The Poetry in Footnotes, Endnotes, Annotations, & Bibliographies

As an aspiring young poet with little more guidance than a public library card and a used copy of a Norton anthology, I gravitated to the work of Marianne Moore. Her poems are characterized by extensive use of collage from myriad sources as varied as travel brochures, letters from the electric company, and lines from Henry James. She, like most influences at the beginning of my education, would come to disappoint me as I learned to see the fascist themes and minstrel show tropes that permeate the Modernist canon. It was sad day rereading “An Octopus”—admiring all of its exquisite descriptions and delightful braiding of rhetorical registers through a hodgepodge approach to quotation—and realizing the endeavor was in service of a conservative treatise about the nature of “culture” and “vision.”

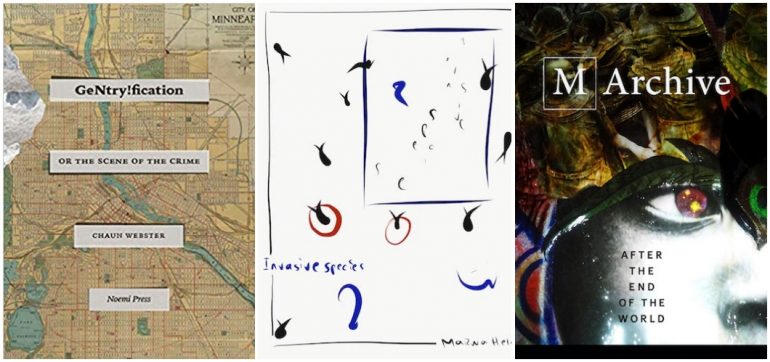

Despite these disappointments, I continue to gravitate to works that draw insight and lyrical energy from snippets and factoids. The abundance of erasure and collage works published in recent years suggests I am not alone in a desire to plumb the archives in search of poetry. Three recent notable poetry collections have drawn upon unlikely source materials—government documents, academic monographs, maps, brochures—to reimagine collage as a vehicle for multiplicity, complexity, and context, instead of that Modernist dream of a singular monolith.

Marwa Helal’s Invasive Species, out this past January, is teeming with examples of how one might discover poetic significance in the fine print of unlikely texts. In this collection, Helal interrogates both the language and the memories associated with documents submitted to and received from the U.S. government in the course of a speaker’s attempts to obtain the permissions necessary to reside as an adult in the country where she was raised and where her parents still live. What might seem at first like a path through tedious bureaucratic paperwork becomes, thanks to Helal’s analyses, augmentations, and translations, a clear and forthright account of cruelties and dehumanizations designed to protect white supremacy and assert imperial power.

At the center of Helal’s book is the abecedarian sequence “Immigration as Second Language,” a dictionary of terms that tells this agonizing story. A is for “aged out” and “asylum”; B is for “birthplace”; C is for “census”—the list goes on. R is for “Returning,” a section of the poem that outlines the cruel choices an immigration system riddled with intentional inefficiencies and blatant racism forces on a family. Helal writes, “Returning to Egypt is hard and doesn’t happen often enough.” In addition to the expense, it is a risk for her and her parents to visit their homeland since it is increasingly the case that return visits can call their immigration status into question—just as such a trip became quite permanent for the speaker. She is forced to make a life for herself in Egypt, with extended family in a country she has had limited opportunities to know. She remarks, “Every time I see my parents while I am in Cairo they seem ages older. I am not used to this much time passing between visits. Six months. Eight months. Nine months in between.”

Helal frequently annotates the speaker’s personal experience with other research to emphasize the ways that individual experiences are connected to a larger political context. In “Returning,” she cites audio obtained by ProPublica from inside a U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility where children are heard wailing. “Border patrol agent jokes, ‘We have an orchestra here.’” O is for “One-800-IMMIGRATION. Payment Plans. Free Consultation.” The poem moves between lines from this advertisement, personal experience, and reporting from The New York Times. After describing personal difficulties, she cuts abruptly to the news. “‘I can’t even begin to picture how we would deport 11 million people in a few years where we don’t have a police state, where the police can’t break down your door at will and take you away without a warrant,’ said Michael Chertoff.”

Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive: After the End of the World, published in 2018, is another work that engages with documents intertextually to create a chorus of voices, none of which are ignored or erased. Often described as an Afrofuturist work, M Archive imagines a future researcher unearthing an archive that reveals how some ancestors evolved beyond the environmental catastrophes, anti-blackness, and capitalist abuses of this present historical moment. The structure of this book is based on a conversation between Gumbs and the scholar M. Jacqui Alexander—every page by Gumbs emerges from a meditation on a line from Alexander’s 2006 Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred. In a form Gumbs describes as “speculative documentary,” the book opens with the imagined archived notebooks of black marine biologists, whose work “suggest[s] that there may be a causal relationship between the bioluminescence in the ocean and the bones of the millions of transatlantic dead. oyeku ogbe.” This is a powerful vision of time and change—Gumbs suggests a vision of history where “any light that you find in the ocean right now cannot be separated from the stolen light of those we long for every morning.” The meditation concludes, “all light is shared with those at the bottom of the ocean,” a line that is annotated and sends readers to page 314 of Alexander’s “Pedagogies of the Sacred.”

Gumbs’s creation of an intertextually collaborative form is reminiscent of the philosopher Sara Ahmed’s assertion that the ideas you use to have other ideas matters. In her 2017 book Living a Feminist Life, Ahmed explicitly cites only women of color, in part to amplify their work and in part to draw attention to how often male scholars have used women’s and biPOC people’s ideas without giving them credit. M Archive imagines a future where salvation comes in the form of unearthing such long-buried work. In the section “Archive of Sky: What We Became,” the researcher discovers a long-lost recording of Audre Lorde. In the company of Lorde’s voice, the researcher “cried during the hours she was in there. she squatted, sweated, moaned. she bled and defecated and urinated and screamed. she scrubbed off layers of her skin,” and at the end of this ordeal she emerges from this womb-like room looking “rather like a baby bird” and “she knew she could fly.” The poems in the book are beautiful expressions of a young scholar coming of age into a full understanding of her own capacities and potentials through a deepening understanding of the wisdom of her ancestors. In this way, Gumb’s book is a powerful allegory for readers, especially Black women and girls, on a similar path.

The book is also a deeply resonate philosophical investigation into the nature of knowledge and memory. M Archive proposes and embodies the idea that the archive, the footnote, the works cited page, the bibliography page, and the work itself all exist for the future. In her poems, Gumbs lifts up and calls attention to all the ideas that called the work into being and must be saved to inspire future work. She writes in “Memory Drive,” that “i knew the ones who would understand wouldn’t be here for three thousand years… and so i decided to write in salt adhered by tears adhered by spit adhered finally by blood.” Moreover, a “Periodic Table of Kitchen Elements” at the back of the book serves as participatory bibliography. Readers are encouraged to understand each section not only as a conversation between Gumbs and Alexander but as an even richer exchange with selected works from a canon of writers, thinkers, and artists that includes Omi Osun, Childish Gambino, Ntozake Shange, and 115 other elemental works that might be hard to recognize if Gumbs wasn’t so mindful to say the names of the people who made her ideas possible.

Chaun Webster’s 2018 collection is another example of poems that critique power structures by diving as deep as possible into the work of citation. GeNtry!fication: Or the Scene of the Crime invents new forms out of his work finding and sharing all relevant scholarly receipts. In this book, which interrogates the history of racist displacement in American cities, generally by focusing on the history of North Minneapolis in particular, Webster asks, footnote by footnote, what it means to live in a country where they have been so many crimes that “no one” committed. For example, the “prologue” section of this book includes a graphic poem where the words “north minneapolis” are repeated dozens of times across the page in overlapping layers of text. The crescendo of repetitions culminates in the last line: “looks a lot like the scene of robbery circa 1492.” Not only is the reminder that U. S. prosperity is rooted in a long history of stolen land and stolen human labor, but Webster’s use of typographic design forces readers to linger over the name of a place, attempting to understand what the repetition is leading to. Likely many readers, numbed by the repetition, will at first gloss over that last line. Such glossing then invites a consideration how such benumbed carelessness might mirror the present-day erasures of indigenous people’s rights on indigenous land as well as the economic rights so often erased by a country built by slave labor.

Much is accomplished on the single page of this poem, but Webster also explores the lyric possibilities of collage via the endnotes in GeNtry!fication. At the back of the book, readers are told, “In the beginning was the northside, and it was a good and layered thing,” clarifying that the layering of the typography mimics the layerings in healthy ecosystems and vibrant human communities. Within this first footnote are further citations: “See Romare Bearden. See James Braxton Peterson,.. See Invisible Man re: in the beginning… there was blackness.” In the second footnote, Webster provides definitions of the word robbery, then reflects on how “our basic assumptions around robbery conceal the biggest heists of the modern world, that modernity itself required such heft.” He annotates further, suggesting readers see James Baldwin, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, and the Wu-Tang Clan. To read a poem by Webster is to read back into a long lineage of ideas that made Webster’s ideas possible.

Another central project of GeNtry!fication is to call attention to certain pervasive racist ideas that make new racist actions and systems possible. In the poem “Astro Colony or an Obscure Rock in the Milkyway will Gentrify also: the scene of the crime,” Webster considers how white supremacy permeates many corners of intellectual life that white people often imagine are separate from racism, such as science and technology. He writes of future displacements, saying, “they will be sent, no doubt for their own good, to this unfamiliar place in the astros. a place decaying but of unique architectural quality.” He writes that on this distant moon, an exploited people will “usher some new sound to shake that little bit of rock until that too becomes a site of forced removal.” The poem is a powerful expression of how long and tiring the fight for justice can be, though in the footnotes Webster writes that the intention is “less nihilism than trying to examine the recurrent text of forced removal and limitations of activist interventions.” He elaborates in a subsequent footnote on Afro-Surrealism reaching for a way to imagine a future that has not already been circumscribed by such injustice.

The ideas we use to have other ideas matters. In new collections by Helal, Gumbs, and Webster we find rich archives of ideas and texts that hold within them visions of a future where people can fly and people can also stay to flourish in the place they call home.