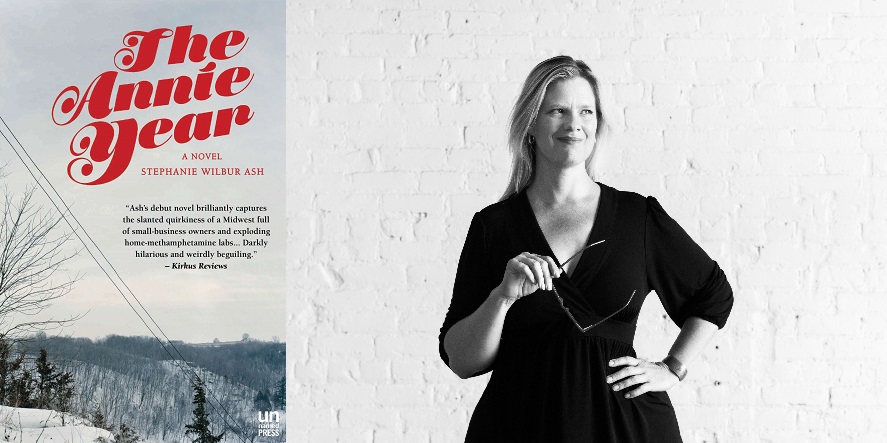

The Push and Pull of the Small Town in The Annie Year

“Every crack in the sidewalk had been there since I could remember,” says The Annie Year‘s narrator Tandy Caide. “Every car in town was in the high school parking lot or waiting in line to get there.”

Tandy’s the CPA in a small town somewhere near Dubuque and the protagonist of Stephanie Wilbur Ash’s debut 2016 novel. Her identity and whole life is shaped by her rural surroundings: She finishes college via correspondence to help take over her father’s accounting business. She marries a man she has no interest in, who thinks buying a cheap hot tub is a romantic gesture, because he’s there and had her father’s approval. And, she turns her world upside down by having an affair with a man whose primary attraction is that he’s a newcomer, an outsider. Something different.

From the start, Ash sets up the town’s population as a defensive fortress, the “us” in “us vs. them.” The plot of the novel does this through the characters’ insular behavior, their obsession with protecting and controlling their own. But more interestingly, the narration itself does this by having Tandy address an unnamed city-dwelling “you,” as in “There was a coffee shop where you could buy the kind of coffee I know people like you are used to.” While part of me felt like it set up a false premise at the beginning of the book—I thought she was going to end up in conversation with someone, à la the framing of Lolita—once I got adjusted, it worked well thematically. Tandy saw the world in terms of the “us” of her town against everyone else; it made sense that she would tell her story with that in mind. The tone rings with a kind of dutiful, proud explanation.

So what’s inside the fortified small town of The Annie Year? The predictability of weekly meetings and knowing everyone you pass by in your day-to-day activities and children doing what their parents expect or else. The intimacy of a man “unbuttoning his pants to make room for the prime rib to move through his system” at a diner booth. Meth-related explosions that both are and aren’t acknowledged by the characters. Relationships that are invasive in both insidious and supportive ways, dragging people down and raising them up. All of small town life has a double edged sword, in fact, like the oft emphasized simplicity. Simplicity allows Tandy pleasure over Mike’s Hard Lemonade and instills a fear of missing out when confronted with the reality of the rest of the world.

Some moments are very familiar: Being unacquainted with the latest and greatest of anything. Settling for the best of bad options in a spouse. The newcomer who is known primarily as his occupation (“the Vo-Ag teacher) and introduced via his ponytail, man clogs, and being called a “hippie elf.” The high school’s theater productions being the cultural epicenter. The very blurry line between gossip and truth and kids throwing rocks at the Country Kitchen sign until it becomes Cunt Itchen. But when Ash has to deal with rural clichéness she generally does so with a graceful, self-aware touch. Tandy’s father says, “Oh, you stupid country kids,” as they watch the high school boys track team, right before expressing his wedding-inducing admiration for the shot put throw of Tandy’s future husband. When Tandy’s asked, “What’s a nice girl doing in a place like this?” she gives the question her full scrutiny, working through to try and divine an answer for herself. The best part about a particular school-related dinner, she decides, is that the school choir doesn’t sing.

Like a lot of small-town protagonists, Tandy has a tolerate-hate relationship with her small town. As a teenager, she wants to “sit alone in a small room and look out the window at a view different from the other windows I had looked out of, or into, the previous seventeen years of my life” and then as an adult she continues to look in those windows and thinks “It looked like the shittiest place on Earth.” In small sections of the book, the “us” of the town becomes a cold “they.” But, like so many characters and so many people, she is tied in ways she can’t fully articulate to her town. It gives her identity; it gives her power. The draw of being exceptional in a “shitty” small town pulls as much weight as being a nobody in the big city. I’ll leave you to guess, or to read, what she chooses.