The Repetition and Accretion of Violence

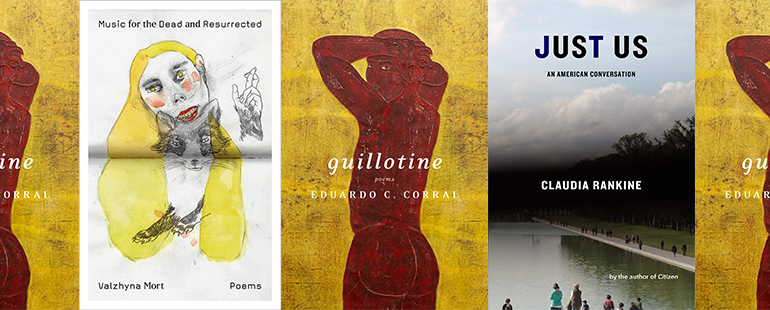

Violence seldom comes in a single dose. A flurry of punches; a rain of gunshots; the irradiated dust that kicks up decades after nuclear disaster. Any schoolyard bully can affirm that violence is most effective when performed repeatedly over time. Three recent books examine state violence by using violence’s signatures—repetition and accretion—as tools within the text. Post-Chernobyl Belarus, barren American border landscapes, and the minefields of everyday social interactions are scrutinized, again and again, in work by poets Valzhyna Mort, Eduardo C. Corral, and Claudia Rankine.

Mort begins Music for the Dead and Resurrected (2020) with references to classic tales (Antigone, The Tempest) as if one must reach deep into Greek mythology to find anything to compare to the devastation of modern Belarus. It isn’t an exaggeration: Belarus was proportionally the hardest hit of all countries during World War II, losing a quarter of its population in the period that included a brutal German occupation; four decades later, it absorbed 70 percent of Chernobyl’s fallout, the final exhale of Soviet rule. These dual inheritances—millions dead, millions living with the ticking clock of radiation—are expressed in Mort’s poems through bones, graves, accordions, and braids, images of the dead and the mutating DNA strands of those who remain: “Here, history comes to an end / like a movie / with rolling credits of headstones, / with nameless credits of mass graves.” Years after these cataclysms, the speaker remains suspicious of a future outside their shadow. Mort pairs abstract homilies with viscerally uncomfortable images to show there is no route out of suffering: “time is supposed to heal / only because once / it was seen with a scalpel in its hands.” How is one to know the difference between a doctor with a scalpel and a man with a blade?

The body is also terrifyingly vulnerable in Corral’s Guillotine (2020). Harm is often self-inflicted, the result of self-hate created by living in a country built on one’s subjugation: “I pinch a mole / on my skin, pull it / off, like a bead— / I pinch & pull until / I am holding / a black rosary.” The rosary, symbol of the colonizing Church, promises salvation but requires self-destruction. The speaker of Corral’s poems is often helpless against harm, whether wrought by the self, by creatures in nightmares, or personified abstractions: “there’s a harmonica tattooed on my collarbone / I can feel death’s mouth on it lips wiry & hot.” As in Mort’s work, the pain of the present is compared to the ancient—specifically, stories in the Bible: “once I tore rain / out of a parable / to strike down / his thirst.” The thirst belongs to the speaker’s son; the impossibility of getting something as necessary as water from religion points to religion’s futility.

Religion requires repetition and accretion: adherents mumble prayers marked by the beads of a rosary, and those adherents must, if the religion is to succeed, multiply. These acts of prayer and expansion are depicted concretely in Corral’s text, as in a poem to Señora de las Sombras, a kind of death saint whose name is repeated over and over, sometimes in collage-y cut-outs, reminiscent of a ransom note. Repetition and accretion are also part of immigration, as people make a journey made by others before. Corral brings the reader to a safehouse for migrants that is revealed to be not safe at all; migrants are forced at bladepoint to call family to beg for ransom money. Cat litter fills a bathtub; the implication is that to avoid giving away the safehouse’s location through a water bill, the migrants must relieve themselves in the litter. In other words, their excrement, rather than being flushed away, builds. Shadowing Corral’s text is Trump’s wall, that other thing built of human refuse.

Just Us (2020) is the implied sequel to Rankine’s genre-forging Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004) and Citizen (2014). Unlike those books, both subtitled “An American Lyric,” Just Us is labeled “An American Conversation.” A lyric expresses a writer’s emotions; a conversation can express the emotions of two or more people, but it can also hide them. In lieu of the heightened images of those previous lyrics, in which a white therapist resembles a Doberman in a reference to white violence carried out by police, Just Us stays closer to the ground, offering the reader a backseat view to conversations that are annotated with footnotes in which the speaker fact-checks herself. In a section titled “liminal spaces ii,” Rankine transcribes actual conversations onto the page, ranging from Lady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson’s meeting with singer Eartha Kitt, a Starbucks employee’s call to a 911 operator, and other scenarios in which white people call on state power to enforce hierarchy. The conversations pile up like a landfill. Rankine uses repetition to underline the performance of white distress while also perversely underlining the stakes for the Black people involved: “Then the black person is asked to leave to vacate to prove to validate to confirm to authorize to legalize their right to be in the air in air in here and then the police help help is called help help the police is called the police help help.” The double “help” is uttered not only by the white claimant, but also by the Black victim.

The footnotes are placed on the left, opposite the main text, so that they burst in black on the white page. They serve one of two purposes, depending on the audience. For the white audience, the footnotes bolster Rankine’s essayistic prose with hard evidence, the unquestionable authority of academia. They are the proof white people require to believe the personal experiences of people of color. For audiences of color, the footnotes recreate their internal monologue—What did I just hear?—as microaggressions stack up. For this audience, subtext matters as much as or even more than text. One footnote, deployed in a passage about a white man in bland khakis who insults his wife in an airport, quietly informs the reader that in the early days, khakis were worn by a Scottish regiment in the Kaffir Wars, the military campaign waged by white settlers in present-day South Africa to drive the Xhosa population farther and farther east; later, the footnote continues, khakis were transformed into civilian garb by World War II veterans. By elevating such marginalia to the level of the main text, Rankine permits the footnotes, bathed in blank space, to function as a kind of poetry. One could imagine another book that consists only of footnotes to an imagined or implied text.

As in her other books, Rankine allows her prose to loosen into verse. Yet verse sometimes feels insufficient to the task of nailing down whiteness: “White portraits on white walls signal ownership of all, / even as white walls white in.” The lines follow a dense page of footnotes that tie the dominant white cube aesthetic of today’s art galleries to the Nazis, employing long quotes sweeping across twentieth-century history; the lines look flimsy next to the bulky references. Here, Rankine reveals the limits of the lyric—the mode obsessed with the personal, rather than the structural. Implied is an uncomfortable question for anyone who has picked up a pen in the hope something important might spill out: how much can literature change the world when the raw facts are already so powerful?

The American conversation, it turns out, is less between the speaker and her interlocutors than it is between the speaker and herself. The speaker is self-aware of her ruminative nature, indulging in it even as she questions it: “sometimes I become caught by the idea that repetition occurs if the wheels keep spinning. Repetition is insistence and one can collude only so much. Sometimes I just want to throw myself inside the gears. Sometimes, as James Baldwin said, I want to change one word or a single sentence.” That one change—an echo of the word help, the writing of the word white—brings the reader a little closer to escape.

This piece was originally published on February 25, 2021.