The Ploughshares Round-Down: Why “Do What You Love” Is Bad Advice

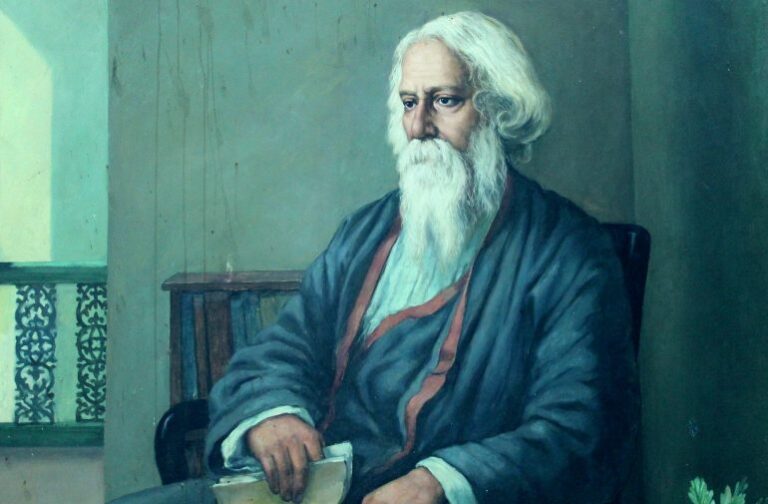

In 2005, Steve Jobs gave a now-famous graduation speech at Stanford University. “You’ve got to find what you love,” he said.

“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.”

“Yes! This is the Truth about careering!” Said everyone, ever.

Or okay, most of us. Who read or heard it.

And who also are privileged enough to have lives in which such an admonition has any chance of being follow-able.

Oh darn.

Alright, so can we have a mass confession? If you’re like me and thousands of others, Jobs’ words resonated like crazy. And so have similar encouragements, from Oprah’s “Live your best life” to like, 90% of all Pinterest pins.

The truth is, this kind of advice is particularly intoxicating to those of us in creative and/or educational fields. We may not be paid well as writers, teachers, musicians, journalists—but damn if we don’t love what we do! We work for love, not money!

Let’s be honest, though: even in love-driven professions, we rarely measure success by the quality of life that results from happily humming along. Instead, we measure it according to publishing deals, tenure, sales, raving reviews. Often, in an effort to reconcile Do what you love to our entrenched success-measures, we tell ourselves that if we haven’t “made it,” we simply haven’t loved enough. Because surely if we just love our work enough, we’ll succeed by some objective standard, right?

…Guys?

In an article in the January issue of Jacobin, author Miya Tokumitsu cautions us to take a step back. Her piece cuts to the heart of what’s wrong with “Do what you love.” Using her work as a springboard, today I’m giving you:

4 Reasons “Do What You Love” is Bad Career Advice for Writers

1. Perhaps most obviously, this advice is unlivable by most of the world’s labor force.

Following it is often an exercise in class privilege. This doesn’t make it wrong, but our enthusiasm for Do What You Love! can blind us to the vast majority of lived experience. In fact, by elevating Work-for-Love, we effectively denigrate the work of most of the world’s laborers, who have no choice but to take a job primarily for the paycheck.

And actually, this includes many of us! Think about it: often, creatives who are totally entranced by the idea of making a living “doing what we love” are also working 2nd and 3rd jobs, primarily for a paycheck. Thus we too are the laborers we denigrate: perceiving jobs that simply pay our bills as embarrassing marks of our failure to make our more “noble” pursuits succeed.

For most of the world, supporting the activities and people we love means laboring in work we don’t. If “Doing What You Love” is accessible only to a small slice of the world’s population, it’s clear: an inability to make our loves pay our bills is not a sign of failure.

2. “Nothing makes exploitation go down easier than convincing workers that they are doing what they love.”

An artist friend of mine had a prestigious job creating art displays for a globally respected clothier. She recalls being told repeatedly, “No one works at [Fabulous Retail Shop] for money. We work here because we love it.” When she was given her latest promotion—along with a 70-hour work week, mass required travel, increased management responsibilities, and a nearly nonexistent raise—she was told again, “You should know by now that no one works for [Exploitative Retail Shop] for money. We work here because we love it.” It took her months to realize she was being eaten alive. She horrified her superiors by walking away.

Unfortunately, many creatives have been in similar positions (ahem: interns, adjuncts, freelancers). By buying into the idea that we should work for love—and that this is more noble than “merely” working for wages—we become exploitable by those who know we want in on a certain profession. We devalue our labor as labor, silencing our rights (and even desires!) to make money from it.

Thus ultimately, even if we DO get to make money from work we “love,” we become engulfed in that labor at the expense of other things we love: relationships, health, hobbies, community, [insert the great thing you never have time to do here].

3. If writers believe that “doing what you love” is a noble pursuit accessible to all, we’ll believe we’re entitled to it if we just commit enough, work enough, love enough.

If our loved work doesn’t turn into a sustainable career, we may think we’ve failed (see #1). But we may also believe that someone’s failed us: maybe editors are all crazy, or the public isn’t smart enough to appreciate our art, or publishers just want more of the same from the same established writers, or no one will give us a chance. These things may at times be true, but also: not everyone can have a career doing what they love. It’s an epic impossibility.

Similarly, if we ARE lucky enough to have such a career, we risk believing that others could do the same if they just work “as hard as we did.” But as Tokumitsu writes,

“[B]eing able to choose a career primarily for personal reward is an unmerited privilege, a sign of that person’s socioeconomic class. Even if a self-employed graphic designer had parents who could pay for art school and cosign a lease for a slick Brooklyn apartment, she can self-righteously bestow [“Do What You Love”] as career advice to those covetous of her success.”

Attaining a writing career isn’t an all-access road. If you’ve “made it,” lending advice to aspiring writers is kind. But also: acknowledge any privileges that gave you a boost. This too is kind.

4. As career advice, “Do What You Love” fails to acknowledge that sometimes, writers have to do difficult, sh*tty, fearsome, WORK.

Like editing. And getting rejected. And feeling painfully awkward while meeting new connections. And editing some more. And being rejected a hundred more times.

Most of us know—at least intellectually—that doing work we “love” requires a lot of work we don’t. But by focusing on “Doing What We Love,” we ignore the sweaty effort necessary to get to those coveted moments of satisfaction, improvement, and/or transcendence. No wonder so many writers expect a first draft to be publishable, or quit after a few rejections. Gritting one’s teeth through a pile of rejection emails or red-penning a 13th draft aren’t fun, lovable, or cuddly activities. They’re work. Although they lead to moments we love, we’d do well to acknowledge that good art isn’t all love, all the time.

What are the Takeaways?

Do what you love is great advice if we interpret it as, “Make sure you make time for the things that matter to you.” If you love writing, make time to write. But please: Do what you love regardless of whether it’s your career.

Because writers, it’s okay to make art that doesn’t contribute to your bottom line. And it’s okay to pay the bills via work that just pays the bills. Meanwhile, make sure you’re also doing what you love.

And do what you don’t love, too: Make yourself edit. Expose yourself to rejection. “Kill your darlings.” If you don’t love doing these things, that’s okay. It’s work. It moves you forward. And it’s worth it.