The Subversive Gyneceum of Hotel du Lac

Thanks to the jacket copy, a generation of readers has been primed to read Anita Brookner’s 1984 Booker Prize-winning novel Hotel du Lac as “potently subversive.” Subversive how? The headline of Anne Tyler’s contemporaneous New York Times review offers one answer: “A Solitary Life is Still Worth Living.” Edith Hope, the novel’s heroine, jilts a fiancé, rejects a new proposal, and ends her affair with her married lover. Plenty to consider subversive in a context that must append the word “still” to the assertion of a single woman’s worth.

All the attention critics give to Brookner’s unmarried heroines, though, obscures what’s truly subversive in Hotel du Lac. It isn’t just that Edith charts a different course, maritally speaking; it’s that the novel’s dramatic focus is women looking critically at other women—something that occurs because Brookner has consciously placed her characters in a “gyneceum.”

I first picked up the novel because my writing group—all of us MFAers who’ve met for ten years post-program—wanted to read a book none of us knew. We discovered more complexity than we expected from the slim 184 pages, and the more I learned about Anita Brookner, the more surprised I felt that I’d missed her for so long. The cult of Brookner fans ranges from writers like Julian Barnes to academics like Ann Fisher-Wirth, who confesses to a love/hate relationship with Brookner’s novels. Complexity is synonymous with Brookner; even in interviews, she maintains a wit so dry and subtle, you would never realize she was wielding a dart until it was lodged under your skin.

It’s in these sly hands that Hotel du Lac begins with Edith, a writer of romance novels, arriving at an old-fashioned hotel for a penitential exile forced upon her by her friends in the wake of perceived misbehavior. Brookner withholds the details of the misbehavior until we have come to know the off-season hotel and its inmates, thereby diverting our conventional interest in plot (why is Edith here?) as we fall into the novel’s main action: the day-to-day interactions of the almost exclusively female guests.

Edith is none too thrilled to find herself among, as she puts it, “women, women, only women”: the charming Mrs. Pusey and her doting daughter, Jennifer; the beautiful, rail-thin Monica; and the elderly “pug-faced lady,” Mme de Bonneuil. But she nonetheless studies the other women, her first impressions turning into deeper acquaintance, which in turn changes her impressions.

We see this first with the Puseys. Mrs. Pusey commands attention through her expensive clothing and flirtatious, confident manner. Jennifer is “a rather paler version of her mother,” but Edith, in watching them enjoy one another’s company, is “aware of powerful and undiagnosed feelings toward these two: curiosity, envy, delight, attraction, and fear, the fear she always felt in the presence of strong personalities.” At first, Edith “joyfully” accepts when the Puseys invite her to join their table. Over time, though, she finds their conversation one-sided and their tastes purely material; their obliviousness to others is exemplified by Mrs. Pusey’s not even hearing Edith likening herself to Virginia Woolf, instead exclaiming she’s just like Princess Anne. In so doing, she mistakes the quiet, serious writer that Edith actually is and recasts her in privileged terms they can understand, placing Edith squarely in the entourage to their own highnesses.

Ready, then, to distance herself from the Puseys, Edith falls in with the enigmatic Monica. Monica’s eager gossip suggests she, too, has been busy forming opinions of the other women. She mocks the Puseys’ obsessive shopping and lightly pities the “poor old trout” Mme de Bonneuil, whose son has installed her at the hotel because his wife doesn’t want her in the house. As Edith and Monica begin going on shopping and coffee outings, we learn that Monica’s husband sent her to the hotel under threat of divorce if she doesn’t recover from her eating disorder enough to bear him an heir. Edith recognizes Monica’s sad state, but she still inwardly critiques what Monica offers: “It was not, in fact, much to [Edith’s] taste to spend so much time talking about clothes or calculating other women’s incomes or chances: such discussions had always seemed to her to be of intrinsically poor quality.” She considers Monica “over-bred” and detects an element of entitlement in her need for “a female attendant, a meek and complaisant foil, in whom she could confide, and whose opinion she could afford to discount.” Edith resists playing this role, just as she evades the Puseys’ entourage.

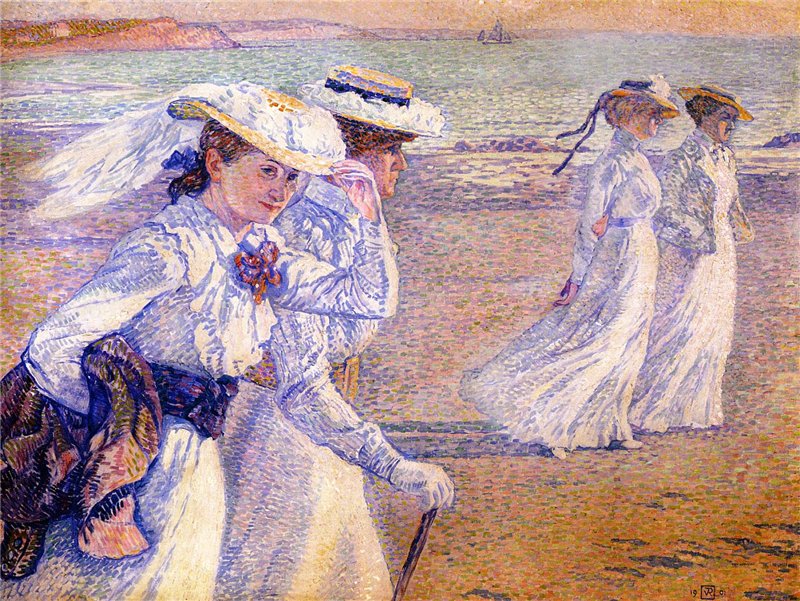

The intimate revealing of these women takes time, and even Edith grows impatient, noting one evening when the dining room is busy that “it was agreeable to see men, after days in this gyneceum, bringing the place to life.” But however stagnant the “gyneceum”—or, in its classical sense, women’s quarters—may at times feel, we see flashes of the other women relating to one another in characterizing ways. Monica and Mrs. Pusey eagerly exchange notes on dressmakers, even though Mrs. Pusey “hated Monica, in whom she sensed both opposition and failure.” Jennifer offers a “cheerful but steady refusal of any kind of mutuality” with Edith or Monica, even though she’s their same age; instead, she’s so subsumed by her mother that she remains in a perpetual adolescent state despite being almost 40. Mme de Bonneuil’s quiet, “entirely correct” presence is its own subtle relating to the chatter and shopping frenzy of the women around her, as is her “Toujours pomponnée?” (Always dolled-up?) sotto voce comment on Mrs. Pusey.

That the gyneceum offers no easy community is already apparent, but perhaps nowhere does this so crystallize as in the scene where Edith, at last, speaks her impressions aloud. It starts with her taking a walk to escape frustration over a small but overblown incident with the Puseys. She blames the situation on the guests being “so many women,” and it’s partly those women she’s trying to escape. But when she stops for coffee, she runs into a brooding Monica. When Edith politely asks about Monica’s plans for the day, Monica rails that she never has plans and adds, “You sometimes strike me as a bit thick.” The conversation continues until Edith at last articulates her opinion of the Puseys:

I dread such women’s attempts to recruit me, to make me their accomplice. I’m not talking about the feminists. I can understand their position, although I’m not all that sympathetic to it. I’m talking about the ultra-feminine. I’m talking about the complacent consumers of men with their complicated but unwritten rules of what is due to them. Treats. Indulgences. Privileges. The right to make illogical fusses. The cult of themselves. Such women strike me as dishonourable. And terrifying.

Although we’ve watched Edith position herself in relation to the Puseys and Monica, this is the first she speaks out, and she delivers a sharp manifesto triangulating among the feminists, the ultra-feminine, and (tacitly) her own type, which she elsewhere compares to an Aesop tortoise against the hares. Ironically, Monica, who a page before called Edith thick, responds, “Above my head, I’m afraid.” In yet another ironic twist, Edith and Monica have finally found a sense of camaraderie as they leave the café together, full of a sense that they’re equally caught in their own unsolvable lives…only to see the Puseys emerging from a shop up the street. Neither wants to encounter the Puseys, so they retreat to the café for another cup of coffee—where the Puseys themselves soon arrive for their own refreshment.

This is precisely the kind of layered scene that gives this book its heft—everything from the content of the conversation to the physical positioning of the characters to the shifting feelings that color a wasted day is significant. There’s even an attempt at community when Edith, arm-in-arm with Monica reflects, “Women share their sadness”—although what she means by “sharing” isn’t compassion but instead the sense of a common trait. The women look at each other; they affect one another’s trajectory; they fail to hear one another; and, ultimately, they get nowhere. But because of this, their relationships come through the page as very real.

Notably, we can’t say the same of Brookner’s men. She handles the key moments of Edith’s journey to confirmed singlehood in offstage or passing ways: the jilting of her fiancé, Geoffrey, is presented as a late flashback, and the repudiation of Mr. Neville’s marriage proposal and the ending of her one love affair occur in the final pages as almost an epiphanic punchline. Compared to the nuanced portrayal of the women, Geoffrey and paramour David are shadowy references, and while Mr. Neville is on stage during Edith’s time at the hotel, he mostly surfaces to speak his self-serving philosophy. If Brookner’s main subversive point was a heroine who remains single, the focus would fall more to these dramatic relationships. But instead, as we have seen, the meat of the novel is with women who have little to do in a near-empty hotel. Putting the action here stakes a claim for relationships between women as the primary subject—and pushes the novel into subversive territory.

Virginia Woolf, whom Brookner invokes several times in relation to Edith, observes in A Room of One’s Own that portrayals of women’s relationships in fiction have historically been “too simple. So much has been left out, unattempted. . . . Almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men.” Although this passage is never quoted in Hotel du Lac, it helps us understand just how subversive—and smart—Brookner’s gyneceum is: she plucks the women from lives where they’re seen only in relation to men (singleton Edith, widowed Mrs. Pusey, failing Monica, superfluous Mme de Bonneuil) and places them where they have the freedom to interact in close, nuanced ways. To do this in fiction subverts conventional depictions of women.

If it’s tempting to downplay the achievement by pointing to Woolf’s observation as being nearly a century old, consider how relevant we contemporary readers and consumers of media find the Bechdel test. The Bechdel test underscores the lack of women’s representation by asking—almost absurdly—whether a work has two women characters who have a conversation about something other than a man. According to Allison Bechdel, who popularized it, the test has roots in Virginia Woolf’s ideas and first appeared in Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip—only a year after Hotel du Lac’s publication. In other words, the struggle to find nuanced representation of women characters outside their relation to men is contemporary both to the novel’s publication and to our own Bechdel-test vernacular, three decades later.

Fisher-Wirth, in her essay “Hunger Art: The Novels of Anita Brookner,” argues that characters across Brookner’s oeuvre have internalized patriarchal values and desire to be part of a system that excludes them. To be sure, Brookner isn’t out to win victories for feminism; Edith criticizes feminists and plainly isn’t one. Neither do the other women have much occupation beyond shopping and minute occurrences. Perhaps Brookner’s own comment in a 1984 BBC interview best summarizes what she offers in Hotel du Lac: “I don’t think it helps to politicize women because they are so various.” There is no political victory here; there is no version of womanhood set forth to rally around, nor even an attempt at a role model. But the degree to which Brookner gives her women characters space to look at one another and do so critically makes the novel a significant invitation for women to observe our own counterparts and to claim room for considering what we are and what we are not.