Mercy

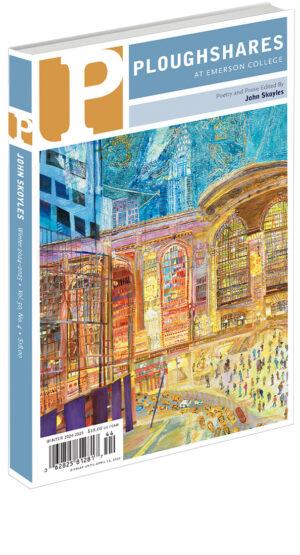

Issue #162

Winter 2024-25

What they did to Eddie the night he overdosed was put tubes up his nose and needles in both arms and then roll him into a room in the hospital where machines made dull roaring noises, and he had to...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.