An Invitation to My Demented Uncle

It's never been so bad; it's rarely been so good: an assessment of the current state of American poetry. The bad side: circumstances, some economic, some not. Many major book-review and critical journals have almost entirely ceased reviewing books of poetry-at least, poetry by living writers working in English. One rationale given: there are so many published, it's impossible to tell the good from the bad, what's "important" from what's not. Critics who read poetry, I respectfully submit, can tell-even if they disagree. Imagine that reasoning used as an excuse for not reviewing novels! Poetry is "the demented uncle at the dinner table, dribbling into his napkin," said a participant at a recent PEN symposium on book reviewing; someone else said, more or less, we don't give poetry review space because it doesn't sell. That old self-fulfilling prophecy!

Who, I wonder, buys those S45 biographies and books of literary theory which are reviewed and do, presumably, sell? (A biography of a poet, even a living one, will receive more critical attention than the poet's newly published work.) Libraries buy them, for one-libraries which used to be responsible for purchasing, I'd guess, three-quarters of the print run of any new hardcover poetry collection. Looked at the 800 shelves lately? We know how library budgets have been slashed, library hours and personnel pared to the bone: a percentage of the diminished library funds remaining are now earmarked for the purchase of videocassettes. But the absence of reviews and criticism of new books of poetry exacerbates the situation: a librarian can't order a book s/he doesn't know exists, is unlikely to order a book only glimpsed in a catalogue. That's true of booksellers as well, who, today, must do aggressive research to keep a well-stocked poetry section. Then there's the price of the books.

A 96-page poetry trade paperback might have cost $3.95 in 1977. Has your disposable book-buying income doubled-or tripled-since then? Has that of the average graduate student?

If poetry was ever in danger of being marginalized as "elite" literature, it's now in danger of being marginalized out of "literature" altogether. If contemporary poetry is not reviewed, not easily available in libraries, not found in many bookshops, priced by the ounce like caviar, where and how will it continue to exist for readers? Where will new readers discover or be introduced to it?

Paradoxically, in this reader/writer's opinion, American poetry has never been better. There's a lot of mediocre work published, for sure-but 99% of everything published, in any genre, is mediocre. It's the breadth of the mediocre that allows the exceptional to emerge. It would be impossible for even the most conservative critic (if even the most conservative critic could find page-space, outside of poetry journals, for the topic) to reduce the number of women poets, black poets, Native American or Asian-American poets, Hispanic poets, gay or lesbian poets, Southern or Northwestern poets, Jewish or Roman Catholic poets, to one exemplar each, who must typify and represent a kind of experience reflected in a mode of writing. No writer has to be

the black laureate,

the feminist bard,

the nisei chronicler or Sappho of the South Bronx. Freed from the necessity of being emblematic or exemplary, poets can (if they wish) write from any or many of those matrices, but be, if not

Alone With America (

pace Richard Howard), alone with American, their language, their toolbox and sewing basket.

There

are critics who claim that there is only one American poetry, or only one authentic one, or only one ground-breaking one: that may be L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E poetry, New Formalism or projective verse; obeisance may have to be paid to Whitman, Williams, Eliot, or Stein. I'm interested in all those poetries, and insist on my right to read and enjoy Rachel Blau DuPlessis

and Cheryl Clarke

and Carolyn Lau

and Molly Peocock (none of whom, alas, are in this collection). When I step outside the field of American poetry, compare it with a poetic tradition where intertextuality is taken at face value and poetry is assumed to refer to nothing but. . . other poems, I can instantly see as much in common as at odds in the work, say, of Audre Lorde and of Henry Taylor: the evocation of place, the involvement in narrative as an entrance in history, the depiction of character, the tension between demotic and elevated language, the fabulist's courage to draw conclusions.

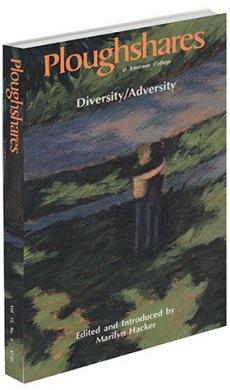

This issue of

Ploughshares, then, is meant as a tribute to the diversity of American poetic voices-indeed, of poetic voices in English, even though only one contributor, Eavan Boland, is not American (the "plus" part of what I've stated holds true for the rich current poetry of her Ireland as well). Some of the work here was solicited from poets already known to me: some appeared in the mail with unfamiliar return addresses: the real work and the treasure trove of editors. I had no theme and no literary manifesto in mind: only my own tastes and preferences. The fact that these were being sent to me, not another editor, surely self-selected some of the senders, and the texts they chose to send. It's because the pages that follow are so very much

not all of a piece that I think it's worth recording what I did note about them.

Should an editor discuss demographics? I'm pleased to see 17 states and one other country on the contributors' mailing labels. I'm more pleased to know that at least eight of these poets are over 60, and, of those, as many could be called "emergent" or "mid-career" as "elder statesmen or -women." More writers, especially women writers, are discovering late vocations, or finding the time and courage to pursue earlier ones later on: this despite the first-book prizes and literary awards that define a "new" poet, or even a "mid-career" poet, as under 40 or under 35.

Fifteen years ago, of the unsolicited submissions to a "general" literary magazine, 80% would have been from men; 99.9% would have been from Caucasians. The first statistic has changed dramatically enough that it's no longer unusual for a journal without a stated feminist stance to have half or more women contributors to a given issue. The second still requires active work, by white editors as well as editors/writers of color: it's the only way to know and show the real range of American literary achievement.

What is in our experience can enter the canon. This is part of an American populist heritage that stubbornly refuses a disjunction between art and life: domestic, sexual, economic and political life. As many poets here look out as they do look in. The response to AIDS threads this collection like a leitmotif (like the stitches joining pieces of a quilt). The disease is named by some poets (Dixon, Martin); the face of the plague is glimpsed in the work of others (Barrington, Bond, Gunn, Replansky, Santek). Many of the poets here are archaeologists of childhood. What is excavated from the real or fictive memory is sometimes the still-sharp blade of sexual or emotional abuse (Derricotte, Powell, Smukler), sometimes the point of intersection between the private and the public historical/economic world (Goldbarth, Moss, Pigno). Poets create their known or unknown parents and forebears as personae (Levi, Pigno, Troupe, Waniek), as conscious of the invention in the process as those who create the voices of

fictional or historical speakers (Cooper, Gardinier, Pitchford, Traxler). Parenthood as well as childhood is an interaction between the public and the private life: a subject claimed and desentimentalized by a generation of feminist writers, it is forcefully represented here in the work of Pratt and Seaton. Through all this, the exploration of the erotic, as epiphany and taboo, as private and as social ritual, is carried on by men and women of all persuasions (Fay, Gardinier, Harjo, Heard, Komunyakaa, Pitchford).

These writers often choose a narrative mode, as if the personal lyric could not contain their width and depth: even when the first-person-singular and present tense emblematic of the American lyric are used, there are frequent cues that this "I" is not to be conflated with "the poet"; that this "now" is not the moment of composition of the poem: that a story is being told, a character developed, a situation illuminated.

"Received forms" are alive and well, and used by poets of a wide range of ages, backgrounds, dictions, and aesthetic aims. If there is such a thing as a New Formalist, s/he may be a black activist as well. The prose poem, the long-breathed line of Whitman and Rukeyser, are forms American poets have received along with the sonnet and the syllabic stanza: they are all here.

We gain something by acknowledging, welcoming, the "demented uncle" (and eccentric aunt) in poetry, the irreplaceable holy-fool aspect of Blake, Smart, Whitman, Dickinson, Moore, Pound, Berryman, Ginsberg. But the best poetry, whether written by nuns, vagabonds or diplomats, is as profoundly sane as it is daring; the literary dinner table to which it is invited is graced by wit, wisdom, amazing stories, insights and shoptalk, and return invitations to places and occasions not easily reached otherwise.