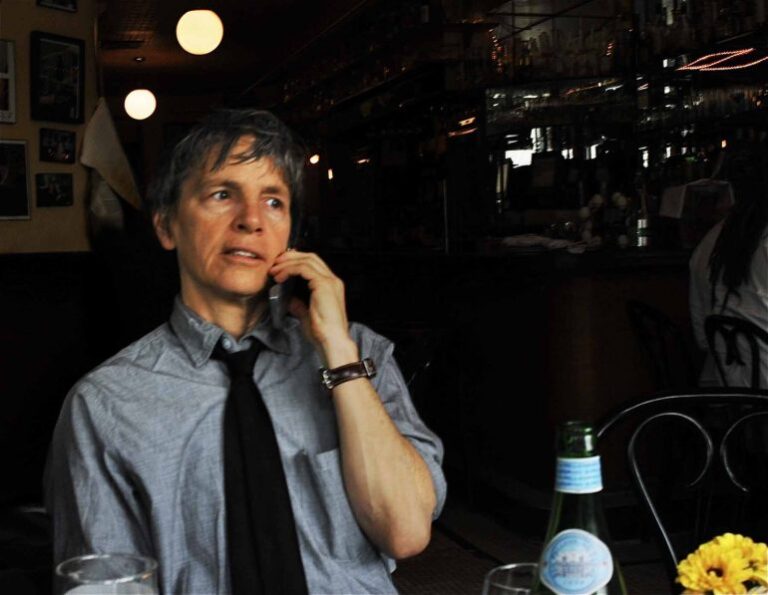

“These Poems Wanted to be Written Without Titles”: An Interview With Allison Benis White

Allison Benis White’s prose poems evoke a world of loss and wonder, in which the mysteries of our daily lives are illuminated as a story that finds its shape in the telling. She is the author of three books of poetry, Self-Portrait With Crayon, Small Porcelain Head, and, most recently, Please Bury Me in This. Allison has received honors and awards from the San Francisco Foundation, the Academy of American Poets, The Writer’s Center, and Poets & Writers magazine. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of California, Riverside.

Matthew Thorburn: Reading Please Bury Me in This, I was struck by how the book seems to advance along two different but closely related angles from its devastating dedication (“For the four women I knew who took their lives within a year”). I admire the delicate way in which the poem is written as a series of sentences that hover around and radiate out from the overwhelming, frankly unimaginable loss at the heart of the book. It feels at once like both an elegy for, and a conversation with, these four women. Would you talk about how you wrote the book?

Allison Benis White: This book began in a spiral notebook as a series of handwritten fragments and aimless paragraphs—I wrote in this notebook nightly for a long time, and once I started to identify a few sentences that interested and haunted me, I began to construct individual poems (that became a series of poems, or one book-length poem). It seemed clear from the beginning that these poems wanted to be written without titles, under the umbrella of one larger title (which eventually became “Please Bury Me in This”), and as double-spaced individual sentences strung together. So ultimately the writing process was really organic, and only as the poems materialized did I fully realize I was writing an elegy (although not a traditional elegy, but that is the closest word—you used the word “conversation,” which is close, too) for the four women lost to suicide, as well as for my father, who had recently died.

MT: Your poems most often (or always?) take the form of prose poems—and in this book you’ve really pared that down to the level of working with individual sentences that float in the white space of the page. What draws you to prose poems, versus poems broken into lines?

ABW: I was originally drawn to the prose poem in graduate school after reading Killarney Clary’s Who Whispered Near Me—I fell in love with that book, and became fascinated by the way Clary used prose poems to carve out a place for an unsentimental, wholly individual, intimate voice. At the time, I was writing lineated poems and was frustrated with some of the limits (I had created) within the genre. So I began to experiment with the prose poem initially as a way to break out of the rut I created, as a way to find a different texture and relationship with my voice on the page. Only recently have I begun experimenting with lineation again, and it’s been weird and exhilarating.

MT: What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

ABW: I’m working on a manuscript called “The Wendys” that currently has five sections, each devoted to a different Wendy (Wendy Torrance from Stephen King’s The Shining; Wendy O. Williams, lead singer of the Plasmatics; Wendy Coffield, the first located victim of the Green River killer in Kent, Washington; Wendy Darling; and contemporary photographer Wendy Given). The private, looming “Wendy” of the manuscript is my mother, Wendy (who disappeared when I was a baby and returned, suddenly, many years later—she actually changed her name from Trudy to Wendy as a child after reading Peter Pan).

MT: What have you read recently that moved you?

ABW: I think Peter Orner’s latest book, Am I Alone Here?: Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live is a work of genius—and it beautifully refuses genre categorization (although it was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism). As far as fiction goes, I’m in the middle of reading and loving Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow, and recently finished Han Kang’s stunning and strange novel, The Vegetarian. Also, in the last few months, I’ve deeply admired Ryan Murphy’s book of poetry, Millbrook, and Hadara Bar-Nadav’s collection, Fountain and Furnace.