The Soul of a City with No Soul

Many writers attempt, either through emotional impulse or intellectual exercise, to capture the soul of a place in their work. Ben Lerner returns again and again to Topeka, Kansas; Joshua Mohr’s characters primarily haunt the underbelly dives of San Francisco; and in Lauren Francis-Sharma’s novels, she leads readers through the island heat of Trinidad both past and present. But what if a place is known popularly for having no soul? How then to capture its true essence?

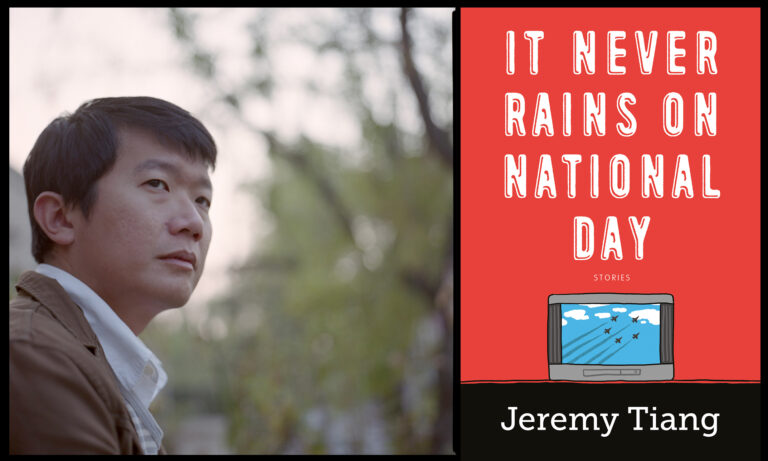

Dario Diofebi seeks to answer this in his debut novel, Paradise, Nevada, out this week, a sprawling Tolstoy-ian drama set in the gaming pits and shadowy clubs of Las Vegas, a city dedicated to artifice, imitation, and fantasy, a city the author reminds us wasn’t built on winners. Paradise, Nevada is an ambitious novel that is partly a love letter to Las Vegas, and partly a bleak and honest depiction of an area that is rapidly gentrifying, leaving behind longtime residents and workers. And like the novels of Tolstoy and other Russian masters, it attempts to answer a litany of weighty and pressing questions: How should a person be? What is America under late-stage capitalism? And how are human beings warped by the incentives of our modern economy—money, clicks, and followers?

The novel centers on the lives of Ray, a poker player; Mary Ann, a cocktail waitress; Lindsay, a newspaper reporter; and Tom, another poker player, though a rather unwitting one who, like the author, is a transplant from Italy. With the exception of Lindsay, they have all come to Las Vegas from elsewhere, each seeking opportunity, yes, but, more importantly, each preoccupied with how they should live in the world. Ray is an online poker player frustrated by his humanity, his statistical variance, his inability to play the game with the precision of a computer. Mary Ann would similarly like to feel less human and spends much of the novel striving for some unattainable transcendence of all selfish desire. Part of the joy of the novel is watching how Las Vegas punishes or rewards the characters, how it helps or hinders them on their individual journeys. Las Vegas is not the first place that comes to my mind as a setting for personal growth, and yet it is a moral crisis at the high stakes poker table that shows Ray how deeply and wonderfully human he is, and it is through the hospitality workers’ union that Mary Ann is able to achieve a modicum of the selflessness that she craves.

Lindsay is an interesting foil among the cast. She is a life-long Nevadan as well as a Mormon, and we learn some of the history of Mormon influence in the state. This detour—one of many—provides ballast as Diofebi attempts to capture the city by giving readers a 360-degree view, a panoramic sweep that encompasses the casinos, the apartment buildings, the hipsters, the drug dealers, the desert, the past, and the future. The chapters bounce from one character to another, with interludes set into the narrative to provide backstory on the gentrification of the city’s East Fremont neighborhood, the influence of Silicon Valley investors, and Howard Hughes’s contested will. Diofebi also pauses the story to tell the tale of the fictional Positano casino wherein much of the novel’s action takes place. The Positano is worth mentioning because, aside from being a luxury casino resort, it is a fully loaded metaphor for the unreality of Las Vegas, a city that often feels, in these pages, as though it is perpetually a row of false-front saloons, always wanting to appear bigger and grander than it is. The Positano is a recreation of an entire Italian seaside village complete with hills, caves, and a Strip-side rolling ocean. The particularly ’90s Las Vegas obsession with importing famous world landmarks in miniature is remarked on in perfect deadpan when Diofebi says interest in such kitsch died with the dawn of the new millennium: “But alas, tempus fugit . . . Never again would a $3 billion rock-and-salt-water cultural appropriation be green-lit by investors.”

The collision between Italy and America is sounded repeatedly in the novel, and some of Diofebi’s most beautiful writing happens when he meditates on poker player Tom’s former life in the shabby Roman suburbs. “Every Italian has a personal America,” he writes. “America is to an Italian at best an act of translation, shapeless and patched together over time by television, music, and distant uncles . . . There isn’t a single Italian who doesn’t hold a strong idea of what America is, an intense idiosyncratic relationship with the strange far-off land Italy remains compelled to measure itself against.” It would be reductive to call Paradise, Nevada an immigrant novel, though almost every character is an immigrant, each with their own personal Las Vegas cobbled together in their imagination. There isn’t a single American who doesn’t hold a strong idea of what Las Vegas is, and I believe part of Diofebi’s undertaking in this novel was to show not only the soul of the city, but all the ways in which Las Vegas is imagined in the American consciousness. It is as though Diofebi dropped a dome on the city and meticulously cataloged all that he found. Tolstoy similarly set himself the task of capturing an entire world in his narratives.

To call Paradise, Nevada, then, a poker novel, or a thriller, or a bildungsroman, or a critique of the information economy, while all true, would miss so much. It is a novel that contains multitudes, with characters and places and history and future living inside the pages like Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional infinite tome from his short story “The Book of Sand.” Each character seems to contain more characters within; each location—Paris, Las Vegas, or a fictional recreation of the Shibuya crossing—functions in triplicate as character, metaphor, and critique. In order to capture something so elusive and grand as the soul of a city, perhaps this has to be the case. Or perhaps, because Las Vegas is the blinking, gyrating fantasy that it is, nothing can be taken for what it seems and everything must stand in for a larger idea. A half-scale model of the Eiffel Tower is either the low point of American mediocrity or a spectacularly maximalist homage, depending on who you ask. Diofebi presents both arguments in his novel, with the truth resting a foot on each side.

Ray, Mary Ann, Lindsay, and Tom likewise don’t so much converge as brush against one another on the Strip, their storylines gathering speed like parallel trains racing toward the same station, the completion of an arc that the opening lines of the novel promise will be both “extraordinary and dull. Dazzling and quotidian.” Perhaps this is the soul of the city that Diofebi has set out to capture: the neon and the fountains and the glitter and the feathers are at once everything and nothing. They are all you see until you look long enough. Over time everything fades into abstraction. Seen every day, even the extraordinary becomes ordinary. An explosion is introduced in the prologue, though even this fades into the background of the reader’s imagination, replaced over hundreds of pages with mountains of glistening buffet shrimp, exotic dancers suspended upside down in elaborate costume, and the heart-quickening thrill of holding pocket aces. Las Vegas is a feat of tremendous sleight of hand. What Diofebi shows in his debut is all the thousands of machinations happening in the background, producing what is ultimately a glorious illusion.