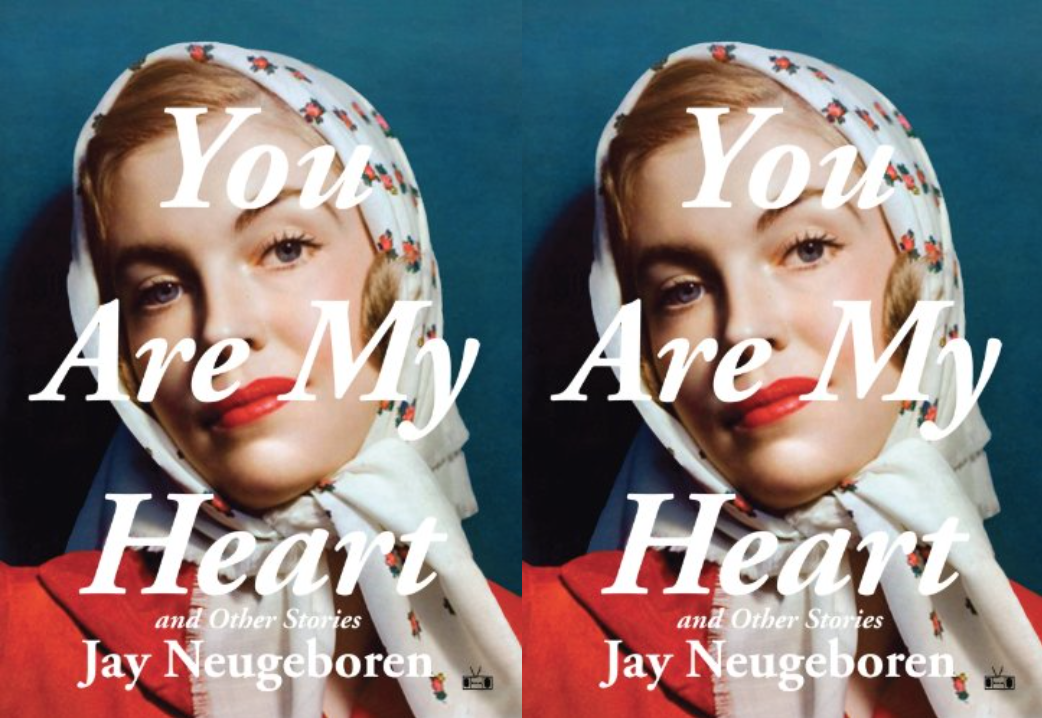

You Are My Heart

You Are My Heart and Other Stories

Jay Neugeboren

Two Dollar Radio, May 2011

194 pages

$16.00

All authors have subject matter to which they constantly return, consciously or not. For Dickens it was the lower classes, for John Irving it’s small town New Hampshire—and for Jay Neugeboren, in his new collection of stories, You Are My Heart, it’s boomers visiting rural France to escape unsatisfactory lives in America.

That’s not quite as reductive as it sounds, and each of the characters in the collection’s many France stories do possess a fleeting individuality. But I get the sense that the echoes are not wholly unintentional. Every time we return to the setting—a string of tiny villages in the French countryside, through which we’re driving, always driving—it feels a little more familiar, transforming the setting into an odd sort of literary purgatory in which the characters, ghosts of their former selves, confront their past mistakes but never each other.

Not all the stories in You Are My Heart fit that mold, however, and the collection’s bookends—Neugeboren’s finest work, here—reveal a very different preoccupation (or perhaps an earlier iteration of the same one): young men coming of age in postwar New York.

In “Lakewood, New Jersey,” we follow the narrator, Marty, as he slowly outgrows one unsuitable idol—his alcoholic, adopted cousin Joey—and falls in misguidedly with another: his boss at a New Jersey prep school, Margaret, with whom he has a brief, romantic entanglement. We know it can’t end well, of course, but Neugeboren imbues Marty with enough naiveté, and distracts us with enough other plot threads, that we end up believing it will—which makes his confused frustration at its demise all the more affecting.

In the other bookend, the collection’s title story, the narrator is a Jewish teenager in 1950s Brooklyn, a high school basketball star and aspiring architect. For reasons more plausible than you might think, he ends up joining a gospel choir and falling in love with a (black) girl he meets there, making his coming of age a much more expansive one—as much about struggling with race, religion, and class as about first love or outgrowing one’s parents.

Talk about knowing it can’t end well! But this time the disaster unfolds before us, unmitigated by any other subplots and in all its doomed glory. And perhaps it’s doomed glory, more than boomers in France or young men in fifties America, where Neugeboren seems most comfortable of all.