Introduction: Death in Hollywood

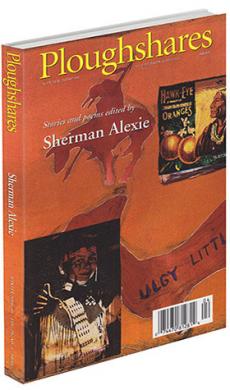

For the first time in my life, I had writer’s block. This writer’s block was so bad, so pervasive, so debilitating and humiliating (and so pretentiously stereotypical) that I couldn’t write anything. Or perhaps, more accurately stated, I couldn’t write anything with any sort of confidence. The words still filled up the page, but I had lost the ability to tell the good from the bad. (Some might argue I never possessed that ability!) More importantly, I’d lost the courage to ignore the opinions of others. I’d lost confidence in my individual voice and vision. This was true of my poems, stories, essays, novels, and screenplays. I turned down a few lucrative offers to write journalism for magazines and newspapers I admire because I knew I wouldn’t be able to finish the assignments. I missed all sorts of deadlines (like for this

Ploughshares introduction, contradicting all the flattering stuff in Lynn Cline’s profile about my effortless work habits) and offered pitiful excuses for my lack of production, none of which came close to the truth, and the truth was this: I was afraid. I was in a personal and professional nightmare and often wondered if I’d ever find my way out. In fact, as I write this, I’m

still in the middle of the nightmare. I’m only writing in the past tense out of desperation and hope.

So, why all the drama? My problems began with my work in the movie business. It’s a sad old story. Too many novelists and playwrights have gone to Hollywood and tried to strike it rich, only to be met with crushing disappointment. Hollywood broke Odets right in half, mutilated Faulkner’s spirit, and made Fitzgerald feel like a second-rater. I’m certainly not in those guys’ literary league, so if they could be treated like second-class artists, then Hollywood would certainly have no problem beating the shit out of me. Of course, those beatings are rarely inflicted out of disdain, hatred, or condescension. My writing and I have mostly been received with grace and courtesy by the movie business. Jesus, I’ve been paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to work on screenplays I’m quite positive will never be made into movies, so that’s obviously a very sure and strange sign of appreciation. And yes, I’ve met with my share of megalomaniac monsters (mostly directors), capitalistic lowbrows (mostly studio

executives), and outright crazies (a broad category of folks), but most of the people in the movie business are decent and hardworking people.

So why am I bitter? Well, I’m bitter because screenplays are written by committee. To be sure, filmmaking is a collaborative art form (don’t let any megalomaniac director or French film critic or Francophile American film critic tell you different), but the writing itself should never be collaborative. At least, that’s my opinion. Or at the very least, it’s how I work and cannot work with others. For those of you who don’t know, this is how screenwriting functions in Hollywood: A writer works for weeks or months, turns in a draft of a screenplay, then waits for weeks or months to receive comments (Hollywood calls them “notes”) from directors, producers, actors, agents, managers, and a cast of thousands, then the screenwriter is supposed to respond to those notes and rewrite the screenplay accordingly. This process might sound simple, but it is exceedingly torturous. For me, it’s torturous because I can never write one word, not even a pronoun or preposition, with the confidence that it will not be

changed. I hear “their” voices in my head whenever I sit at my desk to work on a screenplay. I hear “their” voices in my head whenever I sit in a theater to watch a movie. I hear “their” voices whenever I think about movies or movie-making. And “their” voices always say the same things, all of which can be distilled into the chorus for a song I wrote:

We think you’re brilliant, we think you’re brilliant.

We think you’re brilliant, we think you’re brilliant.

Now, could you change just this one little thing?

If you work full-time as a screenwriter in the movie business, I’m sure there’s a way to successfully negotiate the notes meetings — hundreds have to do it every day — but I’m also quite sure the process chips away at the walls of your artistic soul. After all, I’ve never received a note wondering if I could somehow make the screenplay a little more “difficult,” or that I might want to add a few more literary allusions “in order to give the work intellectual depth,” or that I should include more dialogue, because “frankly, these characters are intelligent and highly educated, so I think we should take advantage of that.” Instead, the notes always, always, always have something to do with making the screenplay more “accessible.”

That’s a poisonous word for me, a public-school-educated, Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Indian boy who grew up on a reservation in Eastern Washington State in the Pacific Northwest. You see, all of those educational, racial, cultural, and geographical distinctions make me the unique, eccentric, iconoclastic, and inaccessible individual that I am. But every one of those distinctions also marginalizes me in some fundamental way. I’ve always lived my life and written my books outside of the power structure. In order to be accessible, I’d have to work within the power structure. And yes, while writing screenplays, I have been working within that power structure, right in the damn middle of that power structure. And yes, the contradiction is killing me. Yes, this is my brain, a cute little egg, and this is my brain on screenplays, an egg sizzling in a frying pan with ten hypodermic needles, six vials of crack, and a copy of Syd Field’s

Screenplay.

So what does this have to do with my writer’s block? Well, I’ve started to hear “their” voices, those Hollywood voices, whenever I try to write

anything. I’ve even begun to wonder how I should change this introduction in order to make it more accessible. I worry if I should add more drama in the first paragraph and a few more punch lines in the third paragraph. I wonder which actor will play me when I adapt this introduction for the NBC miniseries. Of course, I’m exaggerating here, but that’s only because I’m again afraid to tell you what’s really happening to me and my work, and what’s happening and what’s going to happen is this: If I don’t get out of Hollywood, I’m going to lose what got me here in the first place — my love of writing.

So, near the end, here’s the thesis of this damn thing: I’m quitting Hollywood. I have to finish out a few contractual obligations, but I’m not going to write screenplays for them anymore. I’m still going to make movies, but I’m going to make them in the same way that I write books: all by myself, with all my inaccessible bullshit, all of my good and bad writing, and most of the soul I have left intact. I’m going to make very cheap movies on video, and manufacture and distribute the videos all by myself, free from as many corporate influences as possible. I’ll make movies like I write poems, knowing full well that 99.9% of the world couldn’t care less, but equally aware that a tiny little 0.1% of the world needs and loves poetry.

So, there you go, I want to be a writer, like all the wonderfully talented women and men in this issue of

Ploughshares, all of us doing our best, all of us crazy and courageous enough to think that poems and stories matter more than just about everything else.