rev. of All-American Girl by Robin Becker

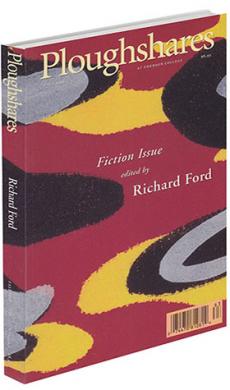

All-American Girl

Poems by Robin Becker. Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, $10.95 paper. Reviewed by Joyce Peseroff.

Gathered at the edge of each poem in Robin Becker’s moving fourth collection, palpable and terrible, wait the forces of chaos. Love affairs end, families dissolve, the kingdoms of childhood are lost.

All-American Girl, despite its insouciant title, is a sad book recounting a life fully adult and aware of human limits. Becker documents a struggle for order and sense in a universeas disordered as the one at the end of “The Star Show,” whose out-of-control planetarium commentator “[throws] stars across the sky, [flings] meteors / carelessly . . . / . . . punctur[ing] the darkness with white bullets.”

Two events inform and shape the book: the death of the poet’s sister, and the breakup of a long-term relationship. Becker is aware of how slight individual loss weighs against the heft of landscape and history. In “Solar,” she writes, “The desert is butch . . . / / . . . her rain remakes the world, / while your emotional life is run-off from a tin roof.” As a lesbian and a Jew, Becker claims a history of expulsion and isolation. What is astonishing in these poems is how the author uses irony and humor — abundant in imagery as well as in tone — to define rather than distance herself from such knowledge. Becker’s inherently Jewish jokes can be self-deprecating and skeptical; imagining that a bird seen during her morning jog is really her grandmother “back to remind me / to learn Yiddish, the only international language,” she gets not transcendence but back-talk as the bird “flies / out of sight, shouting,

Big talker! Don’t run on busy streets!“In poems like this, we encounter the poet’s soul as completely as we do Wordsworth’s in his

Prelude.

Becker is alert to the play of political, familial, and sexual forces that bind intimate relationships. “Shopping” begins, “If things don’t work out / I’ll buy the belt / with the fashionable silver buckle,” both mocking and acknowledging the way women use clothing to control and define. The poem ends, “I’ll do what my mother did / after she buried my sister: / outfitted herself in an elegant suit / for the rest of her life.” In what may be the book’s most powerful poem, “Haircut on Via di Mezzo” reverses the Biblical story of Samson: in place of the hero shorn by a seductive woman, a little girl weeps at the loss of her floor-length hair, fixing “her gaze on her father. / Cool and serene, he nodded to her, . . . / and she, obedient . . . leaned / toward the blades and turned her wildness inside.” As Becker writes in “Santo Domingo Feast Day,” “there are no remedies for great sorrow / / only dancing and chanting, listening and waiting.” And, I might add, reading poems of wisdom and consolation such as

those found in

All-American Girl.

Joyce Peseroff is the author, most recently, of A Dog in the Lifeboat,

a collection of poems from Carnegie Mellon University Press.