rev. of Cheaters and Other Stories by Dean Albarelli

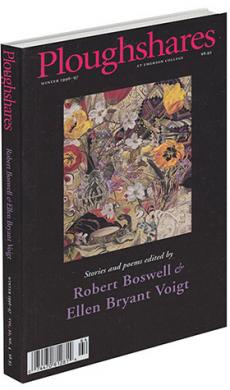

Cheaters and Other Stories

Stories by Dean Albarelli. St. Martin’s, $20.95 cloth. Reviewed by Joan Wickersham.

Dean Albarelli’s

Cheaters and Other Stories is a collection about moral responsibility, as considered by people who have, for the most part, disappointed themselves. “What he needed was the energy and idealism of his younger self, back when he was so damn sure he’d be a flawless husband and father,” one character thinks ruefully. Another flirts with the possibility of an affair that would betray his longtime girlfriend, even though he can already predict his own disillusionment: “Then again, wasn’t this only the novelty of someone new? A novelty that will no doubt wear off in time, given the chance. And what would he be left with then?”

What distinguishes these from other tales of emotional fatigue is their crisp, often comic specificity: these are stories about weariness written with tremendous energy. A character drifting toward adultery with an older woman picks up her feet and notices she has very long toes. He fits his fingers between them. “I’m holding hands with your feet, Margaret.” The silly irreverence of this, and the complexity — it’s partly affectionate, partly cruel, and partly just weird — juxtapose memorably with the weight of the character’s guilt and confusion.

Albarelli’s energy in this first collection is also apparent in the admirable range of the stories. In one, he writes in the guise of a twenty-nine-year-old female book designer, who is ambivalent about her own Jewishness and alternately irritated by, ashamed of, and deeply tied to her Orthodox twin brother. In another, the storyteller is a father, acutely aware of how flawed he looks in the eyes of his beloved, mercilessly secure sixteen-year-old son. And there’s a story written from the viewpoint of a disillusioned, drugged-out journalist whose adventures spin along in a bizarre series of causes and effects with the unreal, inevitable quality of a dream.

This variety is more than mere virtuosity; Albarelli is a patient writer who fully explores the consequences of each of his choices, never hastening a story to a conclusion. In most of these pieces, it is not the language that is embellished, it is the world of the story itself; every revealed detail implies many more that the writer has chosen not to include, and the fact that he knows so much more than he tells gives each story a satisfying heft.

In the stunning, understated “Honeymoon,” for example, Albarelli tells the entire story of Shane, an IRA terrorist, from idealistic commitment to ruthless skill to disillusioned horror, without actually narrating any of the formative events. In fact, the drama of the IRA is downplayed; Shane compares his loss of purpose with his feelings about the university track team: “Somehow it has always been that way with me; just when I become quite serious about something, or committed to it, or proficient at it, I lose interest in the thing.” The story’s only violent image is one that haunts Shane’s dreams: that of a young woman killed by a bomb, whose half-naked body he has seen lying beside a bathtub in a supposedly “safe house.” This image is implicitly recalled on his wedding night, when his bride, a virgin, is frightened and baffled by her own pain: ” ‘Shane, we’re after doing something wrong; I’m bleeding.’ ” And we are left gazing into the unbridgeable gulf between her utter innocence, and his utter

lack of it.

Joan Wickersham’s fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, The Hudson Review, Story,

and Best American Short Stories.

Her first novel, The Paper Anniversary,

was recently issued in paperback by Washington Square Press.