“Unassimilation” and Nabarun Bhattacharya’s Harbart

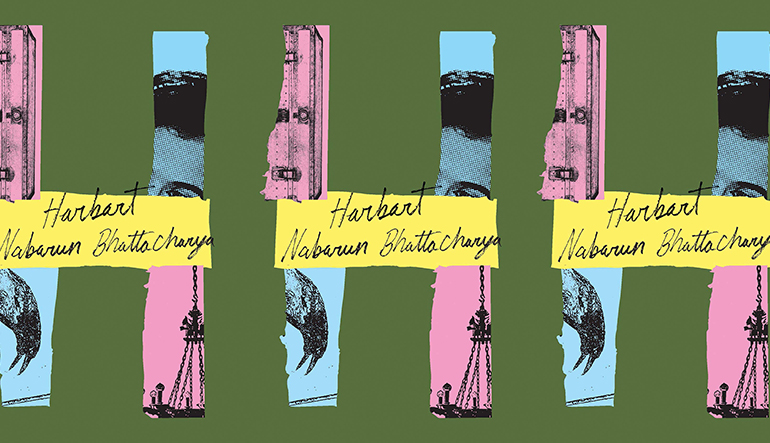

Sunandini Banerjee’s freshly released translation of Nabarun Bhattacharya’s cult-favorite Harbart, the first English version to make it to the United States (the book was originally written in Bengali in 1993 and has been translated into English multiple times in India), presents a nuanced portrait of Calcutta that reinvigorates the spirit of revolution in a time of clashing social and economic values. The abject Harbart, orphaned at a young age and raised in his uncle’s hostile house, finds himself seemingly endowed with the ability to converse with the dead and opens a business based on his supernatural talent. Bhattacharya’s swift pace and biting satire spin Harbart’s trajectory into a tale about much more, encapsulating the impotence of the machinery of the state, the oddities in the coexistence of greedy capitalism and old tradition, the non-finality of death, and more in just 101 pages. With the release of Banerjee’s translation, Harbart is now available to an international English audience, delivering to these readers a compelling, energetic portrayal of a life rooted in paradox.

Set roughly in the late 1960s through the 1980s, Harbart depicts the astonishing social disparities in Calcutta brought about by the quick growth of globalization and neoliberalism. A small few jumped, in this time period, into a neoliberal lifestyle, heading to wild financial gain, while a vast majority of others were left to poverty and working class drudgery. In 1967, West Bengali police shot and killed around eleven villagers who insisted on their right to some crops, and the villagers responded with an armed revolt, leading to the formation of the Naxalite party, whose ideology is founded on that of Mao Zedong. It became strongest in Calcutta in the early ’70s, where many radical students joined the movement, following its call to assassinate “class enemies,” or those businessmen, politicians, landlords, etc., who withhold power from the people. In response, the Indian Army and police launched a brutal counter-operation, killing hundreds and imprisoning and torturing over twenty-thousand others. To this day, continued violence associated with the Naxalite movement is said to have killed over twelve-thousand civilians and displaced more than twelve-million.

The celebrated radical writer Bhattacharya (1948-2014) sets Harbart in the midst of this tumultuous moment in contemporary history. It might be easy for an international reader to miss the exact political implications that Bhattacharya wrote, as his deft storytelling relies heavily on the intricacies of language and the responsibility of the reader to have or seek out contextual knowledge. An immense fortune, however, lies in the carefully tailored glossary of translated terms, specific political events, and cultural knowledge for those moments where valuable information hides camouflaged behind Bhattacharya’s incredibly sharp wit. In Banerjee’s translation, Harbart refuses categorization—its characters swing between the poles of capitalism and tradition, the afterlife finds its way into lived reality, revolution breathes beneath the silencing state—challenging our notions of stability on both social and logical planes.

Harbart follows the titular Harbart Sarkar, a young orphan who lives in his uncle’s house. He is scorned by everyone in his family, except his great aunt and one of his nephews, Binu, a Naxalite who is shot and killed by the police while painting Mao Zedong’s likeness on a wall in 1971. The novel begins with Harbart’s suicide after his business is exposed as a lie, and then jumps back and forth in time to recount spurts of his life. After Binu’s death, Harbart moves into his old room where he discovers human bones kept in a trunk. Horrified yet intrigued, he begins storing his own possessions in the same trunk, piquing his interest in the afterlife. As Harbart grows older, he becomes increasingly focused on the occult, obsessing over a few books on the subject, from which excerpts pepper the pages. Harbart’s early life does not amount to much—his time is mainly spent escaping the bullying of his nephews—but fifteen years after Binu’s death, he has a dream in which he hears Binu telling him where he hid his diary before he died. The location turns out to be correct. Harbart, however, forgets that Binu had actually divulged that information to him moments before dying fifteen years earlier; instead, he takes the dream to mean that he now has a supernatural power. He starts a business, “Conversations with the Dead. Prop: Harbart Sarkar,” conducted out of the small bedroom that once belonged to Binu, and his reputation turns quickly from abject to revered.

Harbart’s business epitomizes Bhattacharya’s representation of living in a society entwined in both modern globalization and ancient tradition, left in the lurch of neoliberalism. His techniques for communicating with the dead are neither exactly western nor eastern, but are rather a motley “hodgepodge.” Bhattacharya writes, “Richet, Crookes, Conan Doyle, Meyers—there should be no attempt to connect Harbart to this glorious tradition. He had no relation either with those in Calcutta who devoted themselves to the study of souls and free spirits, among whose number could be counted a living legend of the cultural world. Harbart was a freak”—a freak who lived in the middle of two sides, neither firmly capitalist nor firmly devoted to tradition. Community members and prominent figures travel to Harbart’s bedroom to ask how to resolve issues created by their loved ones’ deaths, and Harbart keeps his business afloat by providing mysterious messages or instructions for what they can do to appease the souls of the dead. As his business grows in fame, a man who specializes in profiting off of whatever fake product he can turn into a global sensation, Surapati Marik, visits him with a proposal to turn his company into an international capitalist venture. His pitch to Harbart consists almost entirely of stated visual markers of wealth and western corporate prestige:

A gleaming glass office . . . AC-cool and classy. Pictures on the walls. A girl at a computer. The shelves shining with rows of pricey books on the subject. Music playing, softly-softly. Dim lights. Carpets. Five hundred rupees a visit. Minimum. Much more for special cases. Then Bombay, then Delhi. . . . Alongside, detachment, indifference. Then Dubai. Bahrain. Dead sheikhs, live sheikhs. Air India. Tata Sierra. RSVP. . . .

Harbart agrees to work with him, moving a business inherently centered on an older cultural acceptance of the occult toward a globalized, entrepreneurial money-making scheme. Harbart’s suicide occurs, however, before any of Marik’s plans begin, leaving his shift to western consumer expansion in the same mixed composition as Harbart’s necromantic techniques: merely the ghost of potential. Harbart, and Calcutta by extension, is neither entirely capitalist-centric nor tradition-purist, instead inhabiting a middle ground comprised of slivers of each.

Though Harbart’s solutions for his clients are either fabricated or based in his knowledge of the community rather than necromancy, Bhattacharya makes a compelling tale out of the unfinished business of Harbart’s nephew, Binu the Naxalite. Binu and his friends had been stuffing sticks of dynamite into the mattress in his room—which becomes Harbart’s after Binu dies—intended for an assassination, but Binu was shot before they carried out their plan. After Harbart’s business is exposed as a sham by the West Bengal Rationalist Association and he dies by suicide, his family decides to cremate his mattress along with his body. He spent so much time in the room, it had become a part of his identity. Unknown to all in attendance at the cremation, they sent a mattress chock-full of dynamite straight into a fire, exploding in a revival of revolutionary spirit from twenty years earlier. Bhattacharya’s ingenious inclusion of Binu’s dynamite in Harbart’s cremation scene points the reader to what may be the thesis of his novel: that human life eternally resists the order by which the those in power attempt to impose rule.

After the explosion in the crematorium, the characters in the novel are unable to come to any solid conclusions about why Harbart would have intended to blow up the crematorium. Only the readers are privy to the true reason—Binu’s crushed participation in the Naxalite movement—and Bhattacharya uses this dramatic irony to emphasize the impotence of state surveillance and control: “The deplorable series of events that unfolded around the cremation of Harbart’s bloodless body inescapably signal that when and how an explosion will occur, and who will cause that explosion—of all such knowledge the state machinery remains woefully ignorant still.” Although the state police killed Binu and many other young Naxalites, and effectively crushed a revolt, through Harbart, an ineffectual, false conduit between the living and the dead, their revolutionary spirit and sparks return from the afterlife to live on.

Bhattacharya’s biting content challenges the reader in multiple ways, presenting the unstable—whether it be structure, time, or value—as a form of stability in itself. Harbart begins with its main character’s death, and promptly jumbles time throughout the novel to give a sporadic, nearly dreamlike account of Harbart’s life. The slim book covers decades and beyond, while the mosaic-like storytelling disorients the reader in a reflection of the mess left behind by globalization, the pockets of society its glimmer overlooks. To borrow Siddhartha Deb’s term in the novel’s afterword, Harbart and Bhattacharya’s work itself remain staunchly “unassimilated,” and it is in this unassimilation that their magic truly lies: there is an abundance of life between our expectations, rooted firmly in what is often cast aside, what doesn’t fit neatly in our predetermined lines. Writing within the form of the novel yet against its western traditions, Bhattacharya’s presence in the international English literary sphere beckons the reader to look closer into the chaos.