When Change Doesn’t Happen: School Shootings and the Piles of Novels That Follow

Eleven years ago, months after the Virginia Tech shooting, David Foster Wallace wrote a plea we can trot out at every mass shooting:

Eleven years ago, months after the Virginia Tech shooting, David Foster Wallace wrote a plea we can trot out at every mass shooting:

Are some things still worth dying for? Is the American idea one such thing? Are you up for a thought experiment? What if we chose to regard the 2,973 innocents killed in the atrocities of 9/11 not as victims but as democratic martyrs, “sacrifices on the altar of freedom”? In other words, what if we decided that a certain baseline vulnerability to terrorism is part of the price of the American idea?

If Wallace was still alive, he’d still be asking those questions, as many of us still do. We look at lists of mass shootings in the US from the past ten years alone and wonder when anyone will say, “Enough is enough.” We wondered it when the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School lost so many of their friends in the shooting in Parkland, Florida on February 14, and again when they stood up despite–or because of–their grief to tell lawmakers that this had to be the last time that a shooting happened.

The students have partially succeeded in pushing change. They were initially turned away at Florida senate offices a week after traveling there, but on March 5, Florida’s senate passed a gun-restricting bill; on March 9 Governor Rick Scott signed it into law. It is a mixed bag: while the bill increases the minimum buying age of guns to 21, bans the sale of bump stocks, puts a three-day waiting period for purchase in place, and moves $400 million of the state’s budget to mental health and school safety, it also allows certain school personnel to carry weapons on campuses.

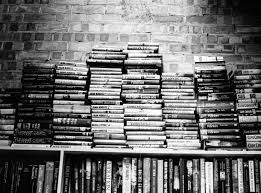

With the frequency of shootings (299 and counting, since 2013), it’s amazing that they register as events at all to Americans. There’s the sense that we’ve become so anesthetized to this level of violence, that we accept it as normal. As such, mass shootings have become a part of our writing consciousness, too. Mostly in the sphere of mass market fiction, genre fiction, and young adult fiction, mass shootings are frequently occurring in the books we read. Since the year after the Columbine tragedy, 2000, a total of 113 novels have been published in English about school shootings. The number of novels published on school shootings before Columbine? One.

A few non-genre novels are particularly memorable: Monday, Monday by Elizabeth Crook (2015) addresses the first mass shooting of the twentieth century at the University of Texas in Austin in 1966; Lionel Shriver’s novel turned film We Need to Talk About Kevin (2003) focuses on a massacre by bow and arrow; the recently released Only Child by Rhiannon Navin processes the aftermath of a school shooting at an elementary school through a six-year-old boy.

Each represents a different take on the tragedy of mass shootings and on their very real human effects, showing us in turn the way that life seems ordinary and normal until the shooting begins, and even then, how we rationalize what we’re hearing is not gunfire but “‘something to do with the Drama Department’” (Monday, Monday), or a popping sound (Only Child) that has no connection to a gun. Reading has the effect of creating empathy where it didn’t exist before, and these particular novels put the reader in the space of being an ordinary person caught in the middle of these events so that we truly understand their horror.

While literary readers normally decline to choose books based on bestseller status, instead often avoiding them, there is value in reading books that are outside of our normal reading purview to tap into what our fellow citizens are clearly responding to. The trauma from these shootings is a shared experience. That these novels have been produced shows that we readers have a need to digest what is happening through books because we’re not seeing progress anywhere else, and because novels are where fiction writers can process the world around them-–a simultaneous act of individual and group therapy.

With each shooting, there will be more books that are produced in response, because that’s what literature and art does: it responds to the worst and the best of our lives to process it, even if this takes time. In the US, we expect to process our feelings quickly and to get on with our lives, but writing is the antithesis of quick, a process all too similar to grief. Though books on the subject are produced slowly, it’s certain that the novels on the subject will pile up as the shooting count grows.

Photo by Lorie Shaull