Introduction

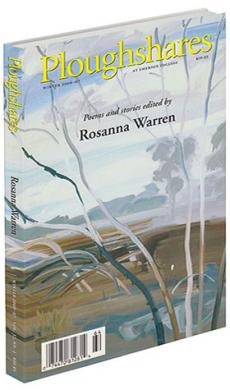

"World is suddener than we fancy it," Louis MacNeice announced in his poem "Snow": "World is crazier and more of it than we think, / Incorrigibly plural . . ." So I felt, collecting the poems and stories for this issue of Ploughshares. The issue was like the great bay window in MacNeice’s poem, with the writings as surprising, as "collateral and incompatible," as the snow and pink roses in "Snow."

The pieces I looked for dislocate ordinary language and ordinary vision, and relocate them in parables of sudden insight. The poems suggest stories while casting their song-spells; the stories tilt sentences and paragraphs into rhythmical sequences that formalize the words with which we think we are familiar from everyday speech, explanation, narration, excuse, prayer, and curse. I looked for work that would floodlight the true oddness of life in the crafted oddness of language.

A journal is a collective. That fact is both moving and revelatory. Writers work alone, but they work also in the light of centuries of the art that preceded them and gave them the forms in which they make their discoveries. And they work in the light—or is it the half-light?—cast by their contemporaries. An issue of a journal pitches a camp on a long caravan route. It is a provisional way station, and in the somewhat happenstance companionships and contiguities found there, one perceives a momentary pattern in the larger imaginative trade routes of a period.

The sense of the world as "suddener" and of art as, in part, collective teaches humility. Literature is ancient, and life’s purposes outpace us: we are granted our glimpses.

Love has its triumph and death has one,

in time and the time beyond us.

We have none.

Only the sinking of stars. Silence and reflection.

Yet the song beyond the dust

will overcome our own.

So wrote Ingeborg Bachmann in "Songs in Flight" in Peter Filkins’s lovely translation. Each true work has that humility, yet echoes, too, the song beyond the dust. That is what I listened for in the poems and stories gathered here.

A note of triumph, also, sounds in a work of art well made. It has found a small order that will suffice until the next stab of vision, the next destruction. For it all must be begun again, over and over. In that perpetual beginning lies our hope, our private warrant against the world’s insanities. The French poet René Char, deeply and responsibly engaged in military resistance to the Nazi occupation of France, composed two books of poems while he was hiding out with his men and fighting from the maquis. These books, Seuls demeurent and Feuillets d’Hypnos, were published only after the conclusion of the war in the volume Fureur et mystère. From his poem "Jeunesse" (Youth) I take one of the lines by which I live, and under whose protection I would like to place this issue of Ploughshares: "Le chant finit l’exil." Song puts an end to exile. Without such faith, why would we write?

And yet there are writers, rare ones, who work from a principled faithlessness, and so the question "why" is substantial and fertile, not rhetorical. A collection of poems and stories should provoke that real question, and leave the work of answering to go on in the mind of the reader. Whose every answer will be tested by the next poem, the next story. To keep us from sleepwalking. To keep us alive to one another.