When a Workshop Goes Bad (Part 2)

Last week, I wrote about some bad experiences that I’ve had in writer’s workshops. Some of my past workshops fell apart because of:

- Tit-for-tat commenting: Writers exchanging immature cheap shots with each other.

- Generic commenting: Lazy comments that don’t help anyone in particular.

- Focusing on political issues: Arguments that have nothing to do with the story.

- Consensus-seeking: Workshoppers trying to create a dominant view about a story.

- My-story-has-to-be-the-best-attitude: Egos getting in the way of honest commenting.

What do you do when your workshop is suffering from one or more of the above symptoms? I suggest trying to salvage the workshop by collaborating with the more reasonable members to create a more constructive environment. It takes time and energy to organize a workshop, so the members should not abandon it if it begins to veer off in the wrong direction.

Years ago, I was in a workshop that wasn’t working because some of the members were being rather immature and selfish (see Problems #1, #2 and #5 above). One of the members decided to take the initiative to get the workshop back on the right track by establishing a set of ground rules that dictated how the members should behave. These rules were agreed upon by all of the members, and made a huge difference in making the workshop click again.

In this particular group, the members had to be reminded about the very basics of civility, so our first rule was “Be polite and courteous.” In other words, no shouting and/or childish name-calling. We banned comments that had no purpose other than to belittle another person’s work. Believe it or not, I’ve found that this rule is hard to follow for many writers, because years of rejection and obscurity have turned them into bitter people. We found that rude behavior stopped quickly, however, when other members immediately called people out on their immaturity.

A corollary to our first rule was “Every comment must be constructive in nature.” In other words, members were discouraged from saying something generic and unhelpful like, “This isn’t interesting.” Anyone can make that type of empty comment about any story. Instead, they were encouraged to say something more like, “This isn’t quite working for me because ________. It can be improved by [concrete advice, actual revision in many cases].”

After the rules were first introduced, one workshopper said of a story being critiqued, “I didn’t like the ending.” The moderator said, “And….” The workshopper, realizing that he had violated a rule, then said, “I think what I needed was….[proceeded to give concrete advice on how the ending could be different].” While everyone in the group was an adult who should have been able to deal with criticism, the tone of the comments made a big difference in getting the workshop to turn into a constructive rather than a hostile environment. There is a very fine line between being brutally honest and helpful, and being a discouraging jerk. Generally, the workshoppers became much more receptive to comments that gave a writer a road towards crafting a better story, rather than simply pointing out a story’s weaknesses.

Once our workshop set up some ground rules, someone needed to be in charge of enforcing them. A workshop run out of a school or university has a paid teacher who should be making sure it is running smoothly. Since this workshop wasn’t professionally run, we elected (or more like appointed) a moderator to keep the peace and remind everyone of the rules. If one member was consistently deviating from workshop rules, the moderator was tasked to ask the offending member to leave for the sake of the workshop. While this may seem awkward and painful, one bad apple should not destroy a workshop. Fortunately, the moderator never had to do this, but the threat of it happening had kept people in check.

In another one of my past workshops, the members were engaging in long, pointless arguments over matters of pure opinion. To save that workshop, the members decided to have an “Agree to Disagree” button. We decided that if a discussion was degenerating into potshots or unconstructive comments that were not helping a writer, someone should say, “Agree to Disagree.” If another workshop member confirmed the “Agree to Disagree,” the discussion would move on to a different, more constructive topic. Each member in the disagreement was given one opportunity to speak his or her mind, but then the topic would change. Otherwise, the workshop could’ve degenerated into a Daffy Duck vs. Bugs Bunny “Rabbit Season / Duck Season” debate, which would have resulted in many people leaving.

I’ve also found it helpful to start the workshop with a discussion about why we were all there in the first place. Were we seeking praise? Did we want validation that we could actually write? Or at least write better than our peers in the general metropolitan area? Generally, I think most workshoppers would agree that these are the worst reasons to be in a workshop. The only reason to have a workshop is to improve the writing of everyone in the room. By definition, to improve one’s writing, one has to continue to do it. If a workshop turns into a hostile environment that discourages writers from submitting, it is not improving anyone’s writing.

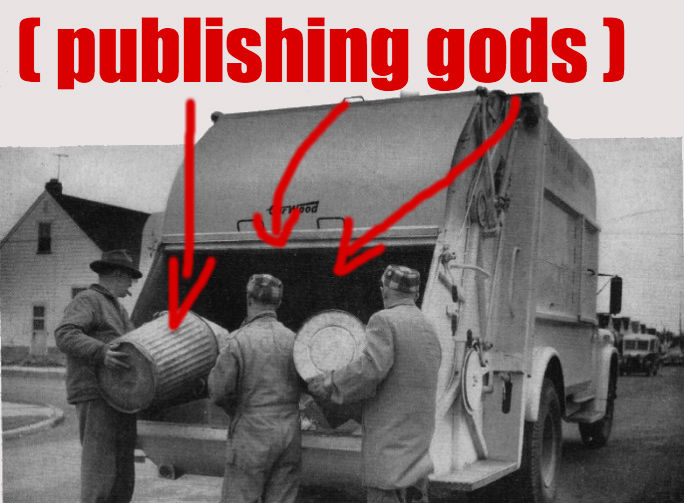

While I’ve just gone over the ways a workshop can go wrong, I should point out that a good workshop is still the most effective tool I’ve ever encountered to improve my writing. When it is going well, a workshop helps me see flaws in my writing I could not have caught on my own. I’m forced to think from points of view that are very different from my own. Without the benefit of good workshops, I would likely still be unpublished and struggling to figure out on my own what was going wrong with my writing. The more problematic workshops gave me thicker skin, but in the end, did not help me become a better writer. If I had only spotted the warning signs earlier, I might have taken early actions to help the workshop be more constructive. Some that were not even worth saving, I probably should not have seen through to the end. Now, if I find that a workshop has many bad apples, and is not likely to improve, I simply leave. Time is far too precious to waste on a bad workshop. Sometimes, it’s best to just walk away.