The Wild Fox of Yemen by Threa Almontaser

The Wild Fox of Yemen

Threa Almontaser

Graywolf Press | April 6, 2021

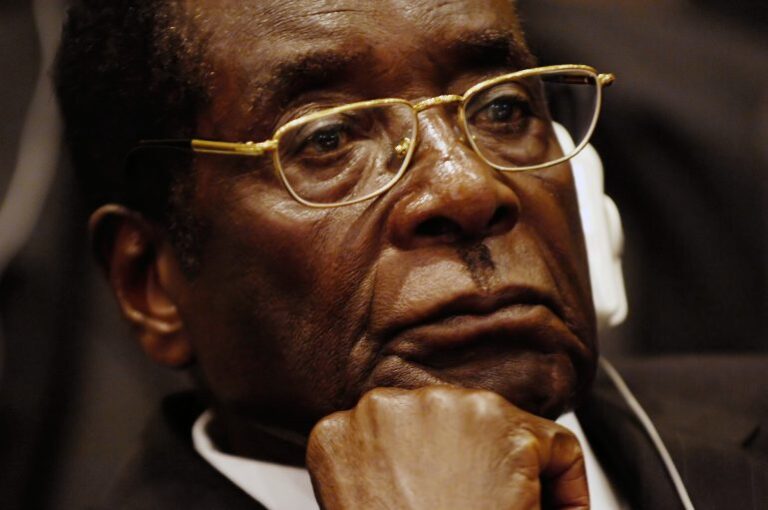

Threa Almontaser’s The Wild Fox of Yemen is a vast and celebratory exploration of language, family, and diasporic identity. Recipient of the Academy of American Poets’ Walt Whitman Award for best first book in 2020, the collection ranges from the intimately personal to the searingly political. Almontaser, who is Yemeni American and was born and raised in New York City, invokes both the experience of being a young, Arab, Muslim woman in 21st century America and a portrait of Yemen that rebukes Western stereotypes of the place and its people.

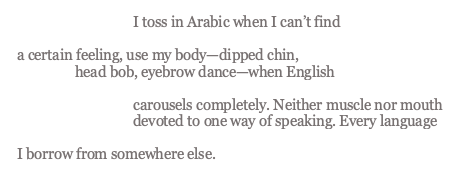

The primary way the collection accomplishes this is through Almontaser’s close focus on language. These poems are concerned with its fragilities and limitations of language: how language can be lost, how language can be weaponized, how what can be said in one language can’t always be communicated in or understood by another. In “Muslim Girl with White Guys, Ending at the Edge of a Ridge,” for example, Almontaser writes:

This “borrowed” language, however, doesn’t result in authentic connection—the (presumably) monolingual “white guys” merely “compliment my accent” and “make me write their names in Arabic / to show their tattoo artists later.” Language and speech render the diasporic subject always elsewhere, never at home. Trying to “find a certain feeling,” the speaker ends up talking only to herself: “Never,” the poem exclaims, “will they interpret me correctly.”

Interpretation and, more specifically, translation are at the center of Almontaser’s collection. The epigraph—“In the caverns of its death / my country neither dies nor recovers. It digs / in the muted graves, looking for its pure origin”—is taken from Abdullah Al-Baradouni’s “From Exile to Exile.” Almontaser includes two translations of Al-Baradouni’s work from the original Arabic amidst her own, highlighting both the influence of Al-Baradouni’s “syntax and music” on Almontaser’s lines and the paucity of Arab and Asian translation into English. Inspiration for this work, Almontaser notes, came after her discovery that “From Exile to Exile” was “the only poem of Abdullah Al-Baradouni’s that had been interpreted and made available”—despite his having been acclaimed by multiple sources as “Yemen’s most famous poet” upon his death in 1999.

Almontaser’s inclusion of Al-Baradouni’s work points to the constant presence of Yemen and the Yemeni people throughout the collection as a whole. “Why I Am Silent about the Lament,” the second of Almontaser’s translations of Al-Baradouni, is particularly evocative of her own negotiations between the visible suffering of contemporary Yemen and “what your TV doesn’t tell you” (“Guide to Gardening Your Roots”). “Poetry is only for life,” she translates from Al-Baradouni’s Arabic, “and I / felt like singing, not howling . . . Howling is only for widows and I am not / like a widow who wails on the silent casket.” Drawing the distinction between “singing” and “howling,” Al-Baradouni’s lines not only call attention to their own harmonies but also refuse an elegiac impulse. Likewise, in her “singing,” Almontaser similarly avoids the image of the mourning widow in order to figure Yemen—despite its immense and ongoing struggles—as anything but a “silent casket.”

Indeed, Yemen is portrayed as a lively place, pulsing with vibrance and contradiction throughout the collection—its landscapes red and gold and dry, its streets bustling and fragrant and treacherous—but perhaps no single poem captures these multitudes more powerfully than Almontaser’s “Guide to Gardening Your Roots.” Dedicated to the memory of Nawar al-Awlaki, the eight-year-old American girl of Yemeni descent killed in the 2017 U.S. raid on Yakla, the poem begins by invoking Yemen’s history of colonial trauma: “The British called us El Bab, the doorway. We are the entrance, our Red Sea the saltiest mother of waters. She is algae-thick, turning her copper as they die.” The lines quickly shift, however, to a celebration of حياة—life, with dignity and conviction, a faith in rebirth always located at the poetic center:

No healing exists beneath the ground. But haya grows in an empty desert. The implication being that water trickles back to its center. That even the unrooted can ascend.

In the poem Almontaser also analyzes American politics as well. “I tell myself, as an American,” Almontaser writes later on, that “I am not bound to just one land”—but as much as this stance allows her poems to wander from U.S. borders, it equally enables a unique perspective on their American roots as well. An important through-line of the collection is its careful rendering of post 9/11 New York City and, in particular, the ways in which the lives of its Arab American and Muslim American communities were irrevocably changed by their country’s own responses to those events. “Truth is,” Almontaser reveals in “Hunting Girliness,” “I quit being cautious in third grade / when the towers fell &, later, wore / the city’s hatred as hijab.” The impact of this hatred manifests in ways both predictable—airport suspicions, racist epithets—and minute: “it tells baristas / my name is tina,” for example. In “Feast, Beginning w/ a Kissed Blade,” danger and fear intrude on even the most celebratory of occasions when the sacrifice of an Eid lamb “in our Yonkers garage” result in a moment of legitimate panic: “Some [blood] leaks through the crack, / a jogger prepped to call the cops on his crazy neighbors.”

It’s Almontaser’s “Home Security After 9/11,” though, that levels the clearest indictment of the extent to which Muslim and Arab individuals, households, and communities were terrorized by their neighbors and fellow citizens in this aftermath—and no future anthology, course syllabus, or reading list that attempts to grapple with the realities and consequences of post 9/11 America will be complete without its inclusion. The title’s ironic play on “homeland security” is brought into immediate relief by the poem’s opening description of a targeted and unwarranted home invasion carried out by law enforcement: “At the break of moon, a front door Herculesed / to pine dust.” Moreover, Almontaser is clear that none of what she describes here or elsewhere—tapped phones, illegal police raids, violent threats—are isolated occurrences:

When the closing lines return to the title’s other inspiration—“My father gets a home security system—darklarge / pupils always watching. Just in case, he says.”—we feel the full weight of what has been lost, what has been taken from those whose lives fill the pages of The Wild Fox of Yemen: both home and security.

The price of diaspora is always a certain kind of exile, but The Wild Fox of Yemen espouses neither sentimental nostalgia nor doomed isolation. Carefully rendered and expertly voiced, it asserts both the contradictions and the inherent dignity of its chosen subjects with equal force and insistence. These poems overflow with an abundance of life—poignant and melancholic, sometimes tragic, sometimes hilarious, and always filled with beauty.