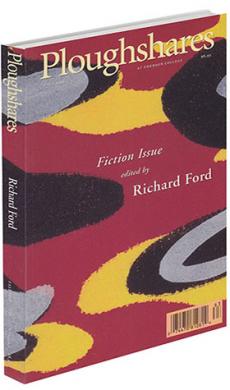

Introduction

If you don’t like these stories, you should’ve read the ones I

didn’t take.

Even though that’s not accurate, it’s probably the only thing I could say in this space to truly arrest the attention of the curious soul bent on simply reading a few good stories (which, in fact, he/she will find here). But, after spending months reading, and wrestling with one’s “tastes,” splitting one’s own hairs, urgently writing friends to send their work or the good work of their students, mulling self-importantly over the state of the American short story, the American literary magazine, the combined fate and character of the young American writer-in-training, plus one’s own dubious fate, enmeshed as it precisely is in all these just-mentioned occupations — after doing all that and actually coming up with quite a few good stories to show for it —

to then face the “need” of an introduction, seems, well . . . slightly awkward. Perverse, even. Unnecessary. A bit like putting a wiseguy vanity plate on a rental car: humdingers!

But, what

should one say? Should I yammer on about what’s good about these stories “taken together” — concoct some obscure,

ad hoc category they either fully satisfy or invent anew, flattering thereby myself, the closet critic, and possibly also tripping up the stories themselves by making them bend even more lowly to my will? Good stories want only to create their own special terms each by each, satisfy them richly, and be done with it. A category of one.

Or maybe I should plot out my own well-burnished definition of what a good story Platonically

is. Though that immediately risks ruling out something unforeseen and wonderful: a fresh new Donald Barthelme, for instance. So that wouldn’t be a good idea. (The critic’s job

is a hard job.)

It’s squeamishly tempting, only for the “sake” of the anonymous young writer, of course, to offer a short treatise on why stories (such as the ones I didn’t choose) failed. How they attained what I saw as their inadequacies (lack of authority, lack of clear narrative voice — whatever that is — on and on and on). But who cares? Plus, as soon as I got my famous treatise all laid out neat, the last story I rejected — the classic of all unsuccessful stories — would show up in

The New Yorker, win an O. Henry Award, and I’d start getting smirky letters with Iowa City postmarks, “thanking” me. Once, when I was teaching at Williams, a poet colleague and I thought about offering a course in which we would anatomize bad novels for an entire semester — again, all for the benefit of our writing students. For some reason, this seemed likely to be instructive. Only, we couldn’t make ourselves read through our own syllabus, which

was instructive, and we quickly forgot about the whole idea, following the wisdom that only good work counts.

Another possibility might be to enter mincingly into my own autobiographical mantra of the young writer “out there”; to recall my meatless days in heatless garrets in Chicago (while my wife was, of course, pulling down a handsome living for us), of dashes down to the mailbox, of envelopes ripped open, form rejections hungrily scoured for encouraging nuances in phrasing, or the slapdash “Pls try us again” appended by some work-study math grad student with a heart of gold, who at two a.m. and deep into reefer, begins to “feel for me” far away in the Windy City doing God’s work unheralded and alone — and how all that made me work harder and get better while staying humble and uncynical. It wouldn’t even be true. Moreover, it would be cloying and insulting to anyone actually trying to do God’s work. Sad life stories, even pathetically sad life stories played for jokes, never offer much comfort to the truly serious.

Still another introduction topic might be the simultaneously-thriving-yet-still-somehow-beleaguered university writing program industry. Perhaps now would be the time and here the place to give it a good flagellating, put on my jeweler’s loupe and scope out its flaws and corruptions. The French, after all, think we’re a bunch of sillies for trying to “teach” writing. They, of course, think the way they do everything is the best way, and that becoming a writer is a gnostic, quasi-Zen, for-mandarins-only process that mustn’t be spoken of in public — whereas we Americans will talk about anything forever. But who cares what the French think? They’re not satisfied with their own writers, either. Though plenty of American pseudo-mandarins natter on about this subject, too — usually toward the point that altogether too much writing’s going on, that there’re scandalously more writers than readers, that the writing gene pool is somehow being diluted and the world flooded with mediocrity, that the real writers don’t

teach, that editors are going brain-dead, on and on and on and on

again. But unless I’m wrong, Tennessee Williams and Flannery O’Connor both went to Iowa. Barry Hannah went to Arkansas. Ken Kesey and Robert Stone attended Stanford. And as a group, these satisfy my requirements for being wonderful writers, their books wonderful books. What difference does it make where you learned what you learned, if you learned it well? If every holder of an M.F.A. isn’t quite as good as these people, what’s the harm, really? It seems like a victimless crime. Maybe they’ll all become better readers of other people’s good books. Plus, everybody has to be doing something, don’t they? Would we rather more people were out in California designing video games?

And I’m sure there are other topics worth introducing this volume with: the influence on the American short story of deconstruction and the critical works of Frank Lentricchia. Web sites and hypertext. The “market.” Venal agents. The “death” of first one thing and then another. But those introductions will have to wait for another day.

In compiling these eleven specimens, I have observed very few rules, only ones which I’ve hoped would benefit the random, unknown reader. Most of what’s here are actual short stories, though I’ve not excluded parts of longer works if the integrity of the writing overcame the absence of a more succinct and purposeful structure. Gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other such non-literary concerns have not mattered to the extent that I’m at all aware of them. Seriousness has not been enough, though funny stories would’ve needed to seem funny to

me. Experimentation has not been suppressed, nor has literary heritage (“my story was probably influenced by Proust”) been a selling point. I have not minded about why stories got written — reasons of personal therapy, self-expression, confession, risk-taking, insomnia, time to kill, the influence of Kenneth Patchen or David Foster Wallace — but I have demanded that the writing concedes in some detectable way that I — the reader — exist and am doing my best to get with the story’s program. To me, good writing manages at a very primary level to acknowledge that a reader is using his brain cells up as he reads, and needs from the writing to be rewarded. On the other hand, writing that seems indifferent to me and my lost brain cells invites indifference in return.

Finally, though I may be growing soft and patient with age, I liked the reading I did during these months. I did all my

Ploughshares reading in Paris, and maybe I imagined I actually

was related to my “uncle” Ford Madox Ford-fifty-ish, feeling under-appreciated, mouth agape, editing, in that former Ford’s case,

The Transatlantic Review back in 1923: a “halfway house,” he called himself, “between non-publishable youth and real money.” A repeated feeling I’ve earned from my few years of writing stories is that I do precious little for anybody else — this, though my intention is avowedly other. And yet as I believe that what good writing mostly needs is a willing audience, I have simply tried during the last half year to make myself useful by hopefully and enthusiastically offering myself.