Translating Genderqueerness

Gender is, linguistically, often a tricky thing. As writer Erin Crouch points out, even in seemingly genderless languages like Estonian, a male bias can creep in. But, she notes, Estonian offers what natural gender and gendered languages can’t: the grammatical possibility of non-binary existence. Language creates and conditions identity; for instance, my non-binary identity is necessarily expressed differently in French and in English, if only because the genealogy of the singular “they” does not exist in French, where we’ve had to create pronouns that nonbinary people feel comfortable using. The most common form is “iel,” a compound of “il” (he) and “elle” (she); other forms include “ael” and “ol.” The toughest part of this work, however, is not the creation of new pronouns—it’s reconciling the whole grammatical system of agreements, where each and every noun, regardless of whether it refers to a living being or an inanimate object, is gendered according to a strict binary. In that system, where a neutral form does not even exist, how do you negotiate non-binary genders?

Turns out, there’s plenty of ways. Non-binary folks are a creative bunch, and we’re adept at creating new grammars. Genderqueerness is futuristic at its core, which is why you’ll come across so many genderqueer characters in speculative fiction—a genre where anything can literally happen, where any fantasy can unfurl. But translation does create friction in this process: gender identities meant to be ambiguous or kept secret until the reveal of an unexpected twist come up against not only other, more or less rigid, linguistic systems but also against the biases and preconceptions of translators. For example, in the French translation of Sam J. Miller’s dystopian novel Blackfish City, the translation of the pronoun “they,” used to refer to the character Soq, was flattened into “ils,” which is the masculine form of “they.” This would only make grammatical sense in French if Soq was literally multiple people: an invented pronoun would have been much less intrusive for the reading experience.

Genderqueerness is still relatively new, semantically and grammatically speaking, in French and plenty of other languages. All non-binary pronouns are fabricated, and outside of activist circles, people usually don’t know them or they deride them for being unnatural to the language. The academic response to them has been lukewarm at best. And using new non-binary pronouns in widely published books would put off mainstream readers, or so the logic goes. But if literature, speculative fiction in particular, is meant to confront us with other ways of thinking, why adhere to rigid forms? Why not experiment? There seems to be a reluctance, almost a fear, to engage so directly with the grammatical messiness of gender.

We can compare two cases of speculative fiction with non-binary characters translated into English: “Meteors” by Clara Ng, translated by Toni Pollard from Indonesian, and Customer by Lee Jong San, translated by Victoria Caudle from Korean. In both cases, the original language intentionally maintains a certain level of confusion regarding the gender of a character. In “Meteors,” Pollard explains, “the characters’ names were unidentifiable as either male or female, which exacerbated an issue that regularly arises when translating Indonesian—the lack of a gender-specific, third-person pronoun.” Though Ng did suggest using “they” to translate the Indonesian gender-neutral pronouns, Pollard ultimately rejected this because it could create “a strange impression of plurality” and decided instead to “assign a pronoun to each character, as had been my initial response in tackling the gender issue, and to leave the story’s surprise ending to deliver the author’s message.” Contrast this with Caudle’s approach to writing the character Ahn in Customer, who is described “as being a jungseongin (중성인) or ‘middle-gender-person’”—that is, “a blend of both genders.” Caudle decided to “use a modified form of the Xe/Xem pronoun set, Xe/Xyr/Xymself,” which allowed for a play on sex-determining chromosomes.

Caudle’s approach may seem bold, but it highlights the layers of the issue: “the themes of identity, androgyny, and pansexuality can only be further reinforced for the readers through careful curation of the description of nonbinary and gender fluid characters.” Pollard’s, on the other hand, approach unsurprisingly raised eyebrows. In a tweet, Jaymee Goh pointed out the main problem: “if your translation of a science fiction story with a gender fluid protagonist fails to reflect that fluidity and you *assign a gender* for your reader’s convenience, you have fucked up the speculative aspect.” Others were quick to remark that the translator’s strategy toned down the unfamiliar aspect of genderless pronouns for some readers but not all—what of genderfluid readers? What does it mean to consider “they” too outlandish, too unfamiliar? Clara Ng did give her approval for the final version, however, which calls for a more nuanced view of how both author and translator envision the representation and circulation of gender through languages—gender is personal, intimate, and social, collective, so decisions to translate non-binary genders may never be able to resonate with everyone.

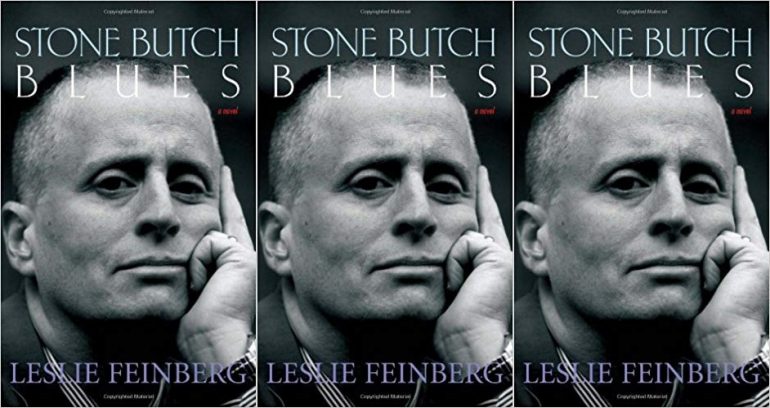

These questions aren’t restricted to speculative fiction: regardless of genre, the same problems of translation appear time and time again. Take, for example, the upcoming French translation of Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg. Noémie Grunenwald, the head of Hystériques & AssociéEs, the indie press that will publish the translation, is keenly aware of the text’s importance in the current French literary landscape, all the more so as it is the result of a collective translation process involving a dozen or so translators—something still rare or reserved for sprawling works like James Joyce’s Ulysses. When the project of publishing the translation of Stone Butch Blues was brought to her attention, Grunenwald had a very clear idea of the stakes: she wanted to make a classic of LGBT literature available to French-speaking audiences and to make Feinberg, who is mostly remembered for her transgender rights activism, also known for her communist politics. In parallel, the issue of the specific copyright agreement for Stone Butch Blues, according to which the novel could be translated but only under certain conditions, restricted publishing possibilities in France—hence why Grunenwald decided to create her own press, tailoring it to the project and relying on crowdfunding for financial support. Hystériques & AssociéEs was thus created, animated by a strong feminist ethos which required paying specific attention to the political intentions of the text, including what it says and does about gender.

One of the main issues that arose along the way was to harmonize the chapters translated by different translators; the intersections of gender and grammar obviously came up, since the way we use grammar to fashion our own understanding of who we are is a crucial element of the journey the text unravels. Evacuating the protagonist’s genderfluid identity under the guise of singular, uniformized gendered pronouns would have run counter to the very intention of the text. Instead, Grunenwald said that the translating team made the radical decision to alternate between gendered agreements (instead of using inclusive writing, which integrates both gendered endings into the same word and which would have broken up the reading experience too much), so as to materialize the journey through gender that the text conveys.

Caudle best expressed the stakes that underlie translating non-binary characters and genderqueerness: “As translators of queer literature, it is our responsibility to prevent queer erasure and to make a point of presenting bold, embodied queer translations which challenge readers and create a space for future queer translations to come through.” Translators need not sacrifice complexity, ambiguity, and fluidity, especially when it comes to gender: going beyond mere visibility, their task is to embolden and embody queerness, amplifying its futuristic potential and carving new paths through and between languages as they go.

This piece was originally published on August 1, 2019.