Travel, Tor House, and Negative Capability

Guest post by James Arthur

During the last few years I’ve been lucky enough to have some opportunities to travel, and not surprisingly, the places I’ve visited have begun showing up in my poems. In fact, these days when I sit down to write, I usually begin by flipping through my journals, which are full of notes like this one, made on a recent trip to Indonesia:

To reach the pinnacle of Mt. Bromo, we walk 3 km across “The Sea of Sands,” and then up the slope of the cone. Volcanic sand is blowing everywhere, stinging our eyes; we swallow it. The pattern of blown sand: streams of quickly moving particles being lifted into the air, and underneath, smaller grains rolling along the ground, like soldiers.

But as much as travel–no, let’s call it what it is: tourism–nourishes my writing, I think I’d bristle if anyone referred to me as a “travel poet.”

I suppose that a tourist is often thought of, unfavorably, as a dilettante who admires unfamiliar places and cultures mainly for their alienness, without trying to understand what it would mean to be a citizen of that unfamiliar place.

And I can understand the criticism. There’s a lack of rigor in the willingness to glide through the world, asking only to be dazzled, and no doubt it’s presumptuous to write about things you don’t really understand… but is it a poet’s job to understand? Doesn’t a poet need unknowingness to find that literary state of grace that Keats called “negative capability”: “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”?

I tell myself that I travel not for the sake of enlarging my understanding, but to encounter things that I can’t name, with the consciousness that my own country, seen through the eyes of an outsider, would be no less mysterious.

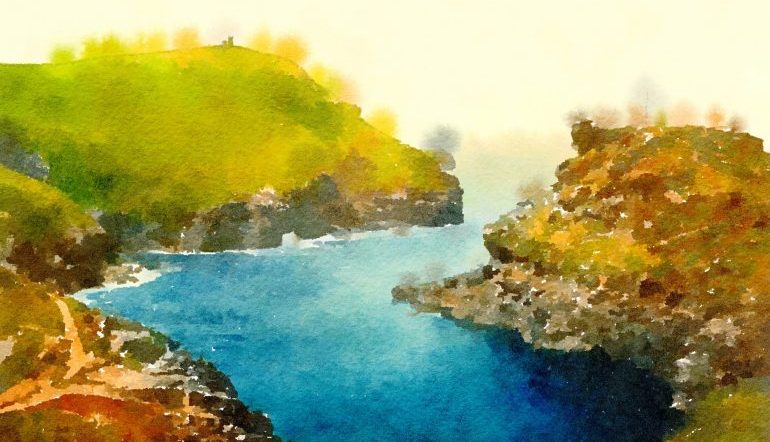

Some poets do find mystery at home. I think of the poet Robinson Jeffers, shown here, as a kind of anti-travel poet. Jeffers had an itinerant childhood, but from his early thirties onward lived in a stone house of his own construction in Carmel, California. Reading Jeffers’ poetry, you have the sense that it’s founded on a deep, ongoing investigation of that one patch of coastline where Jeffers planted his stake. Jeffers is supposed to have said, “There’s nothing like travel to narrow the mind.”

On February 19, 2006, I joined a small tour of Jeffers’ house, Tor House, and the adjacent observatory, Hawk Tower, both made of stones that Jeffers rolled or carried up from the beach. True to form, I dawdled at the tail end of the tour group, scribbling in my journal while the docent talked. Here are my notes:

In the bedroom where Jeffers died, the bed is still made; Jeffers wrote about this bed in “The Bed by the Window.”

John the docent kindly lets me sit at Jeffers’ desk (it has a wobbly leg) in the ground storey of Hawk Tower. On the roof of Hawk Tower, an inscription in Latin, reading, “I made Hawk Tower by hand, 1924.” I can almost imagine putting down roots, as Jeffers did, building a life out of stone, and living deeply inside one place. But am I equipped for it?

This is James’ fourth post for Get Behind the Plough.