Introduction

My sophomore year of college, I had a job in the cafeteria dish room: scraping food off plates, stacking trays, helping the occasional panicked freshman dig through trash for a lost retainer. At the end of fall semester, I got an unexpected call from the financial aid office. The college’s professional literary magazine was looking for a work-study student, and some guardian angel in the English department had recommended me. I’ve never said yes faster.

I worked for that journal (the lovely Shenandoah—then a physical magazine, now online) for the next two and a half years and received a literary education entirely separate from my actual degree. Much of what I did in the office was open mail: mountains of paper, in what we now know were the last days of snail mail submissions and SASEs, of wonky staples and errant cover letters and coffee-stained poems making their fifth hopeful trip around the country. I would take those same self-addressed envelopes, a month or two later, and stuff them with rejection slips. Hundreds and hundreds of rejections slips—an eye-opening sight for a ninteen-year-old aspiring writer. And four times a year, I’d fill a handful of those envelopes with acceptance letters and contracts. I imagined, as I slid each small stack in, that I could hear the whoop of joy that would greet these papers on the other end.

In the basement of the building that housed the offices of the jouranl were two things: many boxes of trophies that the athletic department had abandoned there in the mid-seventies, and metal shelves full of the journals that traded free subscriptions with Shenandoah. I had never heard of them before, but I soon knew their names and looks intimately: the Kenyon Review and the Paris Review and Prairie Schooner and Ploughshares and the late Glimmer Train. First, I was in charge of alphabetizing a previously chaotic mess, from AGNI to Zyzzyva, and then it was my job to bring new issues down as they arrived, to wrestle them into tight slots. I discovered that some journals were lush and illustrated, with soft paper. Others hadn’t changed their simple but iconic design in decades. There was a journal for which each issue was a different size and shape, which must have sounded like a great idea at the time. When I stole time to read, I found that some were experimental and some regional and one accepted only sonnets. For many of these journals, we only had a few issues; for others we had dozens of volumes, some older than those trophies. There were issues of Poetry magazine dating back to the 1950s.

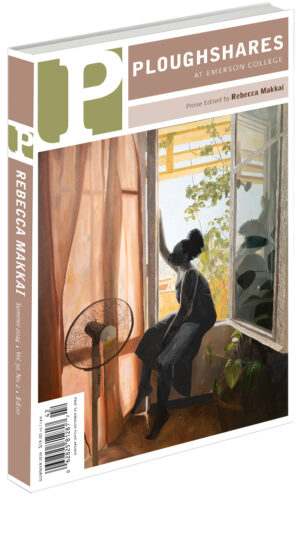

The world of journals became the literary landscape for me. I didn’t dream of publishing a novel or giving a reading in New York but of getting one of those little bios in the back of Ploughshares. It was partly that I’d grown to admire the magazines themselves, of course, but also that in opening all those envelopes, removing all those staples (the editor could not abide staples), carefully refolding those rejected poems and sending them home, I’d come to feel like part of a dissipated community of literary souls, ones who sent their stories out into the wind again and again, hoping they’d find somewhere to land and someone to love them.

I was deeply honored to edit this issue of Ploughshares, to discover voices new to me and to commission work from writers I’ve admired for years. And I loved working with these writers to fine-tune already brilliant pieces. I hated turning down work I admired, work that deserves an audience. It turns out that it’s a lot easier to stuff rejection slips into envelopes than to be the one making that call.

If some student comes across this issue in a dank basement or a digital archive a hundred years from now … well, I hope you’ll understand it right away, because I hope this journal and a thousand others are still thriving. But in case this part of the literary landscape has vanished with the coastlines, please know: This is how we loved our brutal world. We told stories about ourselves, about others, about our fragile planet and fragile hearts, and—in the purest expression of faith and hope that I can imagine—we sent them out to find their homes.