Guest post by Alicia Jo Rabins

One of the fantastic things about the Torah as a literary work is how it combines impossibly broad swaths of narrative (the world is created, a flood destroys it, etc.) with precise details (Rachel, having stolen her father’s idols and hidden them in a camel saddle, sits on the saddle, pretending she has her period and can’t get up, as her father tears apart the tent looking for his idols).

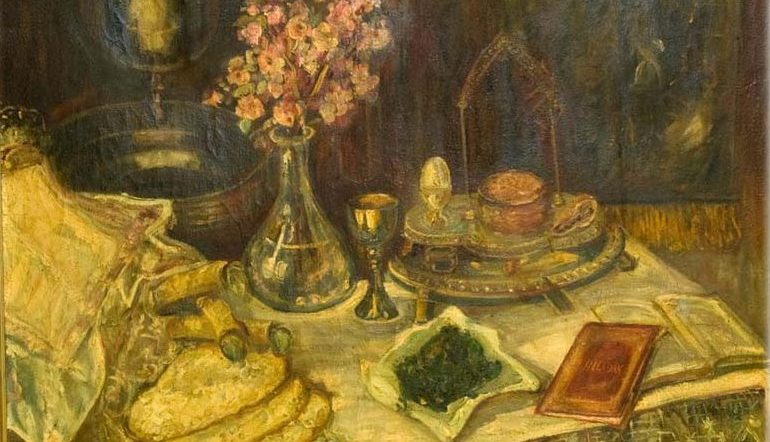

Giambattista Tiepolo, Rachel Hides the Idols, 1726.

For observant Jews, these details are more than merely literary delights; they have real- life ramifications. As I type this, Jews across the world are preparing to replace our beloved bagels, pita, Cheerios, and chocolate chip cookies with matzah for eight days as a result of the commandments to avoid leavening on Passover. And why? All as the result of one of those details: the children of Israel had to leave Egypt so fast they didn’t have time to let their dough rise. They ran through the parted sea with the dough on their backs, baking in the sun, and ate it on the other side: voila, matzah.

Now, when you take a step back, the idea of eating a giant cracker to memorialize a key event in a people’s cultural-spiritual history is kind of funny. But ritual often looks a little funny from a distance. This one seems particularly illogical, though: the original matzah was the result of extreme haste, an absolute lack of preparation, and the point of eating matzah year after year is to re-enact that hasty departure from Egypt*… So is the best way to re-enact that panic and desperation really by munching on mass-produced matzah? In fact, one could ask that question of the entire seder ritual. Seder means order: how can a step-by-step ritualized meal, planned centuries in advance, enable us to access the experience of people undergoing an utterly unexpected, radical transformation?

Enter William Wordsworth. The best answer I’ve found to this question is in his “Preface” to the Lyrical Ballads, where he famously describes poetry’s origin as “emotion recollected in tranquility.”

The tranquility of a writing desk, a page, an unbroken hour, the intent to create: these build a safe container for deep exploration of the emotions that occur, unbidden and unexpected, while we navigate our daily lives. And even though, as you know if you’ve ever been to a seder, “tranquil” might not be the best word to describe the atmosphere, a seder is a poem in this way: a space for recollecting and re-creating a past event, traumatic in its original power, now far enough away to consider. Thanks, Rabbi Wordsworth (sound of WW rolling over in grave) and happy Passover!

One final thought before I return to scouring the kitchen of leftover bits of flour and stale cookies. A key dictum of the seder is that “in every generation, a person is obligated to see him/herself as if he/she personally went out from Mitzrayim [Egypt].” In a metaphorical sense, we are all exiled in Mitzrayim, for the word literally means “straits,” “narrow places.” In other words, we aren’t just supposed to go through the motions, but rather to enact our own personal exodus from our internal oppressions and limitations–and, I might add, to think about the ways in which we might be oppressors of others.

Both writing and ritual traffic in symbols, but the work we do is real. The force field of tranquility surrounds the dangerous emotion and allows us to enter it. This is powerful magic.

When we are able to perform our creative and spiritual practices freely, they can seem gratuitous–scribbling on a page, munching on a cracker. Most of us in the United States are lucky enough to be in this situation. But when political, familial, or religious oppression attempt to prevent us from writing, speaking, or performing rituals, it becomes clear how essential these modes are, for it is here that we do some of our deepest work as artists and as humans.

*To be fair, matzah also represents humility, and abstaining from leavening–a rising agent, which puffs things up–is a symbol of consciously deflating our egos for eight days. But that’s a different blog.

This is Alicia’s fifth post for Get Behind the Plough.