Violets’s Mothers

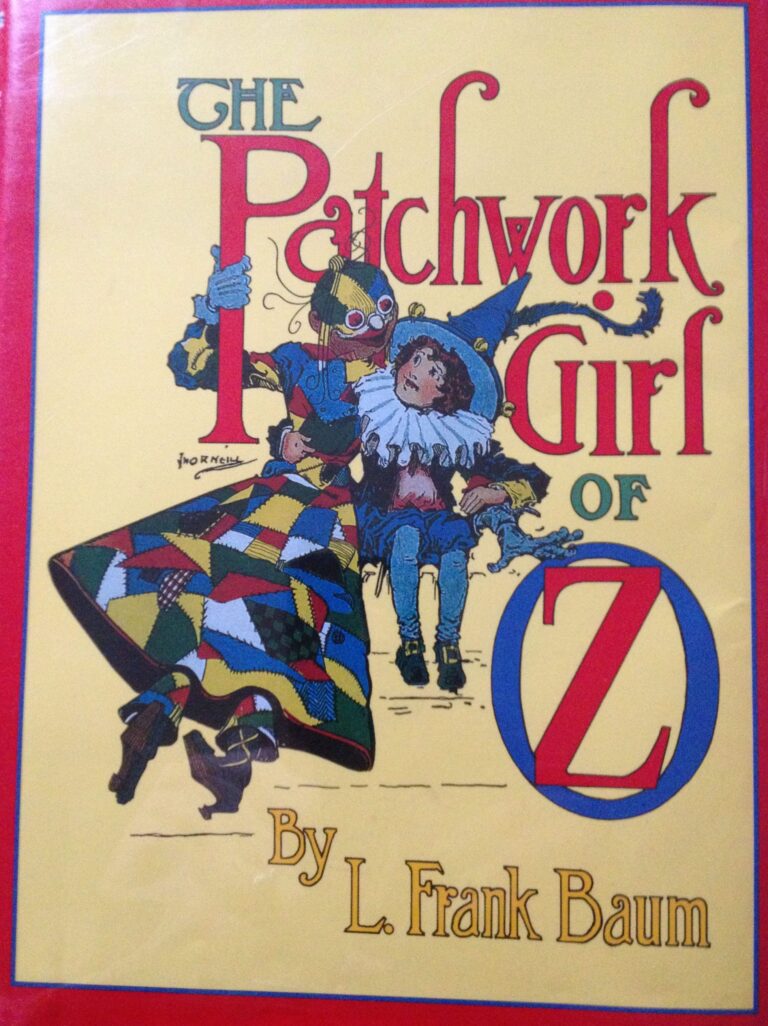

Violets, Alex Hyde’s debut novel out earlier this year, follows two British women over the span of less than a year at the tail end of World War II. The chapters flip back and forth between them as the book moves forward in time. What complicates this structure is that the two women share the same name—Violet, hence the title—and it is occasionally difficult to know which Violet we are following. This is clearly an intentional choice, as while Hyde is interested in exploring the women’s differences, her real focus is on what they have in common. In order to do that, she creates a separate narrative voice that allows us access to the most important thing they share. At the start, we cannot imagine how these two women’s stories are connected, but by the end, we understand that what they share is far more important than what keeps them apart.

The novel begins, abruptly, with a bucket of blood:

There was the enamel pail of blood. She couldn’t think what she had done with it. She hated the thought of someone else emptying it.

Was that what it meant, lifeblood? Placental, uterine. She had seen the blood drop out of her into the pail. It came with the force of an ending.

And the pain. Her lower right side. The gush of the blood. Thinnish, not thick. Not like anything carrying life.

Right from the opening, the novel focuses on the body, and the intricate connections between the body and life and death. The prose is short and staccato and forceful. There is little in the way of introduction; the reader is dropped right into the story. Hyde’s stylistic choices—the use of short paragraphs and chapters, a good deal of white space, and no quotation marks accompanying the dialogue—mean that the book moves extremely quickly. Although the time period is historical, the prose and the focus on the body make the book feel contemporary, making us understand the timelessness of many of the events of the book.

We quickly learn that this passage’s “she” is Violet (for the purpose of this essay, we will call her “Violet 1”), that she has just miscarried, and that she’s in the hospital with her husband, Fred. After the doctor tells her that the baby is gone and that there is not a reason to hope that she can get pregnant in the future, there is a strange passage, in italics, that is difficult to decipher:

See?

See her, there?

Yes, you.

Pram Boy, pill-boy, you know who.

No flood for you,

no gush or release

of blood into the water,

filaments and threads,

For it is you who will be carried

while the others are shed

(I’ll take the one with the curls, your mother said.)

It is a poetic voice, with occasional rhyme and occasional humor. The narrator speaks in the present tense, from some moment in the future, and it is an insistent voice, one that seems to demand to be listened to. It’s a direct address, as well, although at this point in the narrative we don’t quite know who is being addressed or who is speaking. This voice, though, feels like the spine of the narrative, and it will become a voice that speaks throughout the whole book, a narrator that unites the two women.

In the following chapter, we meet the second Violet (“Violet 2”). It begins as follows:

No. Still nothing.

Violet pulled up her knickers and swilled out the pan.

Every time she would check. Every slight feeling of wet. She would go to the lavatory or somewhere she could pull up her skirt, hoping for a bleed. But no, there was only the pale slick smeared on her inner thighs, the glistening string like egg white.

At first, of course, we think this is Violet 1, but then we wonder, as this Violet is clearly hoping not to be pregnant, and this doesn’t fit with what we know about Violet 1. Slowly, we begin to understand that this is, indeed, a different woman. This is Violet 2. Two Violets, wanting the opposite thing. The body, though, is at the center of their desires. The two openings are mirrored, as the two women are presented in a similar fashion, but with different results.

In this chapter, we hear again from the italicized voice:

Oh ho, Boyo!

But you are there,

pretty as a picture, coming down the stairs

Caught on a moon-edge, you came with the tide,

A boy all coy and evolving,

known only by what you are not.Son of a bloodflow, stopped.

It seems clear, now, that the narrator is addressing the to-be-born child. By inserting this voice in both of the women’s chapters, we now begin to understand that, somehow, the trajectories of these two women are heading toward each other, with the baby at the center, although we don’t yet understand how they will intersect. As the novel progresses, we hear from the narrator quite frequently, but almost always with Violet 2, rather than with Violet 1. This makes sense, of course, because the to-be-born child is with Violet 2. Violet 1 is trying to get on with her life; she is trying to imagine her life without a child.

And so, the two storylines move forward in time, the chapters alternating between Violet 1 and Violet 2. As their individual stories unfold, it becomes easier to track which character is which, although it is clear that Hyde wants us to also be considering the ways in which they are similar. Fred returns to the war, leaving Violet 1 with her mother, sister, and friends. Violet 2 leaves Wales, and she, too, goes to war, serving in Naples, keeping the pregnancy a secret. The women’s worlds become populated: Violet 1 sees her sister marry an American soldier and leave for the States; Violet 2 becomes enamored of a fellow ATS worker named Maggie. They both work and play; they both celebrate VE Day. Both women are living busy lives and yet both are lonely; their bodies have betrayed them in opposite ways.

In time, of course, Violet 2’s pregnancy can no longer be kept secret, and she is put into a medical facility in Naples with other pregnant women. We do not see the birth through Violet 2’s eyes; instead, there is a chapter narrated by the voice that details the birth:

Turn then, Pram Boy

Turn your sweet head.

As the afternoon falls quiet

in the dry September breeze;

rustling,

leaves.Turn,

swim down,

take your last amniotic sips.

The chapter ends after the birth, with the baby looking into Violet 2’s eyes. It is a truly extraordinary chapter. By using the direct address, which almost always provides an intimate connection between the narrator and the person to whom the narrator is speaking, the unnamed narrator allows the reader to be with the baby at the time of birth.

Shortly after this, Fred is due to return home from Burma. Violet 1 waits and waits; she goes to the train station day after day. She is nervous, worried that she won’t know what to talk with him about, worried about what their life will look like without the ability to have children. On the day Fred returns, the narrator returns to Violet’s section as well, to allow the viewer to see their reunion from the outside: “So tap the window with your tiny claw, peer in / Later, when they are grasping at the evening’s ends / See how they linger in each room of the house.” As with the birth, this voice allows a unique point-of-view; it allows the reader access to the most private moments of life.

Fred tells Violet 1 that he would like to adopt a child, and they begin the process. Violet 2 has returned back to England with her baby, and she is living near a convent, where her baby is in a nursery, waiting to be adopted. As the novel speeds toward its end, the chapters get shorter and shorter as the distance between the two women shrinks. We know where we are headed. Interestingly, the confusion between the Violets reappears at this point: as they become physically and narratively closer, the differences between them begin to disappear.

Violet 1 and Fred go to the nursery to see the available babies. They walk through a quiet room, the babies napping in cribs. Violet is not feeling much of anything. But then:

As she turned, she saw, almost behind the door, an old pram. The hood was missing and the handle was crooked.

It was huge and deep like a boat. A child stood wobbling in it.

The nun nodded, gestured for her to proceed.

Violet smiled. The child mouthed sounds and squealed.

Violet is relieved, and so is the reader. The narrator, who all along has been referring to “Pram Boy,” finally makes sense. We know this is Violet 2’s baby, and we know this is the right baby for Violet 1.

The final two chapters are written solely in the narrator’s voice. The second-to-last chapter is about the relationship between Violet 2 and the baby. It moves in time from the nursery to the baby’s adulthood and back again to the nursery. It traces the man’s search for his birthmother, recounts the day they re-met, and presents the arc of their life together. It is sad and lovely and full of heart. At its conclusion, the chapter returns to the nursery and what Violet 2 said to the baby on the day he left with Violet 1, a premonition that came true:

I

will

see

you

againmy

son.

In the final chapter, the narrator recounts how the child and Violet 1 had shared information over the course of their lives about the adoption. Violet 1 is dead at the time of the telling, and the narrator asks one final question:

But Pram Boy, do you know why, when your mother died, she waited until you left her hospital bed?

No goodbye, that way, not again.

For your mothers did not leave you; you were kept.

In the end, we see that Violets is not only about the two mothers, but it is a love story for the child as well. The narrator is speaking directly to the child, telling him the tale of his adoption so he will understand that he was doubly loved. Both women loved the child: while one gave birth to him, the other brought him up. This narrator is able to move through time, to show us what happens beyond the present moment of the novel, to give us a sense of the rich life that was lived after the child was handed from one woman to the other. By using this unique exterior voice—which by the end we understand to be the true narrator of the book—Hyde gives the reader access to this most intimate and complicated relationship, between a birthmother, an adoptive mother, and the child at the center of it all.