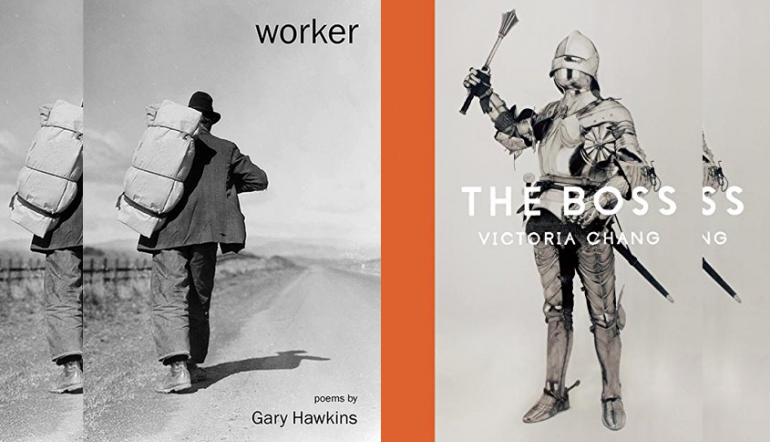

Worker by Gary Hawkins, The Boss by Victoria Chang, and the Exploration of Work in Poetry

If you wanted to trace the history of American poets writing about work, there are a few touchstone poets you might turn to. While the European modernists cast a wary eye on anyone not living the life of the mind (even as Eliot turned on his banker’s lamp each morning in London), American modernists were writing about labor extensively, from Whitman’s shoemaker and Frost’s fence-mender to W. C. Williams’s poems that allude to his experiences as a physician. Despite this lineage, and despite America’s inherited obsession with work and work ethic, there don’t appear to be many contemporary poets writing much about working. Perhaps the poetry of work changed as the field became more intertwined with academia—with so many poets teaching (one of the more rare professions explored in the genre), it became common to see poems set in classrooms. But the tide seems to be turning back, perhaps because academia is in a crisis, perhaps because capitalism is. Two recent books, Worker by Gary Hawkins and The Boss by Victoria Chang, offer two ways of writing about jobs.

On the cover of Gary Hawkins’s Worker is a black-and-white Dorothea Lange photograph of a migrant worker. The photo was shot from behind, with the worker walking in sturdy boots down a dusty road with a pack on his back. In Hawkins’s volume, many of the poems touch upon menial or manual occupations: the waiter, the stevedore, the prison warden, the maid. These are persona poems, but the poems don’t feel as if they are costumes that Hawkins puts on to milk the symbolic resonances; rather, it feels that the intelligence behind the poems slips into the consciousnesses of these workers by assuming their most central tasks. In “Homebuilding,” the act of building a house dovetails with the making of an intimate relationship: “I lifted rafters to branch our bedroom. / Each gable watched the roads that would bring you.” In “The Warden, Admiring Dogwoods,” an imperious warden listens as his dogs attempt to recapture an escapee. Businessmen tie their ties; fishermen tie their lures.

Inevitably, in the tradition of Seamus Heaney’s much-anthologized poem “Digging,” understanding the tasks of these various workers brings the speakers back to the labor of the writer. In the delicate poem “The Mason,” the speaker begins the poem by acknowledging his failure: “I am staring at the ruin / Of some yet unimagined temple.” He cannot seem to build, whether “wall” or “hearth” or “altar”; by the poem’s end, he declares:

Dear father, pity not me

But the stones, dry words we know.

I have gone in search of safety,

Bricks, the square refrains of songs.

This turn toward poetry is not, as in Heaney’s piece, a refutation of manual labor but an argument that poetry is a kind of building, a solidity of materials, the patience of laying a piece down word by word. Formally, tonally, these poems are far from the sprawling exuberance of Whitman, though their spirit of quiet generosity is clearly kin to the nineteenth-century master.

Where Hawkins moves among the workers, Chang examines the power structures that separate the workers from the bosses. Where Hawkins honors the connections made between workers of all kinds, Chang is more interested in the divisions that separate the powerful from the powerless.

The boss figure is what makes Chang’s poems about work so unique. If Hawkins’s workers struggle with their materials or the limits of their strength and stamina, Chang reveals a different antagonist through the figure of the boss, firing workers at will and propping up the corporation. It’s also unusual to see poems about white-collar workers. Chang’s book may not be the first of its kind, but it’s almost certainly the best.

Chang’s style is unusual too, aggressive in wordplay, her words tangling through a lack of punctuation and repetition. The figure of the boss looms in every poem, set at the heart of the poems’ sonic briar patches. “The Boss Has a Band of People” begins: “The boss has a band of people around her the way / a band bends around her finger the boss’s / husband calls her a Rottweiler.” This associative leaping is characteristic of all the poems here: the boss’s posse, or band, becomes her wedding band, her marriage a reflection of her rather savage personality. And if the boss is a Rottweiler, then the worker is prey:

I jumped into the water the Rottweiler

[space]swam its mouth open forty-two rottingteeth tongue out I jumped from the water looked

[space]at my own wagging tail my Rottweiler topcoat

[ ]of black the boss behind me clothes dripping …

The speaker as a dog running into the water to get away from the pursuing boss, the human and dog morphing together in the dripping clothes, the open mouth with too many teeth, the furry coat, the wagging tail, the boss finally “panting smiling putting her fogged // glasses back on”—this moment is terrifying. Both the boss and the worker are hybrid creatures, part human, part animal, locked in a relationship where the hunter and the hunted must wear smiles and exchange pleasantries through bared teeth.

While Hawkins and Chang have their differences, they both write devastatingly of fathers in their volumes. Hawkins makes repeated references to a father who was skilled with his hands and who mocks his son for being less talented, while Chang’s poems weave the figure of the boss with that of the father—in this case, one who is suffering from dementia, his productive power in the workplace elegized in tandem with the man he was. In these depictions, it’s clear that work resonates across our identity—that it is bound up with our families, our politics, our sense of self. We are what we do for a living, and that is both something to celebrate, as Hawkins does, and something, as Chang does, to push against.