My Refugee

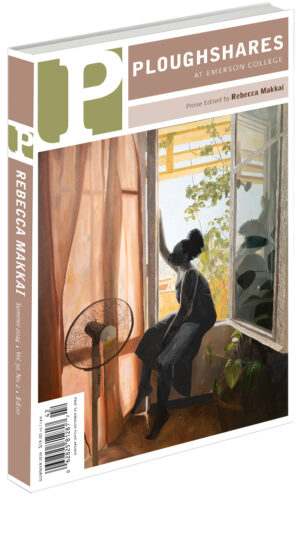

Issue #160

Summer 2024

It is five in the morning in the worst of winter, and I wake up to a knock on the door (we bought the house last year, when everyone who could buy a house was buying a house, and were...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.