Umberto Eco and the Nature of Europe

The Italian intellectual and novelist Umberto Eco died on February 19, 2016, just four short months before the surprise result of the British referendum on the European Union. During his life, Eco, while recognizing the particular challenges faced by the project, was an advocate for a hopeful vision of what the European Union could be. His focus on shared history and shared culture as an immovable foundation on which cooperation can and should be built is a recurring theme in a number of his novels, not least his bestselling debut, The Name of the Rose (1980).

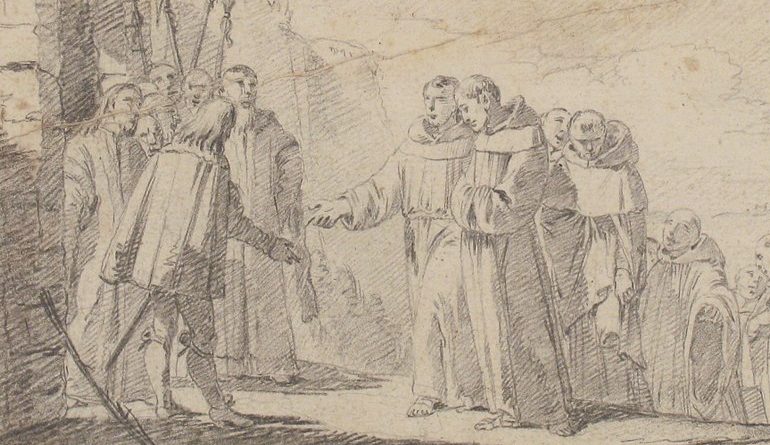

The isolated Benedictine monastery at the heart of this novel is a microcosm of Medieval Europe during the sixty-eight years of the Avignon papacy. During this time, division and discord between various monastic groups was fueled by an increasing challenge from a European populace facing general hardship following the Great Famine (1315-1322). It was a time when the establishment was facing challenges from within and from without, and when big questions were being asked, particularly around the role of wealth in the Catholic Church. While relishing the theological and philosophical arguments of the day as intellectually stimulating, the novel presents the suspicion, jealousy, and division created by a stolid rejection of other ways of thinking as a monstrous perversion of the diversity and the shared cultural heritage of Europe. In presenting and discussing these issues, The Name of the Rose speaks not only to the Medieval Europe of the novel’s setting, but also to our contemporary times.

The Name of the Rose cultivates a transhistoric aesthetic, both within its intertextual framework through anachronistic allusions to literary and historical figures such as Sherlock Holmes and Jorge Luis Borges, and through the narrative itself. Writing from the fourteenth century, some time after the events of the novel, our narrator, an aged Adso of Melk, states that “In the past men were handsome and great (now they are children and dwarves), but this is merely one of the many facts that demonstrate the disaster of an aging world.” This sense of a declining culture amid fears over the end of civilization is seen throughout the late Middle Ages as the scholars of the day compared themselves and their contemporaries unfavorably to scholars in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. From a contemporary vantage point, we may appreciate (or perhaps not!) that civilization did not end with the fall of Rome, and that the predicted decline of an “aging world” did not materialize. Indeed, the Renaissance was beginning even at the time of Adso’s writing, and the so-called “dark ages” themselves have been reclaimed by a number of modern historians, who have deemed their traditional characterization to be unfair and inaccurate.

Writing from a modern perspective, Eco identifies this notion of a declining civilization as a transhistoric moment. It is something we see again and again, most recently during the Victorian fin de siècle, and also in the postmodern age from which Eco himself writes. The message, then, is that the supposed end-times have been and gone and been again. This transhistoricism signals that one historical moment can be connected to another, or others, through an angled focus on past events, or to speak in more specific terms, that the Europe of the Middle Ages can reflect the Europe of our own times. In the tradition of all good historical fiction, the past is a mirror to the problems and preoccupations facing its contemporary audience, and in the case of The Name of the Rose, one of those problems is Europe.

The story of The Name of the Rose follows the Benedictine novice, Adso of Melk, as he travels with the learned Franciscan, William of Baskerville. Adso and William have a good relationship, though the values prized by their individual orders diverge on some fundamental issues, most particularly on the issue of monastic wealth. While the Benedictines believed that poverty had no place within a religious community and that common possessions were necessary, Franciscans believed that the Church and individuals within the Church should not possess material things. In addition to the particularities of these two distinct orders and their many factions, Eco’s novel includes or mentions a number of other monastic communities, from the Carthusians, who spent their days in isolation and silence and in some cases wore hair shirts as an act of penance, to the lesser-known Dulcinians, a heretical order to whom Eco attributes the rallying cry “Poentitentiam agite,” meaning “repent.” In the variety and in the disagreement represented between these different groups, brought together (or not, in the case of the Dulcinians) under the banner of the Catholic Church, Eco establishes for the reader a vision of Europe as a whole. The monastic communities are split along theological and philosophical rather than national lines, though there are a range of European countries represented in the nationalities of the various monks, from the English William of Baskerville to the German herbalist Severinus of Sankt Wendel, the Swedish Benne of Uppsala, and the Spanish Jorge of Borges. The polyglot nature of Europe reflected in this multilingual cast is central to the divisions and disagreements running in the background of The Name of the Rose, with the linguistic divisions serving to underpin the broader confrontations between the competing worldviews espoused by the different groups and individuals.

Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636), often referred to as the “schoolmaster” of Medieval Europe, famously noted that “races arose from different languages, not languages from different races,” with “races” here referring more to cultural than to physical traits. In other words, languages created differences from what was a shared foundation. Invoking the myth of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9), Isidore’s statement served to remind the denizens of Medieval Europe of the united humanity from which we fell, encouraging them to look beyond the arguably superficial differences of language. The challenge of seeing past these differences is presented in The Name of the Rose through the figure of Salvatore of Montferrat. Salvatore, we are told, speaks “all languages, and no language”; his extensive travels throughout Europe have corrupted his speech and made him difficult for the other monks to understand. This confusion of competing languages and the worldviews they represent produces an unpleasant, grotesque character when viewed through the lens of abjection:

His head was hairless, not shaved in penance but as the result of a past action of some viscid eczema; the brow was so low that if he had had hair on his head it would have mingled with his eyebrows (which were thick and shaggy): the eyes were round, with tiny mobile pupils, and whether the gaze was innocent or malign I could not tell: perhaps it was both, in different moods, in flashes. The nose could not be called a nose, for it was only a bone that began between the eyes […] The mouth, joined to the nose by a scar, was wide and ill made, stretching more to the right than the left, and between the upper lip, non-existent, and the lower, prominent and fleshy, there protruded, in an irregular pattern, black teeth sharp as a dog’s.

This patchwork of monstrous features presents a negative image of Europe as a deformity of warring cultures forced together. Beyond this portrayal, however, the text is sympathetic to the unjustly persecuted Salvatore. As with the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Salvatore is a product of his times and a creature of abjection. Salvatore’s final persecution leads Adso to comment that, “the sight of the wretch . . . moved me to pity. Salvatore’s face, as I have said, was horrible normally, but that morning it was more bestial than ever.” That Salvatore appears more grotesque as he comes under increasing persecution connects his deformity to the way he is viewed, rather than to any inherent characteristic of Salvatore himself. Ugliness, like beauty, then, is in the eye of the beholder.

Julia Kristeva defines the abject as “something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object.” The struggle for linguistic and cultural supremacy being fought in the backdrop of the monastery in The Name of the Rose would seek to dismiss or otherwise revile the cultural and linguistic diversity of Europe, but this diversity is, as Kristeva states, that “from which one does not part.” However much the monks wish to be rid of Salvatore, however much he is cast out as abject for his embodiment of cultural and linguistic diversity, he is inescapably a part of the European Catholic community at this time, and is in many ways an embodiment of it. Through the narrative sympathy for Salvatore, Eco’s novel ultimately promotes the variety of European culture and language, and castigates the rejection of that which is different, which so corrupts the multicultural ideal.

The various theological disagreements which unfold in Eco’s medieval monastery and the historical context in which they are set in many ways echo the discussion and debate that surrounded the growth and expansion of the European Union, or the European Economic Community (EEC) as it existed at the time of Eco’s writing—particularly, it must be said, following the UK’s admission into the Community in 1973—and to the ongoing issues facing Europe today. While Eco could not have predicted Brexit, his response to it would have been clear: just as the monks in The Name of the Rose cannot reject Salvatore, Britain cannot truly reject Europe. Culturally and historically, the United Kingdom is European, and in spite of Brexit, and whatever the eventual outcome, so it will remain.