The Cacophobe

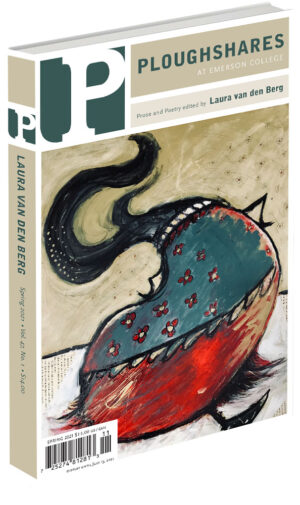

Issue #147

Spring 2021

There’s a secret buried in this letter. What I’m about to tell you isn’t it: I am deathly allergic to ugliness, I have been since I was a boy, and by the time you read this, this affliction, which has...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.