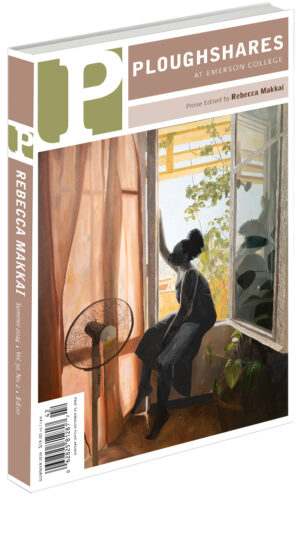

Prolific Donor

Issue #160

Summer 2024

My brother—ever emotive, ever sentimental—did one of those 23andMe tests, which I had advised against, but that’s Harlan. Harlan and I are twins, extremely NOT identical—and were supposedly the product of donated sperm, plus a donated egg, which were combined and gestated...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.