“These poems are extroverts”: An Interview with Emily Izsak

Emily Izsak is one of the sharpest young poets I’ve seen in some time. She is currently in her second year of U of Toronto’s MA in English and Creative Writing program. Her work has been published in Arc Poetry Magazine, The Puritan, House Organ, Cough, The Steel Chisel, The Doris, and The Hart House Review. In 2014 she was selected as PEN Canada’s New Voices Award nominee. Her chapbook, Stickup, is available on woodennickels.org and her first full-length collection, Whistle Stops, appears this month from Signature Editions.

Rob McLennan: I first became aware of your work through the occasional journal COUGH. Can you tell me a bit about the journal and how you first became involved with it?

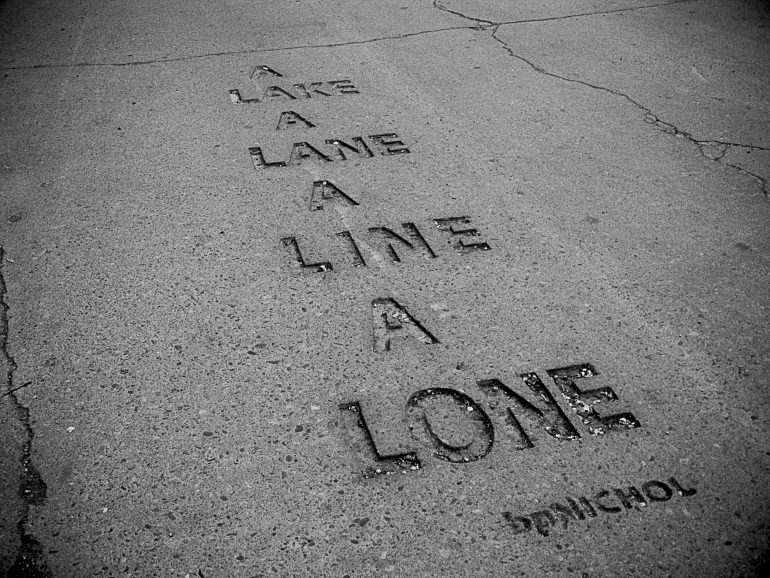

Emily Izsak: Cough is a magazine that the bpNichol Lane writers’ group puts out whenever we feel like it. It is edited by a different member of the group each turn. I edited the eighth issue and Brock Hessel edited the most recent ninth issue. Each issue features work from members in the group, but also work from other friends of the editor and friends of the group. Basically just writing that we like. We’re called the bpNichol Lane writers’ group because when there’s enough interest, we meet in or outside Coach House, which is on bpNichol Lane, to read and edit each other’s work. I became involved with the group through Michael Boughn. I took a couple of his classes at U of T. He mentioned the writing group during a summer course I was taking in 2014 and I thought that it sounded like a good time. I’m living in London (Ontario) now, and people aren’t so keen on trekking out to poetry meetings in the winter, but I’m hoping that the group will start up again when I’m back in Toronto in the summer. It is the best thing that has ever happened to my poetry and I feel very fortunate to have stumbled upon it.

RM: Who else is in the group?

EI: Victor Coleman, Michael Boughn, Oliver Cusimano, Brock Hessel, Adam Hendricks, David Peter Clark, Kelly Semkiw, Charlie Huisken, Michael Harman, Mitch Cram, Brad Shubat . . . but there are others who have been more involved in the past and new people who show up every so often.

RM: How do you feel the group has assisted your writing? Your recent piece on Mina Loy in many gendered mothers, for example, talks of being introduced to her work by Victor Coleman.

EI: Yes! Victor and Mike have introduced me to so many great books. They’re also really good at line edits and paying attention to sound, which is really important to me. I can now read over a poem I’ve written and anticipate the edits of specific group members (i.e. Victor would tell me to take out this “ing” because it sounds like the phone is ringinging. Pick up the damn phone. And Mike would tell me to switch “noun of noun” to “noun’s noun”). They understand my poetic goals and suggest edits accordingly. They’ll say something like, “this is an Emily line” or “It’s more Emily without the article.” We all have a similar aesthetic, but very different styles of writing, which is ideal. I never feel like I have to prove myself at our meetings. I have been in other workshops where I felt like I wanted to bring in my best work, work that I was already happy with, so that people would be impressed with me or so I could get a good grade. I know that I can bring an almost-good poem to Victor and Mike and the rest of the group, and nobody will think that I’m an almost-good poet, which is way more productive, because then we can work to turn that almost-good piece into a good one.

RM: Apart from Loy, what other poets have shifted the way you approach your work?

EI: The first part of Whistle Stops is a serial poem modeled after Jack Spicer’s serial poem form. I find it easier to write in short bursts than to write long poems. Reading Spicer showed me that I could keep writing these short poems, but string a bunch of them together into a cohesive, dynamic, and non-narrative whole.

Oliver Cusimano, who is part of the bpNichol Lane group, has invented his own form that involves using source texts systematically and raising letters in oddly shaped poems to spell out intersecting phrases. I try out an “Oliver poem” in Whistle Stops, but his work also showed me that there are tons of new and innovative ways to work with source texts. His invented form influenced a lot of my own experimentation with form and source texts in the second part of the book.

RM: Prior to Whistle Stops, you published a small chapbook, Stickups. What was the process of moving from individual poems to something chapbook-length, and eventually book-length? How did the chapbook first come about?

EI: In the third year of my undergrad, I took a Canadian poetry course with Lynn Crosbie. She mentioned to me that her friend, Stuart Ross, was looking for poetry manuscripts and asked if I had one. I didn’t have a manuscript, but I did have a bunch of individual poems. I never really thought about writing a book before then. I was writing poems and hoping that a magazine might publish one of them. I sent Stuart my makeshift manuscript, which was just those individual poems put into one Word document. He didn’t end up publishing it (for good reason, it was nowhere near ready), but I was able to clean it up and publish it with Shuffaloff/Eternal Network (Mike and Victor’s publishing imprint) a while later. Stickup was fun to make—one of my good friends, Ketzia Kobrah, designed the cover, and with the help of Google and YouTube tutorials, I taught myself how to use InDesign. I put the book together myself (with lots of input and design advice from Mike Boughn). After Stickup, I knew I wanted my next project to be a book that began as a book. Whistle Stops began as an idea for cohesion. I knew I was going to be on a train a lot because my boyfriend had just started medical school in London and I was taking courses in Toronto. I also had recently written an essay on Allen Ginsberg’s Iron Horse (another book that Victor pointed me to), so I was thinking about long train poems and the sexual content of that specific train poem. I also didn’t like coming up with titles for poems, and I liked the idea of just assigning a short poem to a train ride and titling it after the date and the time and the train number. I really like how ideas and themes and images started to develop in the book as I was writing it and how I could track patterns and either make a conscious effort to continue them or decide to squash them.

RM: You refer to Whistle Stops as your “next project” after Stickup. Did any poems from the chapbook make their way into the full-length manuscript?

EI: Nope. All new work in Whistle Stops.

RM: What was behind the decision? Was it project-based, or did you simply feel as though your work had moved on?

EI: Stickup is out in the world (and available as a pdf online), so I didn’t think there was any reason to re-publish those poems. Also, Jack Spicer had an orphic vision for serial poetry—move forward without looking back (however impossible that may be). The concept of seriality as Spicer conceived it serves a purpose in Whistle Stops—the idea of thinking back while moving forward on a train, arriving at stop after stop and not being in control of that forward motion. To go back to old poems would be counter to the momentum of the project.

RM: Given how you approached Whistle Stops as a serial poem in the Spicer mode, how has the experience changed the way you look at individual poems? I’m reminded of Michael Ondaatje paraphrasing Spicer in the first edition of The Long Poem Anthology, suggesting that “the poems can no better live by themselves than we can.” There is also bpNichol, who, when discussing his multiple-volume project, The Martyrology, offered that all the writing connects, even if only by virtue of being written by the same hand. What is your take on the individual poem? Can there be such a thing?

EI: Some of the poems in Whistle Stops have been published individually or in little groups in various journals. It did feel strange to see those individual poems out of the context of the whole manuscript—like seeing a short clip from the middle of a movie. Going along with Ondaatje’s analogy, I think these poems are extroverts. They can live by themselves for a bit if they need to, but they are energized by the company of others. The Martyrology makes a cameo in part two of Whistle Stops. Of course all writing connects. I think the main point of connection between the poems in Stickup is that they were written by the same hand. In Whistle Stops, there are more intricate points of connection as well as several explicit connections to poems written by different hands.

RM: Does this mean that you’ve moved entirely from composing poems to composing chapbook or book-length, self-contained projects? Beyond Whistle Stops, where do you see your work headed?

EI: At this point, yes. I’d still like to publish poems from new projects individually in journals and magazines, but I’m more interested in writing a set of poems conceived as a set than writing stand-alone pieces. After I finished writing Whistle Stops, I had a good few weeks of not writing and wondering if I could ever top this project and where the hell do I go from here. I spent that time watching a lot of YouTube videos, which lead me to clips of avian mating dances—which are crazy weird and silly, but also amazing that these birds didn’t watch their fathers do a silly mating dance but still innately know that they have to collect a bunch of blue shit to seduce a lady or head-butt her in the chest. Anyway, I’m writing a series of poems. Each poem is titled after a specific bird, and I’m thinking about how these mating dances connect to our modern human mating rituals as well as performance and theatre and voyeurism. Beyond that, I don’t know where my work is heading; hopefully somewhere interesting and still rooted in language and humor and sound.