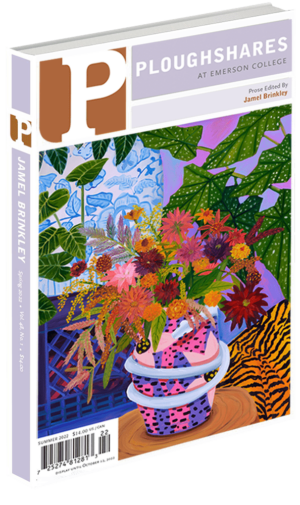

The Dead Zone

Issue #152

Summer 2022

1 So this your real, ehm, body? The real you? No silicone for Ms. Velvet Lace? I say it’s really me, of course. I say it pleasant as can be, like I’m still working the register at Key Food, even...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.