Two New Books Show the Rapid Evolution of the Conversation Around Consent

There’s a long history in English-language literature of men pressuring women into sex. One example is John Donne’s 1633 poem “The Flea,” which begins:

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead.

The poem is usually interpreted as a witty bit of wordplay wrapped around a clever central conceit. The idea of wearing down a woman who dares “deniest” the narrator generally isn’t seen as a cause for concern; it’s all just a bit of fun.

Well, Donne was writing at a time when terms like “rape culture” and “enthusiastic consent” didn’t exist. This isn’t to say that the verbal pressure applied in “The Flea” is a form of sexual coercion, but it does reveal a very common attitude: as long as there’s no force, anything goes. Whether a person actually wants sex or not doesn’t matter, as long as they doesn’t actively resist.

An early sex guide reveals the persistence of this notion. The 1926 book Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique advises husbands that apprehensive wives must be “wooed into compliance.” Even today, mainstream sex guides barely touch on the subject of consent.

In some places, at least, we’re moving beyond this attitude. Two upcoming books reveal the evolution in notions of sexual consent, as well as how far we still have to go.

The first is the anthology Ask: Building Consent Culture, which will be published in October. These short essays strive to be both personal and educational. For instance, sex educators share acronyms for working toward fuller consent. One from the BDSM community is SSC, for safe, sane, and consensual. One from Planned Parenthood is FRIES (consent should be Freely given, Reversible, Informed, Enthusiastic, and Specific).

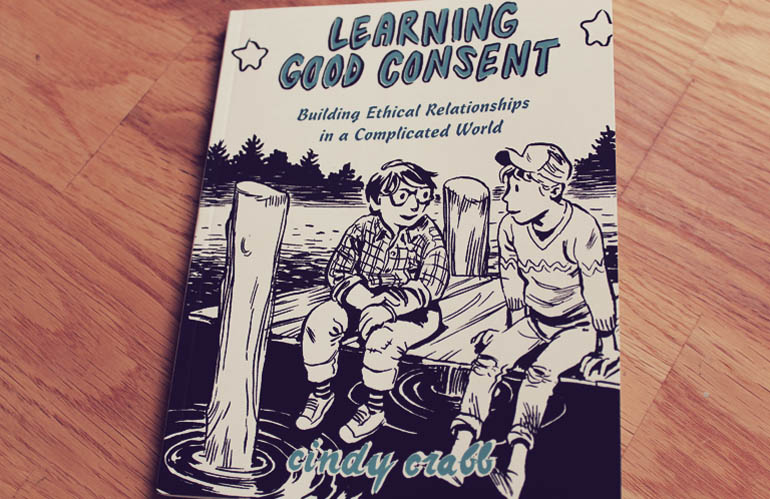

Learning Good Consent: Building Ethical Relationships in a Complicated World, which will be published in December, also has a practical bent, with sample questions to kickstart reflections and examples of workshop activities. Compared to Ask, there’s a more homespun feel to Learning Good Consent due to its hybrid book/zine form, with collage-style text, idiosyncratic illustrations, and occasional misspellings.

The contributors to both books attempt to be frank about how identity and privilege shape their experiences of sexual consent. For instance, Ask explores how having a mental illness can make it difficult to negotiate relationship boundaries, and the way working in the sex industry throws up its own set of expectations about sexual availability. One contributor writes about the uncomfortable duty of informing sexual partners about being trans, so that they can consent with full information.

There are authors here who represent these and many other perspectives. It’s heartening that the conversation around the subject is getting advanced (in certain circles) enough that we can appreciate the great diversity in how people express and experience consent. While both books are often polemical, and it’s clear that not all of the contributors are professional writers, it’s useful to gain a practical sense of what consent means for people from such different circumstances.

Overall, both books call for a shift away from the male-focused, heteronormative approach to sex (and sex writing) that has long been dominant. As one of the contributors to Learning Good Consent notes, “We were working off of this hetero script that says that guys are the drivers, they will go as far as they can with a girl and it’s the girls [sic] job to be the breaks, always guarding against men who will try to get as much as they can from her sexually unless we put a stop to it.”

It’s clear that at least within progressive, introspective communities, change through challenging this model has been rapid.