And I Saw Myself Running

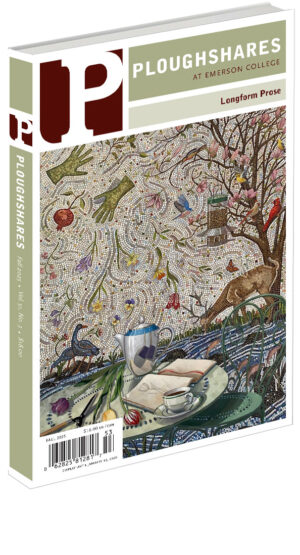

Issue #165

Fall 2025

Translated from the Hindi by Daisy Rockwell “At exactly two o’clock, take a look at your watches,” he announced. “Right when the clock strikes two, I’ll pass on.” A tone that boasted of his all-powerful lineage. He could lift people...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.