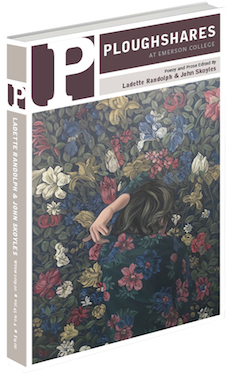

Creation (Emerging Writer’s Contest Winner: FICTION)

In fiction, our winner is Ruby Todd for her story “Creation.”

Of her story, fiction judge Ottessa Moshfegh said, “This exquisite story about a struggling sculptor was obviously penned by a seasoned conjurer of art and prose. It rings with the truth and precision of memoir, and sings in the peculiarities of magically timed fiction in its feeling and movements. And it is funny.”

Todd is a creative arts researcher, teacher and writer of prose and poetry, currently based in Melbourne, Australia. Her work has been published in Overland, TEXT journal, Qualitative Inquiry and Meniscus, among other venues, and her fiction has won the Chapter One Prize of the Australasian Association of Writing Programs. She holds a PhD from Deakin University on the subject of elegy, and continues to be interested in the connections between loss and creativity. She is currently working on a novel, and a work of narrative nonfiction.

When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

I think when I was around six or seven. I’d always loved being read to, but that was the point when I remember discovering the delight of metaphor, the wonder of language as a tool to capture states of emotion (and then to describe these states to my parents, which was surely equal parts comical and insufferable). The idea of making something, of creating a bright little world in the form of some pages between two covers, also struck me early on as magical. I think I’d always been aware of time as a passing force and as a source of loss, that records such as books might help in some way to redeem, even if only for their author, as in the case of personal diaries. One day at around six years old I decided to “write a book” about Queen Victoria, with whom I was quite taken, perhaps due to our charming Anglophile neighbor who was lovely to me and baked delicious biscuits. I went next door to speak with her for ten minutes as research, and then went home to work on the words and pictures.

What is your writing process like?

I try to write every day, in the morning preferably, as despite not being inclined to cheerfulness at that time, it’s when words flow best. Besides, if I write first, I tend to be a more generous and patient person for the rest of the day. My process involves a cup of tea and usually some kind of repetitive minimalist piano music. That might sound pretentious, but I find it helps me access the rhythm and tone of the day before. Beginning a new piece tends to involve probing some element of growing obsession further until it begins to suggest a narrative shape. I’ve always loved Nabokov’s description of feeling a work’s generative spark as “the first little throb.”

On a broader level, while my process has always been quite intuitive and organic—that trial and error while peering through the dark that many writers discuss—I’ve lately been experimenting with prolonging the initial ruminative stage before writing the first words of a new piece, and then setting down a kind of skeleton in notes first, which then becomes a kind of constraint, and I’ve found this to be a fruitful change.

What inspired “Creation”?

“Creation” emerged out of a kind of dialogue with myself about artistic failure, and the question of what such failure costs and, perhaps more interestingly, what artistic success really constitutes. These were questions I myself had been asking before I came to write it, after a difficult period in my writing. The narrator desires for her sculpture some measure of external validation, if only so she might be permitted an audience with whom to share her work, and without whom she senses her creations will never truly live. I think this is a sentiment many artists might relate to having felt at some stage in their creative lives. In the formal struggles and crises of confidence that beset many artists, especially early on and especially in moments when the hallmarks of external success might seem elusive, the question of whether to continue with art and whether it’s “worth it” often rears its head. I’ve noticed that at such times, art can begin to feel like an absurd compulsion, a kind of self-cannibalism or replacement of real life that might constitute a form of madness. To me this felt like an interesting and perhaps cathartic kind of test to explore in a story, because such moments in my own life have ultimately always served to clarify my commitment to the work itself. Such moments have for me, as for the narrator, also served to make me question in fruitful ways what authoring a work really entails, what it means to be haunted by the creations of earlier artists, and how to ultimately find and make space for your own voice.

On a simpler note, I’ve always had ekphrastic tendencies and love writing about visual art, and found myself writing “Creation” at the tail end of a long project, which also had sculpture as one of its subjects.

Who are you reading? And who informs your work?

I just finished reading Sarah Manguso’s intimate meditation on diary writing, Ongoingness: The End of a Diary, and appreciated her explorations of the connections between writing and the losses of time. I also recently completed the final installment of Rachel Cusk’s wonderful Outline trilogy, and am still struck by the immersiveness of its atmosphere, and by how widely the narrative ranged while holding the reader within the sound of its singular, dry-witted voice. I’m now halfway through Jeremy Reed’s biography of the fascinating English writer, Anna Kavan, A Stranger on Earth, who is a new discovery for me.

Some of the writers who continue to inspire me include John Banville, Vladimir Nabokov, Marilynne Robinson, Marguerite Duras, W. G. Sebald, Wallace Stegner, Anne Carson, Jeffrey Eugenides, Daphne du Maurier, Patricia Highsmith, and Elizabeth Smart.

Do you have any advice for new writers?

I’m not sure I have any advice to offer that’s very new; what occurs to me has been said many times before—read and write, keep going, and write because the writing is first its own reward as there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to make a career of it. I think something I wish I’d been told years ago is that, despite the standard adages, just because you identify as a literary writer doesn’t mean some degree of advance planning is somehow incommensurate with the form and style you work in. I think many writers who don’t plan to some degree in advance might assume it’s the most authentic method generally, in terms of inviting unconscious influence into the early stages, but also underestimate their own deftness for structuring and plotting along the way. Because I tend to be quite detail-oriented, and focus on building a narrative on the level of small images and immediate, individual moments in time, I’ve found recently that approaching a long-form project with a more distinct stage of pressing out the lineaments of an outline—which I can then work within on that more micro level, even as the wider shape shifts and continues to surprise me—is quite freeing.

What projects are you working on now? Where is your writing headed?

I’m currently in the midst of writing an oddball psychological thriller with astronomical themes, set between the US and Australia at the turn of the last millennium, while also revising a completed novel manuscript. I’m also working on a manuscript of narrative nonfiction that explores some of the themes of my previous doctoral work in a more open-ended and playful way, relating to the different ways we navigate the limit that death, and other more contingent kinds of loss, represents for the living, especially in the context of our present climate and ecological emergencies.

*

Decades ago at the start of a Melbourne autumn, my friend Sara invited me to a party. I don’t like parties—she knew this—yet still I heard her bright expectation on the other end of the phone. I’d been watching the street darken through the window when she called, and as she waited I lurched around silently for an excuse that didn’t sound like a lie. “We’ll have to go shopping for outfits,” she said when I finally agreed to go, as though this would be part of the fun.

Back then I was working in an office that smelled of old carpet, as a secretary for an Ear, Throat, and Nose doctor whose orders, issued in a thin, pained voice, echoed in my mind when I wasn’t there. I often wished I’d had the foresight to train for another profession—something unassuming yet autonomous, like archiving or copyediting. But in quiet moments, it was the life of the nuns in the brick building opposite mine that I longed for, the building’s blinds always drawn like eyelids against the day.

In my real work as an artist, I seemed to be failing, but couldn’t have stopped my sculpting if I tried, which somehow made the failure worse. As if to punish myself, I filed each piece away in plain sight on my long workbench under the window that looked out at the nunnery. My creations would eye me as I drank tea in the mornings, an audience at once indifferent and resentful. At other times, they would form a kind of company and look out with me at the neat figures of nuns on the grounds, whose heads always seemed inclined toward each other in serene conspiracy. How wonderful, I would think, to believe in a creator being to whom we all returned.

At ever-increasing intervals, I would attend shows by friends from art school whose work had met with some measure of success, and eat cheese with them. I would wonder whether they believed I had attended in order to benefit from their connections, and wish that feeling pleased for them were not such an effort. Then I would stay up late, warring with a block of clay to focus my attention to its stillest point, pressing out the contours of some face I had seen or dreamed, hoping it would prove the exception to the disinterest my work had elicited from gallerists and dealers in town.

While the face or figure was still emerging under my thumbs, everything would feel possible, as if I were solving the final alchemical riddle. Some afternoons, the living force of the clay seemed to fill my blood with light, at other times it felt like a kind of birth. Even if the result was disappointing, I had the labor—more and more, I saw that this was what I lived for. But my hope was brazen; each block I cut lifted my sails for a few days. To preserve this feeling, I would sometimes abandon a work while its features were just appearing. Yet these abandoned works, too, were disappointing, as if without the warmth of my moving hands keeping their fate mobile and pointed toward the future, the promise that once had been visible died. This death was more devastating when I carried a work to the final stage: it emerged into the room with me, open-eyed; we looked at each other and I saw not only that it was dead but also that it had never lived. I would lay it to rest alongside the other half-dreams and register in my body another kilo of phantom weight. Then I would wish not for success but to relinquish the desire for an audience, which shadowed truer things. I would see some awful story on the news—a mudslide in Bangladesh, or a child murdered by a man with lizard eyes—and recognize my absurdity.

On the Saturday before the party, I met Sara at Myer. I trotted behind her like a lady-in-waiting, bundling dresses under my arms. I remember finding the colors of that season too bright, the fabrics too harsh, the shapes too boxy. Sara tried on dozens of dresses, squinting at her reflection and then at me with desperate seriousness, and sighed when I suggested they were all quite nice. Bored and longing for an ice cream from the cafeteria, I suggested she try on a simple crepe tea dress I had noticed hanging on the returns rack, in a mulberry color, which would suit her pale skin. She only plucked at the fabric with a scowl when she tried it on, finding it tight at the bust and too plain.

“Give it to me,” I said finally, trying to hide my frustration and aware that owing to wearing only pajamas at home and avoiding outings like these, I, too, needed something new.

She raised her eyebrows when I stepped out of the change room. We peered at my reflection in the mirror as I turned around, looking for a weak seam or misplaced dart. The dress enclosed me as if a tailor had measured it. My face in the mirror looked more vital somehow, as if it knew something my real self would discover only if I bought the dress.

“I think this will do,” I said, feeling a strange heat on my chest just under the sweetheart neckline.

At the register, I asked the sales assistant to remove the tag of the dress while I was still wearing it. After saying goodbye to Sara, I walked along the river in a daze, arriving home only to descend into a dreamless sleep.

2

I woke with the sun, posed as I had collapsed the day before, straight as a mummy with a strange tingling on my skin. I showered and put the dress back on. In the mirror I peered at my face and wondered whether the pink in my cheeks foretold good health or a coming fever. Standing in front of my workbench under the window, I looked outside in the avenue at the plane trees, which seemed to have turned yellow overnight. I looked at my languishing clay creatures and was surprised to feel no weight of sorrow or dread. With less forethought than usual I sat down, sliced a block from the terracotta slab, and descended into the strange half-sleep of making, in which my fingertips took on the function of sight.

Usually I had an idea in mind—a boy I had seen on the bus with a wistful expression, or a woman at the supermarket with a marvelous number of chins. Sometimes I would flesh out figures at speed to see if I could lose some of the stylistic preciousness of which I had been accused. I imagined finding a brand of economy as elegant as Giacometti’s attenuated forms, or as satisfying as Paleolithic artifacts with their strange, lumpen poise. But I would pause and second-guess my hands, and my speed figures would look confused and overwrought, as if to spite me. Regardless of my efforts, every work I made betrayed my love of the Roman bust: fine detail, correct proportions, earnest gazes. I had perfected hair in a series based on Flavian Woman, for which my mother sat for hours in a wig while watching reruns of Prisoner. I would listen to entire classical albums while erasing evidence of my fingers with alcohol and fine brushes. I ruined a lot of work this way.

That Sunday, it was as if the nerves of my hands worked apart from me, while my eyes paused for long moments on the plane trees outside, observing the emerging shape only from a blurred distance. With an empty mind, I enjoyed the slippery coolness of yielding clay, its loamy smell of earth quarried somewhere far away in France. When at last I paused and focused my eyes, I saw a woman’s face looking at me with careful attention. It took a while to register my surprise, as I felt I’d been dreaming. She was middle-aged, with a high forehead and strong nose. She seemed to have a shock of wiry hair swept back. I noted that my lack of conscious attention in sculpting her had led to a swift, mobile confidence of form that was never a feature of my careful, methodical style. I stepped back from the face, and peered at it from a distance as I made coffee. I half expected her expression to have changed when I returned, but it was the same: a measured expression of the mouth that might precede a realization, or smile. “Who are you?” I asked. I was enjoying the feeling of surprise, even if it was of an unnerving kind.

I felt as if I were overheating, and left to walk a few blocks for fresh air. When I returned she was the same as before, and I considered that perhaps I had awoken in a strange mood that was affecting my judgment. I ate a sandwich, thinking food would steady me, and took a painkiller as I had a headache. Eventually, I sat back down. As if we were being watched I affected an air of disinterest toward the face, and without meeting her gaze, deposited her at the end of the line of other faces.

I cut another block. La Traviata began playing on the radio, which somehow quelled the atmosphere of expectation. I began with slow deliberation: I would model my father’s face. It was only once I had marked out his eye sockets and cheekbones that I began to relax, recognizing them as correct, feeling the music fill my chest. After a while, I opened the window to let in a breeze. By now I was smoothing out the eyelids, finding myself looking out the window again. Finally, I registered that my attention had strayed, and jolted. It wasn’t usual for me to grow so distracted while sculpting. I looked back at the emerging face, and felt a cold heat begin to spread. I was no longer looking at my father. The face had become strange, the face of someone I’d never seen. He was about the age of my father, but there the resemblance ended. His fascia was craggy, his cheeks sunken, his brow bone pronounced. I sensed he would have a sharp, clever gaze when I fixed his pupils. I wondered whether I was hallucinating. I set the man’s bust by the woman’s, to the far side of the table where I had to strain to see them. I draped them both with cheesecloth and then fitted each with a plastic bag to ensure an even dry. I wondered whether to destroy them. I was frightened of looking away, in case their faces continued to develop and change without me and I’d have further cause to doubt my own mind. The light was fading now. Exhausted, I went to bed.

The next day, I attended work in a fog. Dr. Heiss had back-to-back bookings all day.

“You look flushed,” he said without expression when I set down his coffee. His observation didn’t seem to require an answer as he had already returned his gaze to his appointment schedule. I said nothing, and detoured to the bathroom on my way back down the hall. I couldn’t tell if my face was flushed as the light was unnaturally yellow, but I did look mildly stunned.

The day’s appointments rolled by: a deviated septum, an ear infection, chronic sinusitis. At the desk in between patients I worried the rash on my chest was beginning to welt under my blouse. I wondered whether it was allergies, and whether I would have to miss the party after all.

At midday, Mr. Rodriguez appeared for his tonsillectomy. As I looked up and smiled and started greeting him in the usual way, I felt as though my mouth was suddenly moving apart from my brain, as shock dawned and I checked his features to disprove the impossible fact that his was the face my blind fingers had made the afternoon before. He didn’t seem to notice my conflict. He clutched a sheaf of papers, smiled cautiously, and bit his lip. No one looked forward to appointments with Dr. Heiss. As Mr. Rodriguez read the paper in the waiting room, I tried to convince myself that I had conjured his face because I had seen him before in passing, even if I had never summoned his face consciously since. I checked the appointment book to find the date of his initial consultation, January 4th, and felt somewhat better.

I had lunch at a café, watching the stream of people on the sunlit street instead of thinking about Mr. Rodriguez, and wiping my nose with serviettes. My eyes were itchy, the light too bright. I wanted to go home and draw the blinds.

On Friday, I called in sick. In the dim morning, I sat by the window, short of breath with blocked sinuses, although the rash on my chest seemed to be healing. The flat had a furtive feeling, as if I’d caught it out in its expectations for a day without me in it. My eyes slid over the row of heads, arrested and disembodied like the remnants of some small-time dictator’s genocide.

I was a comparatively lazy sculptor, preferring the ease and immediacy of working from a solid block that I’d then hollow out. I didn’t like the calculated beginnings of the cylinder technique, and whenever I used an armature, I was always too anxious to ensure the resulting work validated the effort of screwing a flange and board and scrunching up all that newspaper. Although I dreamed of one day mastering bronze and iron casting, I loved the immediacy of clay, its earthen smell, the sense of my own body wrestling another into being. I low-fired the ones I liked and used patinas, oxides, and resins to create a look of age. At that time, I was experimenting with black oxides to mimic iron, and had begun to paint the eyes in the Roman style. But I needed a trademark, a shtick. Many successful contemporary sculptors of a classical bent seemed obsessed with mythology and monsters. Medusas, hermaphrodites, chimeras, and grinning things with horns all seemed to do well, reconnecting the public with the tradition of Etruscan monsters in work that was often far less sophisticated than the originals they were inspired by. But art rarely responds to reverse engineering for the market, and the market didn’t need any more technically proficient Medusas. I could think of few alternatives, seeming to lack the gift of narrative invention. I wondered whether this meant I was a craftswoman rather than an artist.

Because I hadn’t bothered firing or casting or making a mold of anything for months, some of the heads I’d left uncovered had begun to crack. I imagined hurling them all through the window to shatter on the road, so that when the nuns went out to buy milk they would have to step over noses and ears and bits of skull. I tried to imagine it, but couldn’t decide whether they would be horrified or amused. I wanted to believe they’d be at least intrigued, and glance up at my window with wondering expressions.

Looking at the heads, I questioned whether there were any worth firing at the community kiln studio. I walked over to the two new heads and lifted their coverings. I peered at Mr. Rodriguez, for it was indeed him, and at the wire-haired woman, those faces that seemed to have appeared without my intervention a few days before. I touched a hand to the woman’s cheek, and figured she was dry enough. I decided to fire her, if only so I could reassert control over the strange way my practice had run away from me, and so that I could try a new satin-hard glaze.

As I walked through the park that led to the studio, carrying the head in a padded hatbox, I began to feel hopeful. Perhaps this head would be a success. Yet it was difficult to feel attached to a work that didn’t seem to have required me for its existence. There was a bench outside the studio, and as I passed it I wished I could just sit there in the dappled light instead, without ambition or concern for the future.

The surly attendant didn’t look up when I entered. She was instructing a woman with coiffured hair and peacock earrings on how to operate one of the potter’s wheels, guiding her hands as they laughed. I had never seen her so animated. I signed in and took the hatbox over to the bench by the kilns where I pulled out the head and rested it on the bench in its wrappings.

Eventually, the attendant came over. “Here for the firing?”

I nodded.

“OK, get it ready to put in.” She gestured to the head before stalking over to the kiln and fiddling with the trays.

“Only just bone dry,” she said when I handed it to her, regarding me with the muted look I imagined she reserved for most artistic frauds. Then, for some reason just as she was about to set the head down, she looked at it—something she never did—and then looked at me.

“Was this modeled from life?” she asked, frowning with real curiosity.

“No,” I said, puzzled, and asked what she meant.

“It’s Cynthia Lerner, isn’t it?”

She sighed when she saw my blank expression.

“The sculptor. She did the bog series? Anyway, she died a few weeks ago. This is the spitting image of her.”

I wasn’t able to speak. After leaving the head with the attendant, I sat in the café next door, looking into my coffee and feeling dizzy.

3

Instead of planning the colors for the glaze that evening, I went to the library. I worked through the previous fortnight’s newspaper obituaries until I found Cynthia Lerner’s, alongside the thumbnail photo I’d been hoping for. It took my tired eyes a moment to adjust. Then, there she was; the image of Cynthia Lerner and the image of the clay face I had made, converging as I stared, like a death mask over its model. I wondered what it all meant. Unlike Mr. Rodriguez, I was certain I had never seen Cynthia Lerner before. A librarian helped me to find an old catalog of her work, and as I flipped through its pages, I realized that the style in which I’d made the last two heads was her style. I squinted at the catalog images and saw the same swiftness of form, the same half-finished features. Lerner was a master of suggestion. She knew when to stop. Her figures and busts seemed always to still be emerging from, if not trapped in, the clay they were formed from. You could see the tracks of her fingers and thumbs—faces and limbs were formed from smears and divots, a thick, roiling surface. Her most famous work, for which she had won the National Sculpture Award, was a series of prostrate figures in bronze, based on the bodies found throughout the centuries in the bogs of Northern Europe: Tollund Man, Grauballe Man, Lindow Man, Yde Girl. I’d marveled at photographs of those bodies myself, appearing as they did like readymade sculptures, their burnished peat-preserved skin softened and wrinkled like overworked clay. In 1950, Tollund Man’s head emerged from the bog separate from his body, wearing a pointed sheepskin cap and the noose used to kill him in the Iron Age. Otherwise, he looked like a man asleep, with beard stubble and the wrinkles of late middle age. Lerner didn’t try to replicate the forensic detail of these real bodies. Instead, her bodies looked as the originals might have while still covered in peat, before archaeologists had revealed the finer details of their flesh.

On Saturday, I collected Cynthia’s head from the studio and glazed it in a conscious imitation of her mature style, using a green oxide wash to imitate bronze. When it was finished, I took it to one of the better galleries in town, run by a man I had attempted to see many times and whom I had begun to imagine as a shadowed, imperial figure like the perpetually absent masters of old European estates, whose names haunted their houses and servants. One of his artists made Plasticine figurines of monstrous humanoid figures variously eating, fucking, or giving birth to each other. Another made silkscreens of his Scottish Terrier superimposed against backdrops by old masters—Velázquez, Bosch, Titian—while ripping off the style of Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych shamelessly. Both were hits at home and overseas. In my darker moments I imagined them all colluding in some art-world version of the Knights Templar.

Once I had scanned most of the back catalogs and drunk too much water from the cooler, the receptionist informed me that the gallerist’s assistant would see me. Eventually, he ambled out from his office into the reception area, a bearded Irishman in a lime green shirt. In his office, like a supplicant after many failed harvests, I handed him the head in its box. Without expression he peered in, drew it out and looked it over, while I observed an abundant vase of yellow tulips that were just beginning to turn.

“Lerner, isn’t it,” he said, in the same expressionless manner. “A portrait—and an homage to her style.” He looked at me with narrowed eyes. “OK,” he shrugged. “Send photos of more work.”

He reached out his hand for me to shake, and that appeared to be the end of it. I wasn’t sure what to feel.

Walking home, I realized that the portrait of Lerner was a trick I could play only once. Simply imitating another artist’s style over and over across a variety of different subjects, without variation or irony or critique, was the realm of plagiaristic kitsch. Even if I could, I did not want to sell souvenirs. Yet none of my previous work was suitable to photograph. Somehow I needed to make more work in a style consistent with the previous two heads, the style of Lerner. Each evening for the following week, I sat down to work, invited the strange trance out of which those two heads had emerged, and then proceeded to make work in my own dependable, unsellable style.

By the next Saturday, the day of the party, I was exhausted. Only my affection for Sara propelled me there, wearing the dress and a far too cheerful shade of lipstick. All my remaining energy was spent pretending I was enjoying the crush of people and their banshee sounds, the bludgeoning music, and the flavorless fried food that was meant to justify the price of the ticket, for which I could have bought a good number of oxides and Mason stains. Eventually, just after midnight when a nice-looking man and his friend got talking to us and I could see that Sara was deep in a mutually enjoyable conversation, I was able to kiss her goodbye and leave with a good conscience.

Back home, I felt strangely awake. Looking out at the dark street, I had the idea of staying up to see the dawn. To pass the time, I thought I’d try to make another head. After my recent failures, I had no expectation of creating another Lerner. Then, having spent an hour or so roughing out the main features, I realized I’d been looking for a while at the lights of the nunnery while my hands had kept moving. Looking down, I saw the emerging face of a young girl smiling, made in the style of Lerner. Finally, I asked myself what conditions in that moment were the same as they had been last time, and it occurred to me that it was the dress. In front of the mirror I removed my art smock and pulled the dress from my shoulders. Peering at my chest, I saw that the redness followed the faint line of the sweetheart neckline. It didn’t make sense. I couldn’t fathom the apparent connections between my sculpting, a dead artist, and an allergic reaction to fabric.

Every night for the next week, I wore the dress as my nose ran and my chest welted. I made bust after bust in Lerner’s style from a cylinder base. It was almost mindless, a trick my body knew when wearing the dress. I built up a cache of them over days, like bullets to be deployed. When I realized I had enough, I took off the dress and eyed the busts for hours in the comfort of my pajamas, wondering how to make them my own.

For several nights as I recovered from my symptoms, I couldn’t sleep. I would doze off and find myself in Surrealist nightmares—among giant marble heads in shadowed public squares; being chased by Gorgons in ruined cities. On one of these nights, I rose from bed, walked through the half-light to my workbench, and picked up a wire-ended tool. I lifted the plastic from one of the busts, a well-formed young man whose head was downturned in thought, his mouth suggesting a smile. Squinting and quick in an effort to beat thought, in a single motion I sliced the head in half. The right side fell onto the bench, leaving the left still attached to the base. The wire loop left a deep uneven gouge on the side that still stood, exposing the head’s hollow interior. There was something austere and satisfying about this deconstruction. I felt something lift in me as I looked at it. I tried the same technique on another head, this time cleaving away each side so that just the middle section was left. I realized that I could reveal this negative space in an infinite number of ways. I could break the heads after firing and reassemble them with missing parts. I could mount sections of their faces on walls, to create the simultaneous suggestion of appearance and disappearance. I could create an installation of fragments.

A month later, the gallerist’s assistant agreed to include one of the shattered heads in an upcoming emerging-artists’ show.

I didn’t wear the dress again, but neither did I discard it. It hangs in my wardrobe still, a reminder of something uncertain.