The Things We Find in Books

Whatever the reasons for Borders going out of business, it sure wasn’t for lack of sturdy, long-lasting bookmarks.

Let me explain. Recently, I picked up my wife’s copy of Phillip Roth’s The Plot Against America, after eying it on our bookshelf for a couple of years. After finally giving in, I fell quickly into Roth’s labyrinthine sentences and pointed cultural commentaries. And then, after a night or two of before-bed reading, I noticed that the bookmark I’d been using was from the Borders Bookstore in Schaumburg, Illinois.

This was odd, as I’m sure my wife has never been to the Borders in Schaumburg, Illinois—which, like all of its kind, was closed when the company went of belly-up in 2011. But more importantly, even I had not been to this particular bookstore in more than fifteen years.

This bookstore was a hangout for my pals and me, post-high school. A friend worked in the café, and often slipped me free spinach-and-feta pies from the pastry case. There was always a healthy assortment of suburban teens, floundering college students, and vaguely crazy people inhabiting that café. And I was one of the many who fit somewhere between those categories.

I bought more than a few books there in those days, and as a result was in possession of a surfeit of these bookmarks. Like most people, I’ll use just about anything to hold my page: receipts, price tags, flyers, old photos, pieces of mail, greeting cards. Anything, that is, except a blank piece of paper. It isn’t rational, but to me a strip of printer or notebook paper gives a book a limp and sickly look. It makes the book look unloved. I think a bookmark represents more than just its use. It adds something to the experience of reading.

Chances are this particular Borders bookmark had been nestled within various books in my—and then our—humble library ever since. At some point, when my wife last read the Roth novel, she must have retrieved it from some other book on the shelf. Or perhaps I had started the book and not finished it, and I’d just forgotten. Either way, from now on that Roth novel will be linked in my mind with these people and times from my own past.

Likewise, when my position at the literary journal Gulf Coast ended last year, I left with a handful of bookmarks emblazoned with the design of the first issue that my co-editor and I worked on. These are now scattered through my shelves, more than a thousand miles away from our cramped and crowded office. When I pick up a book and pull that marker from its pages, though, I am for a split second taken back to those hectic, heady days.

I enjoy happening on other people’s bookmarks, too. On one of my recent pilgrimages to Duttenhofer’s, a sprawling, dusty old used bookstore near the University of Cincinnati campus, I picked up two books and found in each of them artifacts from their previous readers. As it happened, both books—one a Paul Theroux novel, the other a French-language Jean Giono volume—contained souvenirs from France. The Giono book housed a ticket to the Musee des Beaux Arts in Rouen, while the Theroux book contained two slips of paper: a card-stock advertisement for a vineyard, and a label carefully pulled from a bottle of wine. I’ve since been tempted to track down a bottle of this vintage, to taste what the previous owner of this book was possibly tasting while reading.

I’m not alone in my bookmark fascination, either. There are a couple of websites devoted to the stuff found in used books, perhaps the most extensive of which is Forgotten Bookmarks. Posted without commentary, the owner of a used bookstore simply offers images of his findings, along with the books where they were hidden. And then there’s Found Magazine, devoted to notes and drawings and other evidences of strangers’ inner and outer lives. Many of these notes are discovered in books, and to me, of course, these are the most interesting.

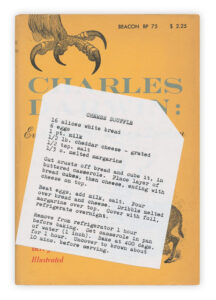

I think it’s the juxtaposition of the marker and the book that has so much potential to fascinate. Anyone can read a compilation of writings by Charles Darwin, but who reads that while also grappling with a difficult cheese soufflé? Many people have read Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, but who also writes a note to her or his special man with a “wounded heart”? (Or did the wounded man read Atwood?)

Just one of those objects—the book or the marker—would be a point on a graph, but with both, we have a line; the beginnings, perhaps, of a picture. Suddenly, from these two simple objects, we start to see characters and story.