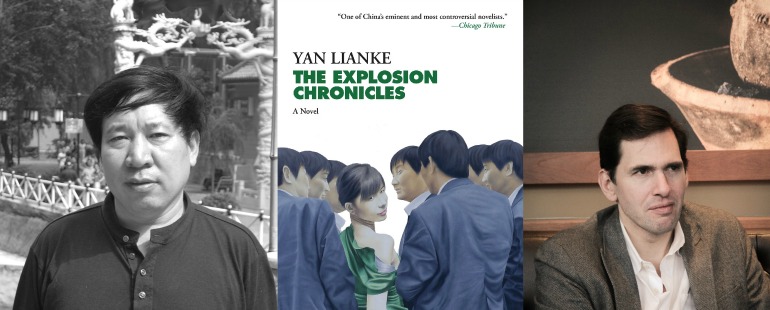

Translating China’s Modern History: An Interview with Carlos Rojas

The Explosion Chronicles by Yan Lianke is the historical account of Explosion, China, a fictional village so named because it was founded by people fleeing from an erupting volcano. It follows the growth of the town from a tiny community to a huge metropolis, focusing on the Kong family who are at the epicenter of the change. The book is part magical realism and part modern myth-making, with a healthy dose of social criticism peppered throughout, and is framed by a fictional Yan Lianke being commissioned to create this record of Explosion. In his translator’s note, Carlos Rojas says the book’s format is loosely inspired by the historical chronicles written by Sima Qian around 100 BCE.

Yan’s last novel, The Four Books, also translated by Rojas, was shortlisted for the 2016 Man Booker International Prize. His works have previously been banned by the Chinese government. The Explosion Chronicles was originally published in 2013, and the English translation is forthcoming in October from Grove Atlantic.

Besides his work with Yan and as a Chinese translator, Rojas is a Professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University. He’s written extensively about Chinese literature, and he co-edited The Oxford Handbook of Modern Chinese Literatures.

Graham Oliver: How well-known are the historical chronicles of Sima Qian that you discuss in the translator’s note as being the basis for the structure of this novel? Would most Chinese readers get the connection immediately?

Carlos Rojas: Sima Qian’s Records of the Historian is as well-known text in a Chinese context as something like The Odyssey is in a Western context. In addition, the work has been extremely influential in laying the foundation for an entire genre of Chinese historical chronicles—including both the official dynastic chronicles as well as more local chronicles. Chinese readers might not necessarily view Yan’s Explosion Chronicles in relationship to Sima Qian’s text itself, but they would certainly recognize that the novel is drawing on the tradition of historical chronicles that Sima Qian helped inspire.

GO: Having a fictional version of the author within the book as a framing mechanism is rare but happens in American literature. Would you say it’s more or less common in Chinese literature?

CR: This sort of framing mechanism is quite common in Chinese literature, and particularly in narrative fiction from the premodern period. For instance, the late-eighteenth century novel Dream of the Red Chamber (a.k.a. Story of the Stone), which is widely regarded as one of China’s most canonical literary works, opens with an elaborate series of metatextual frames, involving a sentient stone left over from when the goddess Nüwa repaired the heavens. Aeons later, the stone expresses a desire to visit the mortal world, and is reincarnated as a piece of jade that the novel’s protagonist wears around his neck. After the jade concludes its stint in the mortal world, it reverts to its original status as a sentient stone, but now with its surface inscribed with a textual account of its experiences in the mortal world—which is to say, it is inscribed with the text of the novel itself. This sort of elaborate framing device is somewhat less common in modern and contemporary Chinese literature, but it is not unheard of.

GO: Can you talk some about the dialogue in this book? There’s a lot of ellipses, repetition, and line breaks. Additionally, most of the dialogue is people asking one another for things. Does this add to the mythic property of the book, or would the same style not be out of place in a more realism-bound text?

CR: These are really interesting points, and I must admit I hadn’t really thought of the dialogue in this way. The punctuation represents my attempt to approximate the punctuation in the original (for instance, I often used ellipses in place of Yan’s dashes, because they seemed to work better in English). Now that you mention it, I suppose it is true that that a considerable amount of the dialogue involves people asking one another for things. But this also seems appropriate, given that one of the novel’s central concerns is the way in which contemporary China is driven by a metastasis of desire—an insatiable desire for limitless growth and profit.

GO: I’m sure this book will be compared to One Hundred Years of Solitude repeatedly. The author himself brings it up in the Author’s Note. However, can you speak some as to where this book and Yan’s work as a whole fits into contemporary Chinese literature? Are more writers engaging with the events in China over the past 50 years with this mix of satire, myth-telling, and magical realism?

CR: One Hundred Years of Solitude was indeed a very influential text in China, not only for Yan Lianke himself but also for an entire generation of authors who emerged in the 1980s and 1990s. Following the death of Mao Zedong and the official end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, restrictions on cultural production were loosened, and many Chinese authors began to experiment with different topics and modes of writing. Many authors during this period were directly influenced by magical realism, and some used a hybrid of realism and fantasy to explore the traumatic legacy of the Cultural Revolution. Where Explosion Chronicles is distinctive, however, lies in its melding of a variety of different literary modes—ranging from mythic and Biblical language, to historical and political discourses, to Yan’s distinctive blend of parody and pathos.

GO: Finally, give us some recommendations. What is being translated from Chinese languages that we should read, and what do you wish was getting translated but hasn’t yet?

CR: Well, I myself am about to start working on Yan Lianke’s most recent novel, The Day the Sun Died, which describes how one night virtually all of the residents of a remote town suddenly begin sleepwalking. The town quickly degenerates into violence, and hundreds of townspeople are killed. The novel just won Hong Kong’s Dream of the Red Chamber Prize, which is one of the prestigious prizes awarded for novels in Chinese. The novel has not been published in Mainland China, but the English translation will hopefully be out by the end of next year.

Another novel that I would recommend is Jia Pingwa’s Ruined City, a fascinating work that was hugely influential (and controversial) when it was first published in 1993, and which is now finally available in English translation by Howard Goldblatt. Jia Pingwa is arguably one of the least translated of contemporary China’s leading authors, but several of his other works are currently being translated into English, including my own rendition of his novel Lantern Bearer.

Beyond Mainland China, there is a really interesting body of literature by a group of ethnically Chinese authors from Malaysia, many of whom have relocated to Taiwan. Examples available in English translation include Li Yongping’s The Jiling Chronicles (Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin, translators), Zhang Guixing’s My South Seas Sleeping Beauty (Valerie Jaffee, trans.), and Ng Kim Chew’s short story collection Slow Boat to China (which I translated).