Ponies Gathering in the Dark

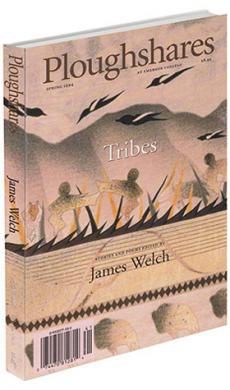

Issue #63

Spring 1994

The house was a forest remembering itself. The pine trees that held up the walls dreamed of stars dwelling in their needles. Jointed, branched, rooted, the trees still listened to the wind. The oak floors gleamed from the generations of...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.