or humanistic value. I’m aware that publishers generally design their release and marketing strategies to make the most money possible, even if this means excluding intelligent and enthusiastic–yet impoverished–readers. The “Success = Corruption” equation works as a spectre precisely because it’s true much of the time.

But we can’t give into the fear of a corrupting slippery slope. We can’t, for instance, teeter anxiously on the edge of a Facebook status update, worried that if we post something about our work, we’re selling our souls. We can’t loathe business resources or promotional tools, afraid they’ll suck the mystery and life out of art. We don’t need to shun the very tools that get us beyond ourselves, that help us do what we’ve intended all along: communicate. And we don’t have to wonder whether the people with whom we stand to communicate are worth the effort it takes to reach them, AKA business. They are.