The Tale of Genji, Suspended Between East and West

The Tale of Genji is the story of a handsome prince, his numerous complicated love affairs, and the world of palaces and moonlit gardens through which he wanders, playing the bamboo flute and writing poetry. But Genji is also much more than that: it is the world’s first novel; a central force in Japanese culture; and most of all, an enduring emblem of Japaneseness, the sometimes maddeningly hard-to-define essence of what it is to be Japanese. We in the English-speaking world are used to the idea that we apprehend Genji only dimly through translation, as if through a scrim, watching shadows. So why then have two Japanese sisters, both well-known poets, spent years retranslating an Edwardian English translation of the novel back into Japanese? And why has it been a smash hit in Japan? The answer is complicated, entwined with the elusive nature of Genji itself, a book that seems to be everywhere in Japanese culture and yet always out of reach.

The place to begin is the novel’s origin, including the instability of the text and its author’s identity. Completed early in the 11th century, Genji is a product of late Heian court life, a period when the aristocratic world of the capital was at its tipping point, soon to be eclipsed by the samurai clans from the provinces. The novel is thus something of an elegy, the final flowering of a culture already dimly aware that its time might be passing. Its author was a minor aristocrat, a lady-in-waiting in service to the Empress Sôshi named Murasaki Shikibu. That’s a nickname—Murasaki is in fact the novel’s much-beloved heroine, and Shikibu the author’s father’s court rank; her real name remains unknown, as do her birth and death dates. What we can say is that she wrote at a time before the printing press, when books were copied out by hand and circulated among friends, and literacy was largely limited to the court and the priesthood—a small, self-enclosed, self-referential audience. Genji was thus less a novel in the modern sense than a kind of ongoing literary performance piece, written over a decade, with chapters circulating as they were produced. The novel’s final shape was never a priority: we know that Murasaki Shikibu personally oversaw the collation of at least three different versions of the book, and that alternative versions were also being passed around, some including apocryphal chapters added by readers—ancient fan fiction. There is also a longstanding tradition, usually discounted by modern scholars, that Murasaki Shikibu died before completing the novel, and that it was finished by her daughter, the poet Daini no Sanmi. Whoever wrote the last chapters, they show a marked darkening of sensibility—a fully disillusioned take on the theme of desire.

But Genji’s elusive quality is really a matter of language. The novel is written in a courtly version of the vernacular of its day: grammatically complex, exquisitely attuned to the finest gradations of rank and relationship, a hyper-sensitive Geiger counter recording shifting levels of mutual awareness. It is horrified by the gaucherie of direct statement, preferring hint and implication, equivocation, the layering of nuance. And it draws power from a densely populated universe of reference, ranging from the poetry of the Imperial anthologies to court ritual and dress, etiquette and architecture. But within just a couple of hundred years, many of those references had become impossible to decipher, important vocabulary lost, whole passages turned opaque. Even as literacy spread to the samurai and merchant classes, reading the novel remained an attainment of the highly educated, who depended on a metastasizing commentarial tradition to make sense of what they were reading. By the 19th century, the gap between contemporary Japanese and the language of Genji had grown so wide that it was really a chasm with only a rickety rope bridge stretched across.

That was the situation when Japan was forced open to the West by U.S. gunboats in 1853 and pushed against its will into the modern world. As Japanese intellectuals began learning English and reading the literature of the West, they were soon faced with a quandary: Was Genji an example of Japan’s cultural richness or its backwardness? Was it something to hold onto or abandon? And why did it feel so strangely foreign—more foreign, in a way, than Dostoyevsky? Murasaki Shikibu’s masterpiece became a cultural flashpoint, with Japanese writers coming down pro or con. On the pro side, the poet Yosano Akiko created the first modern Japanese edition of the novel, translating Murasaki’s prose into contemporary Japanese. She rewrote with impunity—cutting, summarizing, reorganizing—but for the first time, ordinary readers had access to a story they had previously known only through the theater and woodblock prints.

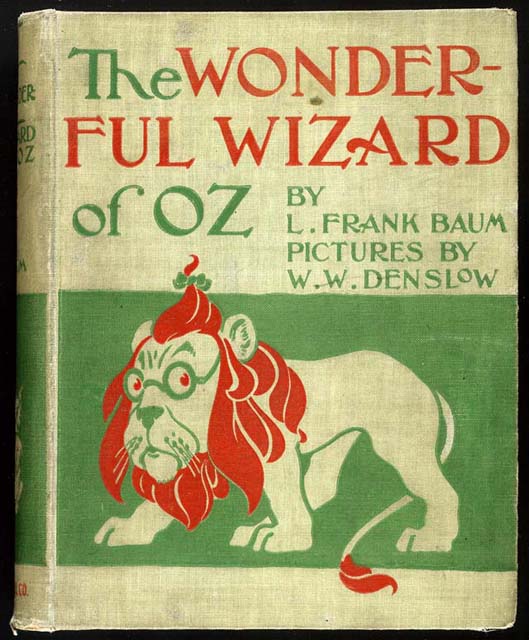

Perhaps it helped that Genji was also garnering attention in the West. The first translation, by Suematsu Kenchô in 1882, was only partial, its prose marred by a flowery Victorianism that was already going out of style. The real breakthrough was the six-volume edition by the British linguist Arthur Waley, the first part of which came out in 1925. Virginia Woolf, who reviewed the book in British Vogue, was delighted by the author’s “hatred of bombast, her humor, her common sense, her passion for the contrasts and curiosities of human nature, for old houses moldering away among the weeds and the winds.” She seized on Murasaki Shikibu as a progenitor of the modern feminist novelist, focused not on male stories of politics and war but on ordinary life in all its emotional complexity. Other reviewers soon chimed in, citing Genji’s psychological acuity, its eye for beauty, its deep understanding of the relationship between desire and loss.

What these writers couldn’t know was how drastically Waley had tailored the original to his audience. Like Akiko on the Japanese scene, he recast Murasaki’s novel with a breezy sense of freedom, cutting, paraphrasing, and rewriting. His attitude toward questions of authenticity can seem almost blithe by today’s standards. “When translating prose dialogue,” he explained in 1958, “one ought to make the characters say things that people talking English could conceivably say. One ought to hear them talking, just as a novelist hears his characters talk.” But Waley’s translation is saved by his deep grasp of Murasaki’s worldview, and his intuitive sense of how to use the tools of the modern novel to achieve her ancient goals. His Genji is intimate and chatty, shifting back and forth in tone between the Edwardian novel of manners and something more like a fairy tale. The combination works: by the time the last volume came out in 1933, Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th century tale was no longer just the central repository of the Japanese sensibility—it had been enshrined as one of the world’s great novels too.

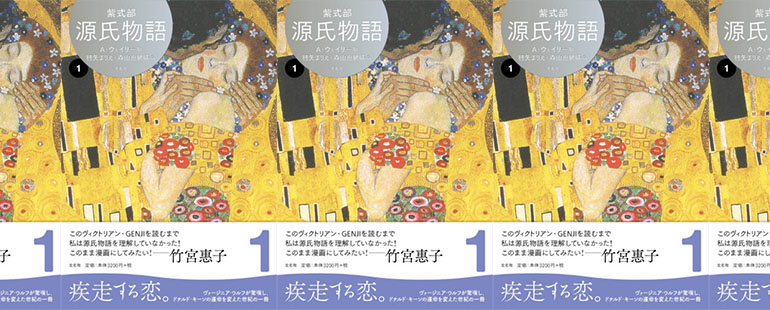

Genji’s status as a work of world literature is the last piece of the puzzle, the context we need in order to loop back to the beginning of our story. In 2017, two Japanese sisters, the poets Mariya Marié and Moriyama Megumi, published the first installment of a new modern Japanese translation of the novel, with the fourth and last volume appearing in 2019. This isn’t in itself all that surprising: since Yosano Akiko’s edition, there have been over forty such modern translations, with one prominent Japanese novelist after another trying to recast Genji for a new generation. The difference is that, in a sort of postmodernist twist, Mariya and Moriyama didn’t translate Murasaki’s original into modern Japanese—they retranslated Waley’s English-language translation of that original.

The Mariya-Moriyama books’ physical presentation capitalizes on the international angle without ever addressing its sheer strangeness. “The book that made Virginia Woolf wonder in admiration,” says the marketing copy on a paper band around the first volume. Above that, on the jacket itself, is a blurb from graphic novelist Takemiya Mieko: “I never understood Genji Monogatari until I read this Victorian Genji! I want to take it and turn it into a manga!” Instead of the usual cover art from the 12th century Genji Emaki scroll, full of round-faced Heian courtiers in almost architectural kimono, the illustration is Gustave Klimt’s 1908 “The Kiss,” a work of passionate Japonism, glittering with decorative gold leaf and fin de siècle European glamour.

The questions that arise here form a hall of mirrors in which it’s easy to get lost. Why would a Japanese reader want to experience the central novel of his or her tradition filtered through an Edwardian English translation? Is this new Genji an abject capitulation to the cultural authority of the West? Or is it the opposite, a bold act of reverse-appropriation? Or could it be a third and altogether much stranger thing: the product of a new global literature in which issues of origin and authenticity are irrelevant? To complicate matters even further, Mariya and Moriyama tend to treat all of these problems as beside the point. Their goal, they say, “Is to simply show that Waley’s Genji, though a translation, is in itself a splendid work of literature.”

What is the truth here? From the very first page of the Mariya-Moriyama translation, the familiar story of the Shining Prince feels ever-so-slightly, ever-so-pleasurably defamiliarized, as if we are looking at it through an odd sort of cultural double exposure. That effect begins with the book’s orthography, no small thing in a language that uses Chinese characters and two different forms of syllabic notation, as well as the Roman alphabet, to express meaning. We see it first on the title page, which places the Japanese title源氏物語 next to Waley’s The Tale of Genji— Lady Murasaki’s Masterpiece, and watch as it continues into the chapter headings (夢浮橋The Bridge of Dreams). The effect is primarily visual, but nevertheless real. More substantive is the translators’ decision to keep many of Waley’s names and court titles in English, spelling them out in katakana, the syllabary reserved for approximating the sound of foreign words. Thus, our protagonist, 光源氏, (Hikaru Genji) is now known as シャイニング・プリンス (shainingu purinsu,) and the book’s heroine, 紫の上 (Murasaki no Ue) as レディ・ムラサキ (redi murasaki, Lady Murasaki). Together, they inhabit an Imperial court where the emperor is referred to as enpera and the imperial servants by British-sounding titles such as wadorobu no redi, Lady of the Wardrobe, and beddochenba no redi, Lady of the Bedchamber. The effect is to stress the idea that we are reading something foreign.

There is something foreign in the clarity of the prose as well. Suddenly, Genji is relatively easy to read, even for this amateur linguist—direct and explicit, while other versions tend to be indirect and serpentine in the manner of the original. There’s less guesswork involved too, as Waley’s editorial insertions help illuminate the mysteries of palace architecture and ceremony. And the pace is definitely faster, the action more focused. One reason is all the cutting and summarizing that he did, but another is that many of the poems that dot the original are deftly incorporated into the prose itself, eliminating the need to slow down as one moves back and forth between those two different modes of understanding (a process that was a natural part of Murasaki’s reading experience, but not ours).

But is it Genji? Maybe it’s time to stop worrying about that question and replace it with other, more productive questions. For example, what does it say about the very idea of authenticity that instead of the real Genji we find ourselves sorting through ever-multiplying acts of representation—“Genjis”? And what does it mean that we continue to try each new representation, expecting, in spite of ourselves, that the real Genji will finally appear? Do we continue to love Genji because it reflects back that yearning over the span of two thousand years? Volume One of the Mariya-Moriyama translation begins with an epigraph from “Sleeping Beauty,” poignant in its sense of belatedness: Is that you, Prince? she asked. I’ve been waiting such a very long time.