Uncanny Masculinities

If someone were asked to discuss contemporary British masculinity, it is unlikely that they would begin with superstition and folklore, yet that is precisely the framing this topic receives in two novels by British authors, Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss and The Devil’s Footprints by John Burnside.

Moss’s novel relates the experiences of a small family—a husband, wife, and their teenage daughter—as they immerse themselves in the day to day life of the iron age alongside a group of students and their professor at a specially built site in England. The father is an amateur iron age obsessive with a grievance against the formally educated. His sense of inferiority and relative powerlessness (which is sympathetically portrayed) fuels his mistreatment of his family, particularly his daughter, over whom he exerts a menacing control. His sexism and racism are tied to his interest in the iron age past, which he views as a golden era defined by true native Englishness and properly allocated gender roles.

We are unsettled by the father’s fascination with bog bodies, people “who could now exist only as victims, as the objects of violence,” as it speaks to something innately dangerous in his particular form of masculine self-expression. His is a masculinity that is affirmed through violence and control. But it is important to remember that it is not only the father who is culpable in the end. What, for him, lies close to the surface, is also present within other characters—those who benefit from the patriarchy, like the university professor and his male students—who share in or enable the dark turn of the narrative’s dénouement.

Over the course of the novel, Moss weaves old iron age beliefs, rituals and superstitions into the fabric of the text, blending them seamlessly with modern behaviors and attitudes: “[T]hat was the whole point of the re-enactment, that we ourselves became the ghosts, learning to walk the land as they walked it two thousand years ago, to tend our fire as they tended theirs and hope that some of their thoughts, their way of understanding the world, would follow the dance of muscle and bone.” The chilling crescendo of the novel only works because of the historic resonances of patriarchy across time, even times as far distant as the iron age and the present day. The dark side of modern patriarchy and of modern masculinity, Moss’s text suggests, has much in common with the barbarism of ritual violence in Britain’s iron age past. To dig up the past in this context is also to dig up the dangerous impulses simmering beneath the surface of contemporary civilization. Only the characters who reject the systems and structures of modern patriarchy (both the men and women) are able to resist the hypnotic pull of the final ritual.

Burnside’s novel creates similar resonances, though in The Devil’s Footprints, the links are drawn between the local folklore of a fictitious town on the east coast of Scotland and a more personalized expression of dangerous masculinity. Burnside’s novel is narrated from the perspective of a man looking back on his life from a point of crisis in the present. He relates his own dark thoughts and wrongdoings, constantly questioning his own motives, which remain ambiguous. Did he, as a child, knowingly leave his tormentor to die after pushing him into a pit of water, or did he trust the boy would be found? Is he attracted to underage girls, or does he believe the schoolgirl, Hazel, he (chastely) shares hotel rooms with is his daughter?

Burnside’s narrator is tormented. Not only by these questions about his relative guilt or innocence, but by an unseen force, a hallucination, a presence that reaches out from his dreams into his waking moments. Is he insane? He claims to himself that his road trip with Hazel was carried out under the cloud of some temporary insanity, but the reader cannot be sure. These questions surrounding the truth of the narrator’s character and his experience hang like a fog over a novel that plays around the edges of the gothic and supernatural.

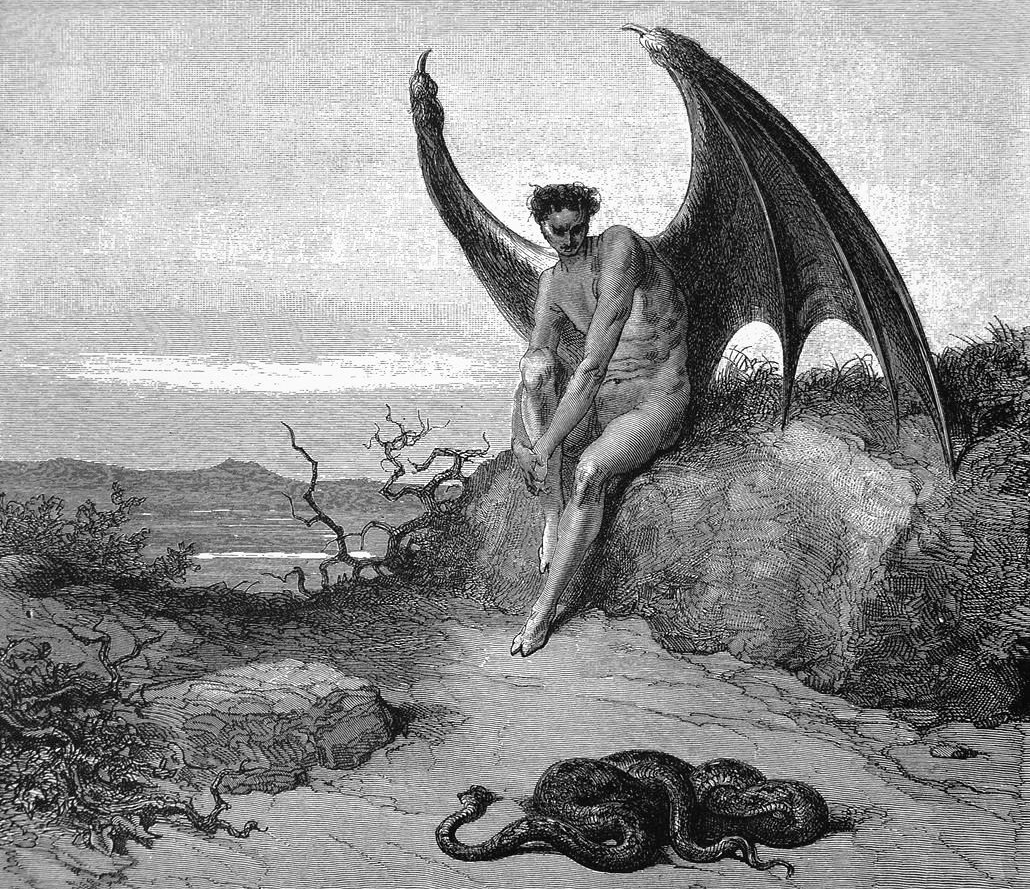

It is said, the narrator tells us, that one morning, the inhabitants of Coldhaven woke to find, running through their snow-covered village, “neat, inky marks laid down by some cloven-footed thing,” a phenomenon they called “the De’il’s Footprints.” It is implied that perhaps the devil did indeed visit Coldhaven, and is even there still, in the dark urges of the protagonist, and the various evils and tragedies of the town.

Burnside’s devil is a distinctly male presence, associated, at various points, with different men in the text. One of the opening scenarios of the novel involves the narrator’s old high-school girlfriend, Moira, now a grown woman, and married with three children. When Moira drugs her two sons and sets fire to them and to herself inside her car, she does so under the belief that her husband is the devil and that her sons, as a result, are also tainted. She abandons her daughter, Hazel, on a roadside before the fatal act. Is Moira mad? Or is she, like the generations of women in the old fishing community before her, a woman “whose gaze did not stop at the horizon, but travelled out into the beyond”?

The narrator seems to answer that question at the end of the novel: “Sometimes I see Tom Birnie out in the early morning cold, his face haggard from illness and dismay. It turns out he wasn’t the devil after all; he was just a man.” In this, the narrator is answering as much for himself as for Moira’s husband/Hazel’s father, Tom. He isn’t evil or possessed; he is merely as capable of good or of evil as the next man. Like the men in Moss’s novel, Burnside’s protagonist has a dark side, one that he feels pulling at his thoughts and actions at various points in his life. Ultimately, however, it is human nature rather than the supernatural that decides how far into darkness these individuals will tread.

In both novels, contemporary masculinity is tied to dark impulses, which find their echoes in supernatural beliefs and traditions. In Ghost Wall, Moss shows how contemporary patriarchal embeddedness provides a path towards the violent iterations of these same structures inherent in historic ritual, while Burnside, in The Devil’s Footprints, explores the idea of the supernatural as an externalization of internal struggles. For both writers, the historical/supernatural elements are presented as a form of cover for enacting or contemplating forbidden desires at the root of their troubled male characters. As Burnside writes: “There must have been times, in the life of every one of those upright men and true, when he imagined letting go of everything that kept him steady and allowing himself to slip into the incandescent calm of the truly possessed.”