The Re-Release of Jean Toomer’s Cane

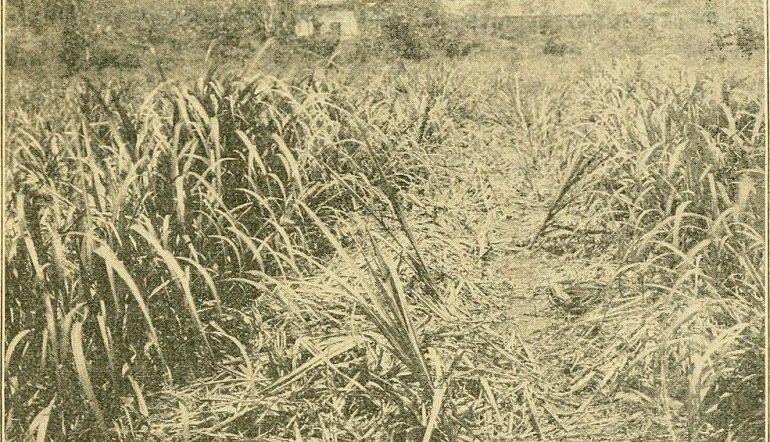

“And all around the air was heavy with the scent of boiling cane.” So begins the second section of “Blood-Burning Moon,” a story of lust, jealousy, and racial violence in the American South that makes up one of the chapters of Jean Toomer’s 1923 modernist masterpiece, Cane. Re-released earlier this year by Penguin Classics with a foreword by What We Lose author Zinzi Clemmons and an introduction by Cornell’s Newton C. Farr Professor of American Culture George Hutchinson, the genre-defying book was met with immediate critical acclaim from both the white literati of 1920s Greenwich Village and the Black intelligentsia in Harlem (where a renaissance was in its early stages). A blend of poetry, drama, and fiction, it depicted African American people in a realistic manner that evaded the tropes and stereotypes that typically accompanied depictions of southern Black life. It showed Black Southerners as powerful, sensual, magnetic personalities unconcerned with and unafraid of white people, refusing to be controlled by the threat of racial violence.

But Toomer’s hesitation to be described as a “Negro writer” has problematized Cane’s place within the history of Black literature. Indeed, the image, from “Blood-Burning Moon,” of cane becoming only more pungent and pervasive after being burned (“The scent of cane came from the copper pan and drenched the forest and the hill that sloped to factory town”) is a fitting metaphor for Toomer’s legacy: the more he tried to distance himself from such labels, the more questions regarding his racial identity came to dominate the conversation around him, both then and now. In their afterword to the 2011 W. W. Norton edition of Cane, the scholars Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Rudolph P. Byrd concluded that shortly after the book’s publication, Toomer became “a Negro who decided to pass for white.” Hutchinson now disagrees, arguing that Toomer was, in fact, exploring a form of resistance to identity, a resistance to tokenization and its twin, commodification. With Penguin’s new edition, released in a time when post-racial fantasies have recently been laid bare as just that—fantasies—we are invited to revisit Cane’s stunning lyricism, a work as experimental and category-defying as its author.

The controversy surrounding Toomer’s identity (was he passing or playing at something more radical—obfuscation?) stems in part from a perturbed letter Toomer wrote to his editor, Horace Liveright, the venerated publisher behind modernist classics like T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. When Liveright wanted to use Toomer’s “Negro” identity to help market the book (despite praise from critics, sales were dismal), Toomer balked at the suggestion. He later became enraged when excerpts from Cane were included in Alain Locke’s famous anthology of African American literature, The New Negro: An Interpretation. Toomer was, throughout his life, inconsistent regarding his racial identity. Census records, draft cards, and personal correspondence show a man who at times claimed to be white and, at others, Black. In a letter to friend and fellow writer Claude McKay, he explained: “Racially, I seem to have seven blood mixtures—French, Dutch, Welsh, Negro, German, Jewish and Indian.”

The fair-skinned Toomer, who was often mistaken for Native American, tried repeatedly to distance himself from the label “Negro writer,” believing he and people like him represented a new race, neither white nor “colored,” but simply “American.” Hutchinson, in his introduction to the new Penguin edition, dissents from Gates Jr.’s and Byrd’s view that Toomer was trying to pass as white. Hutchinson instead insists that Toomer was merely exhausted by the literary establishment’s tendency to pigeonhole Black authors as identity scribes, an exhaustion still felt by writers of color today. “The drama surrounding the publication of Cane,” Hutchinson explains, “epitomizes the fact that no person considered ‘Negro,’ according to the one-drop rule of the United States, could get a hearing except under the sign of blackness, even if they did not consider themselves black.”

Born in 1894, Toomer’s family was part of Washington, D.C.’s Black aristocracy. His maternal grandfather was the esteemed P. B. S. Pinchback; the offspring of a “mulatto” mother and a white planter, Pinchback became governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction, the first African American in the country to hold the office. After a few failed attempts at college, Toomer arrived in New York City in the summer of 1920, like many people since, with a vague aspiration to be a writer. Toomer stood out in New York as someone who was able to successfully co-mingle with the white bohemians of Greenwich Village as well as with the Black artists, writers, and musicians of Harlem. That Toomer was able to conquer this downtown/uptown divide in many ways reflected the writer’s fascination with the indeterminate nature of racial belonging, a fascination that would both mire him in controversy and make him eternally relevant.

In New York, Toomer lacked inspiration (and eventually money). A lucky break came when one of his grandfather’s associates offered him a job as substitute principle of the Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute in Georgia. Though he was just there for a few months, the experience would end up being the most crucial artistic juncture of his professional life. “The experience in Sparta,” Hutchinson writes, “unleashed a steady creative surge.” The culture and geology of Georgia, which introduced Toomer to Negro spirituals, cotton fields, and cane thickets, made an impression, perhaps nowhere better captured than in the poem “Song of the Son,” which appears in the first part of Cane:

O land and soil, red soil and sweet-gum tree,

So scant of grass, so profligate of pines,

Now just before an epoch’s sun declines

Thy son, in time, I have returned to thee,

Thy son, I have in time returned to thee.

In her foreword, Zinzi Clemmons reflects on Toomer’s experimental style and dual participation in the cultural movements of American modernism and the Harlem Renaissance: “Toomer deserves to be considered a respected figure in both.” Clemmons’ own work participates in the tradition of Black experimental writing: her debut novel, What We Lose, has been praised for its unconventional formal structure that blends blog posts, hand-drawn graphs, rap lyrics, and autofiction. Clemmons wrote about her indebtedness to Toomer and Black writers like him in a piece for Lit Hub titled “Where Is Our Black Avant Garde?”

Clemmons also reflects on Toomer’s belief that mixed-race people, who he classed as a new race unto themselves—“Americans”—could serve as healing arbiters between Blacks and whites. Clemmons finds in Toomer’s vision much of what animated the euphoria surrounding the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and the discourse about a “post-racial” America that swiftly followed suit. Looking back on that year from the vantage point of our present political moment, Clemmons remarks, “Today, post-racial feels like a quaint artifact of a more hopeful time.”

The dream, however, that mixed-race children can provide some sort of solution to our racial divisions persists. The April 2018 cover of National Geographic featured two biracial twins on its cover with the promise that they would make us “rethink everything we know about race.” Writing about the cover for New York Magazine, Lauren Michele Jackson remarked, “Rather than confront the power dynamics that racism relies upon to survive, these gestures fuel a deus ex machina fantasy in which humans breed themselves into equality—never mind the fact that mixed-race children have existed for just as long as racism has.” It is precisely this fantasy that vexes critics of Toomer, who admire his undeniable literary gifts but find his fixation with racial transcendence overly metaphysical and worryingly unbothered by the material conditions of anti-blackness.

Cane was Toomer’s last work. Shortly after it was published, he came under the spell of a Russian mystic named George Ivanovich Gurdjieff whose philosophy of spiritual wholeness offered a balm for Toomer’s fragmented and fractured psyche. He spent much of the year following Cane’s publication lecturing on Gurdjieff around Harlem and trying to convince people to study at the mystic’s retreat in Fontainebleau, France. It was at one of these lectures where the poet Langston Hughes first encountered Toomer, an experience Hughes later wrote about in his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea. Reflecting on Cane and the controversy surrounding Toomer’s new ideas about racial identity, Hughes concluded: “Harlem is sorry he stopped writing. He was a fine American writer.”

This piece was originally published on May 30, 2019.